TV or Not TV | Neutrality is Not an Option: Raoul Peck’s Exterminate All the Brutes

By Robert Koehler

In the fourth and final episode of Exterminate All the Brutes, Raoul Peck declares in his commanding voiceover narration, “The very existence of this film is a miracle.” Those are mighty big words for a filmmaker to say about his own work—it’s hard to imagine even the always self-impressed Godard making such a statement—but by the end of Peck’s grand yet accessible essay film, the viewer can’t argue. Given the existing media power structure, given the odds against funding a three-years-in-the-making project about the history of white genocide against Indigenous and non-white populations across the world (and, even more fraught for fundraising challenges, with a particular critique of the US’ genocidal policies), and given the current political climate…well, yes, for Peck to be able to make this, and then have it broadcast by HBO and supported by a lavish marketing and publicity campaign, calling this “a miracle” might be a modest claim.

Peck has said that his previous nonfiction film, I Am Not Your Negro (2016), based on James Baldwin’s unparalleled work exploring the sources and consequences of racism in the US, was meant to be his definitive statement on this issue. He found, though, that the reaction to the film in Europe tended to view structural racism as an American problem, ignoring its legacy in European history. This demanded some kind of remedy. He also noted that Richard Plepler, then-chairman of HBO, was so distressed that Peck hadn’t approached the network about I Am Not Your Negro that he offered him carte blanche on his next project.

The next Peck project turned out to be an international co-production not involving HBO, the wan biopic The Young Karl Marx (2017), an unusual addition to Marxiana (it was the first movie with Marx as the central character) that exposes Peck’s flaws as a dramatic filmmaker. He’s prone to a Stanley Krameresque reflex when dramatizing actual events, a rote approach in which the drama reveals every bit of the research—a Left equivalent of Disneyland’s animatronic Presidential robots. When he fights these tendencies, however, he can create some fascinating character studies, as in his best drama, Lumumba (2000).

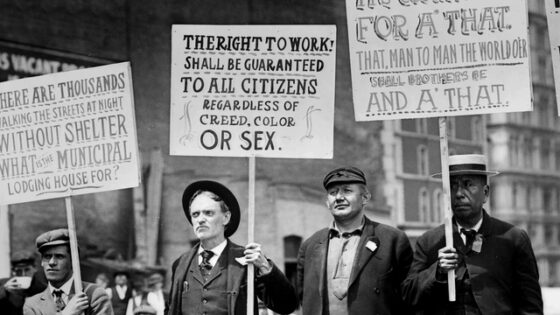

The Young Karl Marx is a mere sideshow for Exterminate All the Brutes, which is certain to be remembered as Peck’s magnum opus and one of this era’s key essay films. It doesn’t hurt that Trump was in the White House during its making: an incandescent anger fuels the film and is essential to its power, but it never clouds Peck’s judgment of his topics, themes, and artistic selection. To be clear, Brutes is not, as has been argued elsewhere, anywhere near the zone of Chris Marker’s internationalist essays such as Sans soleil (1983), which is an act of mindfulness meditation by comparison to Peck’s polemic. Brutes has also been labelled, in presumably negative terms, as “strident.” In this way, Guernica depicting Franco’s aerial obliteration of a Spanish town or Diego Rivera’s murals capturing corporate suppression of organized workers may be similarly labelled—and this would be quite beside the point. The only shock of a four-hour study of centuries of deliberate genocide would be if it lacked a measure of strident rage.

Instead, the most impressive quality running through the film is how it keeps its cool. Some of this comes from Peck himself, some from his collaborators. Peck’s declarative narrating voice hits a deep register, as if rubbed with sandpaper. This instantly personalizes the film, lending it an intimate, musical feel (I kept thinking of Charles Lloyd’s flowing yet charged sound on sax), and also allows Peck to organically inject his life story. Growing up in Haiti, moving with his parents in 1961 to the newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo, living in the US, studying cinema in Berlin, and working in Paris, Peck is a global citizen in the truest sense. He includes many family movie clips and school photos in the film, such as one from his 1962 class.

That same year also saw the premiere of the movie that can arguably be viewed as the swan song of Classical Hollywood. Though Peck selects John Wayne’s even more bloated (and strident!) The Alamo (1960) as his example of how movies made in the triumphant, conquering nation-state retold history from the conqueror’s point of view, it was How the West Was Won (the title itself says it all) that best exemplifies one of his key arguments, borrowed from Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s book Silencing the Past: Hollywood, through its powerful grip on the collective imagination, controlled the dominant narrative of global winners and losers, meaning that (citing Trouillot) “whomever wins gets to frame history.” The Alamo rewrote history as a win for white Texas rebels against Santa Ana’s actually victorious Mexican army, but How the West Was Won goes much further and is even more flagrantly imperialist, telling the victor’s story of how white intruders won in a decades-long battle for supremacy of the land, delivered by a titanic cast of many of the legends of MGM and other studios, including Wayne (of course), Debbie Reynolds, Gregory Peck, Karl Malden, James Stewart, Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, Agnes Moorehead, Walter Brennan, Richard Widmark…and on and on, a living museum as the curtain closed on Classical Hollywood.

I’d like to ask Peck (Raoul, that is) if, as I did, he experienced how Hollywood changed its tune as he was growing up from grade school to middle school in the ’60s. Less than eight years after How the West Was Won, 1970 (when he was 16 turning 17) marked the arrival of three movies that depicted US white expansion from a First Nations point of view and/or dramatized the Indigenous population’s extermination by white invaders: Soldier Blue, A Man Called Horse, and Little Big Man. A young moviegoer at the time couldn’t help but notice the stunning turnabout in the dominant storyline of American conquest, what Peck terms “the doctrine of discovery” that resulted in “demographic catastrophe”: 90% of North America’s Indigenous population was wiped out in 100 years. Despite this striking reversal, no American movie has ever matched the broad perspective of the second of three books that provide Peck with his primary material: Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s seminal An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, which extends the historical project of Howard Zinn’s The Peoples’ History of the United States to chronicle US history from the vantage point of the exterminated.

Peck’s central collaborator, however, is his late friend, Swedish author Sven Lindqvist, whose 1992 book provided the director with both his film’s title and a thematic and evidentiary foundation without which the new film would be impossible. With Lindqvist as his guide, Peck creates a multimedia extravaganza, utilizing some astonishing animated sequences mapping historical/global routes of the slave trade, resource exploitation, and immigration patterns; graphic rosters of documented genocides preceding the Nazi Holocaust; elaborately staged dramatizations that are generally free of Peck’s weakness for on-the-nose dialogue and often feature a genocidal Everyman played by a silent, swarthy Josh Hartnett (who met Peck during an aborted project and has remained friends with the director for 20 years); a vast archive of film clips; and, most notably, a powerful rotoscoping technique in which Peck zooms in slowly on Indigenous and non-white figures in photos staring directly, Kubrick-like, into the camera. Where Ken Burns employs this technique as a gentle, illustrative form of storytelling, in Peck’s hands it makes the photos directly challenge—even accuse—the viewer, forcing our eyes to pay attention to what the “winning” culture wants ignored.

Aesthetically and even spiritually, Peck’s approach is anti-auteurist: he generously credits Lindqvist, Trouillot, and Dunbar-Ortiz, particularly Lindqvist’s probing account of the rise of the intellectual defense of white supremacist genocide. Lindqvist, in turn, was inspired in his book (which includes an account of a wild trek into far southern Algeria and the central Sahara) by Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, in which the seafaring narrator Marlow describes his venture into the Congo jungle to encounter the legendary, feared ivory trader Kurtz and his strange “kingdom.” It is in the footnotes of one of Kurtz’s texts (titled “Suppression of Savage Customs”) that Marlow finds his most disturbing note: “Exterminate all the brutes!” For Lindqvist, Conrad was one of the first Europeans to fathom the horrors that more than a century of colonial land grabs had produced, its world-historical levels of ethnic eradication. (Nothing in the film’s most violent material—including a nightmarish torture sequence starring Hartnett—matches the astonishing human nightmare described by Lindqvist of British whites invading Tasmania in the 1820s, with results that make the most frenzied zombie movie seem comparatively tame.)

By deploying the historians’ texts, Peck’s film accomplishes the difficult act of visualizing information that revolves around historical patterns, the global cross-currents of capitalist expansion, and the deliberate elimination of certain members of our species by others, from the European Crusades in the Middle East and the Spanish Inquisition’s subjugation of Jews to the Holocaust, invoked in a final image of a hypnotic, overhead tracking shot of Auschwitz. One might add how earlier feudalist systems of economy and land management established and refined methods of crude genocide and subjugation, but each of these ultra-violent episodes strengthened a culture of institutional violence against weaker, poorer groups. For example, the crowned heads of Europe preferred military men from Spain’s hyper-feudal Extremadura region as their conquistadores; in this region, a kill-or-be-killed brutalism—an ethic of a true European Wild West—dominated day-to-day life, which these men casually practiced in their trans-oceanic plunder and pillage. Peck builds his case by layers, but also by a mind-bending collage as he shifts back and forth from images of white nationalists marching in the US to Peck’s memories of the Congo to the 1836 destruction of Seminole communities in Florida (marking Hartnett’s startling first appearance).

Like Godard in his essay-film mode, Peck, blending his own thoughts and feelings with Lindqvist’s, states his case in aphorisms and declarative sentences which lend the film’s soundtrack as much political fervour as its visual design. They are, as they used to say, humdingers: “You steal humans. What kind of species are you?” “This kind.” (Hartnett then shoots a Seminole woman, played by one of the other recurring actors, Caisa Ankarsparre, in the head.) “Neutrality is not an option.” “The happiness of one cannot be based on the pain of all the others.” Peck describing his early schooling: “I was whipped on the first day of school. I learned not to be so trusting after that.” From Trouillot: “Our job is to deconstruct the silences of historical narrative, those narratives silenced from the dominant narrative.” “The art of killing at a distance became a European specialty.” “The determining factor in history was the willingness to exterminate whole peoples in order to have their land.”

This last one sums it up. The massive extractions of natural resources in the 19th century, preceded by the grotesque three-century enslavement of Africans for the US cotton trade (“quietly bankrolled,” Peck observes, by European interests), weren’t the key drivers of extermination. Little Europe, with its limited land mass, needed more of it, and the extermination process (first an act of pure, unbridled cruelty by the conquistadores, later justified by 19th-century intellectuals such as Herbert Spencer and Robert Knox using Darwin’s theory of natural selection for cynical purposes) was a horrific and precise strategy of removing a land’s current occupants by any means necessary.

Before the film’s fourth hour, Peck sets the basis for his final argument, a wallop to the gut of anyone who’s ever viewed the Holocaust as a historically unique event. Hitler studied the American “Indian Wars,” especially those campaigns waged by Gens. George Armstrong Custer and William Tecumseh Sherman. (It’s worth inserting here that it was German filmmaker Hans-Jürgen Syberberg who first brought to my attention the direct connection between Hitler and the mythology of white conquest of the American West in his “German Trilogy,” particularly Karl May [1974] and Our Hitler: A Film From Germany [1977]). The Germans were, in fact, late to the extermination free-for-all; long after the British, the Spanish, the French, the Belgians, the Americans, and others had perfected genocidal land usurpation, the Germans turned German Southwest Africa into a killing field, forcibly relocating and murdering over 100,000 Herrero and Namaqua people in the 20th century’s earliest genocide. Hitler followed this approach in his Lebensraum plans to replace Slavs and Jews with Teutonic Germans in Eastern Europe and Russia. In this, he was following a long historic trail established by earlier monsters, only with more advanced technological means.

Exterminate All the Brutes definitively demonstrates that if you tell history as a story developed one layer at a time and, simultaneously, as a kaleidoscope uniting past and present, your conclusive thoughts can comprise an ironclad logic. It would be easy to imagine a distortion of Peck’s essay, highlighting only the point that the Holocaust wasn’t an extraordinary event, to label the project as somehow anti-Semitic. This would be a bad-faith gambit by forces opposed to the entire project of, for example, restitution to Indigenous peoples and reparations for Blacks in the US—both of which Peck calls for in the most direct fashion I’ve ever heard on television or in cinema. These, of course, are the same purveyors of bad faith who placed a bust of Andrew Jackson, the original American “Indian killer,” in the Oval Office. Seldom has a film so steeped in righteous anger been delivered by a cool logic and on such a mass basis to an audience that, after the summer of George Floyd, has been so primed to absorb it.

Robert Koehler