Film/Art | Provenance: The Artist (Amie Siegel)

By Andréa Picard

When Heidegger assigned the virtue of truth to works of art, he did so while heeding to his own tastes as any aesthete would. The origin of a work of art, he opined, is where said authenticity lies. Determining provenance is thus imperative to understanding the essence of an artwork, which significantly contributes to the culture and community to which is it born. When a work of art is drained of its original purpose or dynamic status, it inevitably devolves into a passive state and becomes an object that “no longer offers resistance to rationalization.” Heidegger was prone to insightful, fascinating, and somewhat obfuscating contradiction, and his treatise “On the Origin of the Work of Art,” which grew out of a series of lectures given in Zurich and Frankfurt in the mid-’30s, is rife with divergent thought, ultimately sending us on a prescient quest to examine the objectification of art by way of a weary binary: modern spleen versus ancient ideals.

Admittedly, that’s a pretty abrupt and crude shortcut summary. Still, given the lines of thought that comprise Heidegger’s major contribution to Western aesthetics, it’s rather surprising he’s not more readily invoked in debates concerning immanence, provenance, and the art market run amok. Der Ursprung, Heidegger’s German word for “origin,” is the “springing forth” of a thing—a trajectory of nascence and beyond like the one speculatively documented and deftly mirrored in Provenance (2013), American artist-filmmaker Amie Siegel’s most recent and most ambitious multi-film project. Provenance traces in reverse the origins of furniture (chairs, desks, tables settees) designed by Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret as part of their holistic, utopian conception for the Indian city of Chandigarh, designated the modern capital for the states of Punjab and Haryana following India’s independence in 1947.

As if mysteriously enacting the provenance document of a work of art, Provenance traces its subject’s lineage via a beguiling immersion into the present tense, perpetually in situ. The film proceeds—both gracefully and glacially, with elegance and precision—like a grand, slow, monumental reveal; encountering the film blind (as I did when it was exhibited last October at Simon Preston Gallery in NY) significantly heightens the suspense, which is formally and stylistically inscribed in the film. Even with the inevitable spoilers induced by the film’s description and press, the experience of watching the film is mesmerizing, startling and troubling, even upon repeated viewing. Beginning in swish and disarmingly tranquil homes in London, Paris, Antwerp, Manhattan, and the Hamptons, where a certain haute minimalism and Architectural Digest aesthetic reigns, and alternating between static observational shots and smooth tracking ones, which glide through these spotless and seductive spaces, Provenance thrusts us into a private and privileged milieu which houses the silent protagonists. With a successive montage that, on the surface (and only the surface), recalls the metronomic rhythms and blinking point-of-views of Heinz Emigholz’s great architecture surveys, Provenance hones in not on the stunning views or architectonic details, but rather on the Corb and Jeanneret furniture, whose engraved imprimatur is revealed in close-up—the stamp of authenticity, the codes of origin.

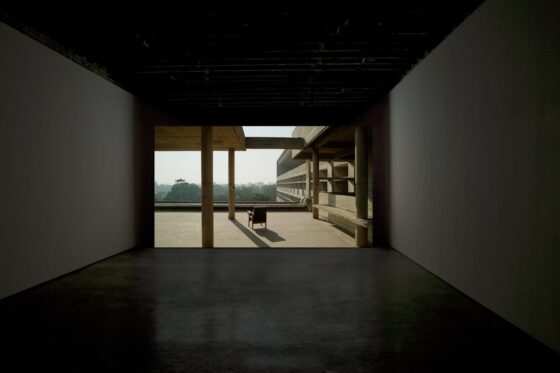

As the film follows—with a marked focus on the teak and leather (re-)upholstered chairs—the furniture’s backward geographic peregrinations and attendant shifts in worth, including a passage on a jaw-dropping mega-yacht replete with whooshing glass elevator, the magnitude and complexity of the high-end furniture and design trade is not simply explored or implicitly denounced, but an entire constellation of cultural and monetary consequence is gradually invoked. The film travels along the circuit that it investigates, documenting the furniture’s sale at auction (a spartan room in Chicago’s Wright auction house where a plethora of proxy bidders are mouth-whispering into the phone, and a bustling French preview), the primping, photographing, and cataloguing of the goods, the buffing and restoration process (frighteningly destructive), ultimately arriving in Chandigarh, where the dust-laden Corb furniture is piled high in discarded stacks, having been replaced by new, ergonomic office chairs more conducive to computer-based office work being conducted in the adapted Secretariat. The scenes in Chandigarth are some of the film’s most breathtaking, and include rarely seen views inside Le Corbusier and Jeanneret’s Brutalist mecca.

Shot with the same frontal rigour throughout, Provenance maintains a tone of distance, eschewing narration and interviews, as its trajectory, timeline, and performative self-reflexivity speak rather eloquently about cultural memory and heritage, worth, the transit and circuitry of art, the dominance of the market, fetish commodity, appropriation, ownership, and aura. Der Ursprung and a host of other complex issues that are made associatively clear though the project’s multi-element structure. Along with Circuit, a looping one-minute video comprised of a 360-degree panoramic tracking shot of the “Evolution of Life” exhibition in Chandigarh’s Corb-designed Natural History Museum, Proof (Christie’s 19 October, 2013), an inkjet print of a proof from Christie’s auction catalogue encased in Lucite, and Lot 248, a six-minute video documenting Provenance’s sale at auction (prefigured in the proof)—the final point of transit along the conveyor—Provenance is an enduring work of accumulation, and avowal. Its provenance: the artist (Amie Siegel).

Following Provenance’s inclusion in the Berlinale’s Forum Expanded section where it won the inaugural Think: Film Award, Amie Siegel generously spoke to us about the film, its place within her growing oeuvre, the speculative nature of the project, and the cultural assumptions that have, perhaps inevitably, escorted the project.

Cinema Scope: It may be in poor taste to begin by talking about money, but given Provenance’s subject matter, it seems rather apropos. The initial and most striking features about Provenance are its high production values, its aesthetic beauty, and its quiet monumentality. With its peripatetic and ocean-spanning journey, its breathtaking overhead establishing shots and razor-sharp precision, the film looks like it was expensive to make. It has the feel of an objet. Aside from wanting to make a formally beautiful film employing your signature tracking shots, are you commenting on aesthetic beauty and its place (i.e., market value) in the world through the film’s style? Or is it a play on cinematic tropes and genre grammar to invoke the complex nature of its subject?

Amie Siegel: Provenance deploys images that mirror the work’s purported subject, the design objects that travel from one value context to another. Many of the spaces filmed, for example, the collectors’ homes in Paris, Antwerp, London, the Hamptons, even the auction preview exhibitions, were framed to mimic an aesthetic familiar to the shelter magazine genre—very World of Interiors—the fireplace is lit, the objects are deliberately placed, yet no one is home. The film itself becomes an object of beauty, an objet, as you say, meaning it echoes the world it depicts, yet it also drops subtle clues along the way. This culminates in the auction of Provenance at Christie’s London, as seen in Lot 248, when the first in the edition of the film actually enters the market circuit it depicts. But there are earlier moments that fold back on themselves performing, as it were, the doubling of artwork and depicted object. The overhead shot of the cargo ship is itself an object that circulates through the world—it is a stock image, and has appeared in other works of mine, so this image of commercial transit, a cargo ship at sea, is itself an object that transits throughout several works, as well as in the world.

Scope: How does Provenance fit into your ciné-constellations?

Siegel: Initially the ciné-constellations were a group of cinema films—including The Sleepers (1999), Empathy (2003), and DDR/DDR (2008)—which mirror shared concerns in an essayistic, associative mode that is so loose, so personal, and connective that they were like constellations, wide montage both within and between works. However, since 2009, my work for exhibition—the multi-channel installations, photo-based works, etc.—began to take on those qualities, becoming layered, associative works made up of multiple elements that can function independently and together in an act of montage that is both interior to each element and between the elements themselves. Black Moon is a multi-element work comprised of a 20-minute HD video, a two-channel video installation, and 15 photographs. These are not “versions” of the work but independent elements whose meaning deepens when exhibited together. Provenance is also a multi-element work, but its elements unfolded in time, and from now going forward, that entire ensemble will be exhibited together.

Scope: The first time Provenance was exhibited was within the group exhibition, “Brute,” which you co-curated with Katarina Burin at Harvard’s Carpenter Center, Le Corbusier’s only building in North America. What was the impetus behind “Brute” and did working in a Le Corbusier building set off the far-reaching project that is Provenance?

Siegel: As artists attentive to architecture, as well as the overt presence of male architects (and absence of others), Katarina Burin and I conceived of “Brute” as a response to the Carpenter Center. The exhibition was not directly site-specific, but inserted newly developed works by artists we knew, including ourselves, who have an ongoing discourse with architecture, design, cinema, historical space, and the blurred boundaries between fiction and document, including Anna Barriball, Alexandra Leykauf, Barbara Bloom, and Nairy Bagrahmian, but with each artist those shared themes evidence in wildly different ways. For my own contribution I installed Provenance in the cinema of the Harvard Film Archive, in the basement of the Carpenter Center, and for the first time in 40 years, the black velvet curtain that has obscured the interior lobby window looking down into the cinema was pulled back to reveal the film, recycling daily. This particular installation of Provenance was a performance of the work, one which took on singular resonances as reflections of the Carpenter Center architecture in the lobby window would at time match up with the Le Corbusier architecture in Chandigarh, creating unique moments of double exposure, mirroring, a kind of speculative screen space.

Scope: What was your research methodology, and was it difficult to obtain permissions to shoot in private residences and in the auction house?

Siegel: My research methodology is my own obsessiveness. I find pleasure in pursuing this kind of detective work, in trying to locate each magazine publication and auction in which the furniture appeared, in tracing a connective path between things. I work intuitively, and my models are none other than the ciné-constellations themselves—a structural sense that things are connected if only I can locate the right path in between, whether from the friend of a friend of a friend who knows the designer who is credited with the house in a magazine spread where I located a Chandigarh settee after I entered keywords into the magazine website search engine, and then the designer contacts the homeowners, and a week later I am doing a location scout at their house…Certain residences were more challenging than others to secure permission, but I’ve been securing difficult locations for my work for long enough to know that a permission is a process, and even if it starts with no it can often end in yes.

Scope: Similarly, for a long time I did print source research for Cinematheque Ontario and relished the investigative nature of the job. There’s an innate suspense and pleasure in tracking a source and securing permission, and in getting lost along the way. I hadn’t thought of this initially, but there’s something of the journey in Provenance that evokes a time, becoming far less frequent, of routinely shipping film prints throughout the world.

Siegel: Right. There used to be whole films whose narrative structure was organized around print traffic, or the tours filmmakers make with their films—I’m thinking of Alice in the Cities (1974), or Les rendez-vous d’Anna (1978). Digital media is so immaterial, its transit is taken for granted, but this also opens up interesting possibilities of broadcast and simultaneity, which is something that preoccupies me. Issues of live-ness and cinematic séance surface in other ways, for example in my recent work Winter, which has a live soundtrack—voiceover, foley, music—that is different with each iteration of the work.

Scope: Were any startling discoveries made about Chandigarh, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, high-end furniture collectors, or the art market?

Siegel: More startling than the speculation the film itself depicts, and enacts? I didn’t spend much time researching Le Corbusier or Pierre Jeanneret after a point since the film unfolds in the present and maintains a rigorous adherence to its own condensed timeline. As an artist, one of the most startling discoveries I made was that the day after I finished filming in London, I went walking in the Hampstead Heath and visited Kenwood House, upon the recommendation of a friend, and there came upon a work by Hogarth, Taste in High Life from 1742, which was a forerunner to his satiric popular print series Marriage-à-la-mode. This painting depicted an aristocratic family surrounded by their accumulated things, and a monkey standing centre frame who examines a list of recent purchases at auction by the family. Seeing the Hogarth reminded me how un-isolated the acquisition of cultural objects, particularly the foreign, is. I was particularly impressed by the self-reflexive humour of Lord Iveagh, who acquired this work for Kenwood House, his home, to mirror his own family’s existence.

Scope: Taste in High Life seems so contemporary a title, yet that specific commission is also wryly upending a long-standing tradition of aristocratic self-portraiture with its satirical impetus. It’s astonishing that you fell upon this work at that very moment! The provenance of this Hogarth makes glaring the significance of context and how the latter shifts, slips, and elides over time.

Siegel: Yes indeed. Whereas in the Hogarth several objects are clearly from “the Orient” or Africa, one of the more fascinating aspects of the circuit of the Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret Chandigarh furniture is that these are Western architects whose work is being reclaimed by the west as such, but layered with the “exotic” patina of the east. A kind of reverse colonialism.

Scope: While Provenance enacts a rigorous timeline, it is obviously condensed. For how long did you shoot, and did you stay on course?

Siegel: Provenance was filmed over two years, and it was filmed almost in order, that is, in reverse. The final shoot was the India section. I actually made Winter—which is quite a large-scale project—while making Provenance, and I was flying from an artist residency in New Zealand to research Winter to location scouting in Chandigarh for Provenance. I came upon something interesting in Australia at the same time, not unrelated, which is the centre of a future project…

Scope: Did you discuss the diasporatic journeys of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s furniture with locals in Chandigarh? What is the present-day local opinion of Le Corbusier’s buildings and sculptures?

Siegel: The issue of the furniture I only discussed with a few select individuals in Chandigarh because it was a delicate issue—a scandal in Chandigarh itself for a time—so one had to be careful not to insult the very bureaucrat who may have been involved in the selling of the furniture.

Scope: Provenance shares affinities with Black Moon, your “condensed remake” of Louis Malle’s experimental science-fiction film of the same name from 1975, and, most recently, Winter commissioned by the Auckland Triennial, with its utopia/dystopia binaries and vertiginous landscape transition shots, its focus on ruins, however reconstituted, etc…How have your previous films informed this one?

Siegel: DDR/DDR, my feature film about the former East Germany, comes to mind. Its portrayal of economic changeover includes a mini-history of a design chair, as well as my parallel tracking shots…also Empathy, the Charles & Ray Eames lounge chair bit. Another work is The Modernists, composed of photographs and Super 8 film a husband took of his wife posed in front of modernist sculptures the world over from 1968-1986, that sense of modernism everywhere and “elsewhere” at once. I see the connections you are making with Black Moon and Winter, however I’m not so much interested in ruins as I am in the privileging in evidence of the new (ergonomic furniture, corporate interiors) over the old (modernist furniture now 50 years old). Western eyes view the Chandigarh buildings and perhaps think “ruins” but there are cultural differences here, and standards of environmental and building maintenance, that point to a much more complex story. These so-called “ruins” also have air conditioners now inserted in them, alternate entrances, windows, interior divisions that were not there before, they are still being altered, adapted, not merely left to entropy, though that is part of it. Le Corbusier actually built a “ruin” for Chandigarh, the Tower of Shadows, which tracks sunlight and reveals his “plan-libre” building structure, but is also very much, to me, a kind of 18th-century garden “folly” that has its roots in the French and English gardens of that era, forecasting the future ruin through ornamentation.

Scope: Why this privileging of the new over the old?

Siegel: Because that’s what I found there, in Chandigarh, a kind of interest in the new, and in physical comfort in a design form taken from the west, the task chair, cubicle, etc., better suited to the kind of work done now with computers, etc. It amazes me when people who see Provenance describe the long tracking shot in the renovated interior space of a Le Corbusier building as a call centre, bringing all their cultural assumptions with them. It is in fact a government office, part of the Secretariat, but the only renovated section of that huge building. These are civil servants, working on behalf of the city and citizens of Chandigarh. And they clearly privilege the new over the old, in fact keeping the furniture so new that they have left the plastic wrap on much of it.

Scope: I had forgotten about these previous “chair” episodes in some of your films. Now with Provenance, they retrospectively seem like preludes to the main event; having been woven into a larger story or history like those in DDR/DDR (which re-activates a specific historical discourse) and Empathy, here they are the story and history in one. Where does this fascination come from?

Siegel: That’s the ciné-constellation form I think you are describing, when something that feels partial in one work, or at one point in the work, is elaborated or turned into something new in another work, or a later moment. But the fascination, it’s hard to say exactly, except that I grew up in a fairly modern house in Chicago that my parents built with the architect Larry Booth, and its architecture and furniture made a big impression on me. And yet, I had fairly quiet, private parents, so I spent quite a bit of time trying to “read” the objects and space they designed as clues to the nature of these people I loved, who were quite mysterious about their own personal histories, for various reasons. A desire to understand how people exteriorize themselves through interior spaces, but amplifying that to an understanding of different cultures and the opacity of social class as well, perhaps. I think there are very disturbing things in Provenance, that underline cultural differences in the determination of value, and also in the fabrication of value, perhaps most acutely suggested in the furniture “restoration” scene in the workshop in Europe.

Scope: Speaking of The Modernists, you’ve made me think of the polemic surrounding the Centre Pompidou’s recent re-hanging of their collection “Plural Modernities from 1905 to 1970,” which attempts to chart the modernist movement across non-western regions. Aside from the architecture rooms, which primarily focus on India and Japan, the curatorial choices were severely criticized in some circles for misrepresentation. The show is fascinating and challenges preconceptions about modernism, its origins and its reach, and yet became fraught by insider debates. What is it about modernism and its icons that continue to command such fervour?

Siegel: I think it’s the radical response to the Victorian, the Beidermeyer, the wiping-the-slate-clean that modernism proposes, that still holds such sway with the imagination. Also the reach of the movement, the dispersal of so many of its practitioners before and after the war, pushed an influence far beyond Europe. I’m thinking not only of the artists who showed up in NY, but the architects that migrated to the west coast as well. The parallel ideas, such as psychoanalysis—a parallel discussed in Empathy—so intrinsic to how we live now, even if in their own dinosaur era. The pre-feminist aspect roils the blood, but also the bizarre adoption by post-colonial countries—in their first moments of independence—to look toward the European modernist architects to provide an aesthetic vision for a new future, of which Chandigarh was one city, Brasilia another. It’s fascinating to consider that compulsion.

Scope: At what point did you decide to put the film up for auction?

Siegel: The idea to auction Provenance—and film the auction of the film—was essential to the project and came to me quite early, within days of the initial idea for Provenance. The most difficult part was anticipating the unfolding of the action for the film. There was just no way to know what would happen, and where bidding would come from during such a packed and huge auction, with Christie’s specialists flanking the auctioneer on either side—there’s no advance shot list in that situation.

Scope: What had you predicted Provenance would sell for at auction? Did shooting the auction itself allow you to be detached from the situation?

Siegel: The Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary sale was over several hours, and each lot on average has about 30-60 seconds in an auction. Bidding on Provenance unfolded for four minutes, which is epic in auction time, but still extremely quick in a film shoot. I was so busy directing three cameras, that I barely had time to consider the astonishing nature of what was unfolding. I recall checking my phone shortly after and there was a cascade of ecstatic texts from people who had watched the bidding online, but it wasn’t until I was back at my studio and watched the footage that I understood the narrative of what unfolded and how the price escalated so rapidly and could also observe the pauses and lulls as well as the moments of intense action during Lot 248. While filming it just seemed so quick!

Scope: Bookended by Jasper Johns and Valie Export no less!

Siegel: Fascinatingly, it’s not actually a Johns but a work by Sturtevant—yet another layer of falsification that enters the story! Speaking of timelines, I found the sequencing of lots in that Christie’s sale a very interesting one…

Scope: Are any of your other films editioned? Has including other media in your moving-image installations altered your relationship to the art world? I’m thinking of the photographic prints that are an extension of Black Moon or the performative aspects and objects that are integral to Winter.

Siegel: All of my work is editioned, with the exception of the theatrical films Empathy and DDR/DDR. I’m interested in these multi-element projects having multiple lives and the varied existences: Black Moon was shown alone at Cannes, and together with the video installation Black Moon/Mirrored Malle and the Black Moon/Hole Punches series of photographs at the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, among many other exhibitions. There are certain works not meant to be screened theatrically, and others that have performative elements that can be realized in their entirety or on a temporal schedule. I’m interested in how their relationship to and divorce from their multiple components alters their meaning, and gives occasion for repeat audiences to view the works differently, as a larger act of montage.

Scope: Following the completion of Lot 248, Provenance is now also a multi-part installation comprised of two videos and one catalogue proof encased in Lucite. And yet, you also show the films in cinema settings, such as in the Berlinale’s Forum Expanded. Do you have a preference for how this work should be seen, and, aside the obvious black box/white box dichotomies, how much do you think the reception of the work fluctuates based on context?

Siegel: Provenance is a temporal project: its formal structure is a timeline of sorts that mimics the provenance document of an artwork. The introduction of Provenance into the world also formed a specific (condensed) timeline that mirrors the market trajectory of an artwork, from gallery to collector to auction. It is an accumulative, speculative work that took on further meaning as it moved through stages of exhibition and auction sale, and further elements were created each time, including Proof (Christie’s 19 October, 2013) and Lot 248. The full ensemble of works is complete and will be exhibited together going forward. As to exhibition context, my interest is not so much in theatrical film vs. museum exhibition as it is the further context of those exhibitions: How is the exhibition framed, what are the other works included? If in a festival, will it be in a section of artists’ films, will it have its own screening? Proper context for the work as an artwork is the most important thing. I do wish more film festivals—who tend to program en masse these bulky omnibuses of intense duration—would demonstrate more sensitivity to that. I am already working with multiple elements that create a montage between the works, I don’t permit these works to be part of a screening program with other works. However, I’m often pleased to have them included in a festival section that is clearly searching out rigorous and new work by moving image artists.

Scope: The following statement appeared in the Christie’s auction catalogue and is exhibited in the context of the installation as a printed proof in a Lucite box: “Executed in 2013, Provenance marks a pivotal moment in the artist’s career, turning as she did from pictorial devices of simultaneity to address the spectral possibilities of temporality by using a slowing revealing timeline.” Who wrote this?

Siegel: Christie’s catalogue articles are authored by their specialists and editorial department for their auction catalogues, including the prose descriptions of the artworks coming to auction for that sale. I had little to do with this. They tend to adopt a particular tone, and they research the career and work of the artist discussed, as well as the particulars of the artwork, or lot, for sale. But I found it rather perfect.

Scope: What will you do with the funds obtained from the auction?

Siegel: My desire is to exhibit Provenance in Chandigarh, in a cinema designed by the Le Corbusier team, to screen the works for a week, for free, for anyone who obtains a ticket. However, I recently heard the cinema is scheduled for renovation, so I better hurry before those cinema seats disappear and end up at auction houses around the world…

Andrea Picard