A Film/Art Hypothesis: Philippe Parreno at HangarBicocca

By Andréa Picard

L’année dernière à Marienbad (1961) is an enduring, mesmerizing modernist masterpiece. Perhaps the most powerful aspect of this Resnais/Robbe-Grillet collaboration—apart from its dapper design (including trimmed topiary) and Delphine Seyrig’s divinely breathy intonations and Chanel plumage—is its constant creation of spatial and temporal ambiguity, its perverse usurping of causal relationships between events and people, equivocating as uncertainty in the mind of the viewer. The film’s deeply enigmatic and somewhat musical narrative structure invokes partition-like perception play and swiftly exposes the wall separating fiction and reality as porous and easily retractable. That the film still divides today, its status as masterwork intact and unequivocal on the one side and its charges of academicism, pretension, and downright boringness on the other, suggests the obvious: intellectualism in art remains an easy target, especially when narrative-resistant and open-ended in what appears, paradoxically, to be a closed, cloistered, and safe system.

It is therefore not so outlandish that Marienbad came quickly to mind when I stepped into the dark, cavernous Navate exhibition hall of Milan’s impressively large HangarBicocca contemporary art space to view Philippe Parreno’s recent solo show Hypothesis, curated by Andrea Lissoni. Often considered heady and highly conceptual, masterfully controlled yet mysterious, the work of the prominent French artist has been, perhaps inevitably, more susceptible to critique for its illustrious institutional affiliations and grand (and expensive) gestures since his massive retrospective shows at the Palais de Tokyo in autumn of 2013 and at the Park Avenue Armory in New York last summer. The question seemed to be: How to be monumental and meaningful without being lumbering, self-important, and overtly imposing during his ongoing investigation into the potentiality of exhibition-making as expression? I missed the Armory show (unpredictably disparaged in The New York Times by art critic Roberta Smith) and felt the artist’s keen takeover of the Palais de Tokyo—the first time a single artist was given reign of the entire 22,000-square-metre gallery—was often enthralling and ingenious, but perhaps predictably an impossible task in such a sprawling, detached, and cold space; the distances between the “relational aesthetics” for which Parreno is known were both far too vast and diffused and too contained and compartmentalized. The segmenting onto 17 screens of one of Parreno’s most iconic works, his feature-length 2006 film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (co-created with Douglas Gordon), simply did not function as a diffracted portrait meant to stymie a fateful moment. The show ultimately proved to be exhausting in footprint and sensory intake/deflection, despite intermittent flashes of brilliance and real ingenuity throughout.

Hypothesis, however, while being a relatively smaller-scale iteration of these two previous monolithic shows, displayed a mesmeric mise en scène and a rigorously orchestrated, perambulatory timeline. A feat of choreography that invoked a linear yet infinitely looping pattern of lights and sound along algorithmic shifts, the show began with an exquisite prelude: American artist Jasper Johns’ set pieces for Walkaround Time, the Duchamp-inspired 1968 dance performance choreographed by the legendary Merce Cunningham. Taking the constituent parts from Duchamp’s infamous The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) and translating them into seven PVC inflatable “pillows,” each painted with the images from Duchamp’s large glass, the set pieces were hung high from a white square-shaped drop ceiling at the Hangar and dramatically overlit. It was a bold and unexpected initial encounter, a piece markedly not by Parreno, but one that relates to his recent role as exhibition designer (specifically, as metteur en scène) for a major 2013 show at the Barbican titled The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns.

Metaphorically, Johns’ sculptures set the stage for an entrancing walkabout through time and space, a dreamlike experience of an exhibition that is perhaps best described as dazzlingly cinematic. With a huge, floor-length black curtain draped from the Navate’s massive ceiling behind the illuminated plastic specimens, a clear design plan was articulated, one continuously enlivened the more one penetrated the longitudinal, industrial space. A former factory plant for the manufacturing of railway carriages and farm machinery, the Hangar has retained its industrial architecture since Pirelli converted the expansive warehouses in 2004 into a destination for adventurous programming in contemporary art. When the building was unveiled, so too was a massive, permanent Anselm Kiefer sculpture titled The Seven Heavenly Palaces, consisting of seven hunkering, stand-alone concrete tower blocks erected in the centre of the main exhibition hall. A major commission and likely also a destination draw, the Kiefer obviously poses intriguing curatorial challenges. Excised from Hypothesis’ exhibition space altogether, the towers were not on display here; instead, the space was fully bifurcated, and a long (shock) corridor-like swath was used along the right wing of the hall. Still extraordinarily massive, but providing a cogent layout which revealed itself in a series of technological animations, the space itself became a major component of and catalyzer for the show.

With exposed girders, cross supports, steel columns, and vault-like elevation, the space provided amble opportunity for formal shadow play, abstract symmetries, and dystopian fantasy, as Parreno cleverly incorporated the striking industrial hallmarks of the building into a dramatic schema in which, not unlike that in Marienbad, spatial dimensions and temporal signs transcended all certainty and were transferred oneirically. Like an omniscient convener, Parreno summoned ghosts from the machines—the aura from the site, but especially from some of his singular and iconic works, which were recombined in a radical way so as to emphasize a collective, time-based experience similar to cinema-going. Symbols of seriality abounded, from the structural geometric grids, to Danny the Street (2006-2015), 19 pieces from Parreno’s Marquee series named for the fictional DC Comics character created by Grant Morrison and Brendan McCarthy. Danny is an actual street in the DC universe (a sentient one, which can transport itself to other cities), but Parreno’s Danny is comprised of big, bright Plexiglass sculptures of multiple dimensions and sizes which emit both light and sound, and recall the opulent and festive cinema advertising marquees of a bygone era, specifically those of classical Hollywood. In Hypothesis, they hung and hovered from various heights over two floor-bound and intermittently spotlit Disklavier pianos, which bracketed the “street” and spectrally performed the score that determined the timing sequence for the entire exhibition.

The musical score was conceived by Parreno and Nicolas Becker and consisted of numerous other collaborations, including a composition by experimental musician Robert AA Lowe (from Lichens and A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness [2013] fame). The piano pieces were part of a more complex orchestration that integrated the light and sounds from the Marquees, ones which were uncannily and precisely in synch with the beginning and ending of all of the show’s elemental parts, including the films and videos. Far from an unwieldy Gesamtkunstwerk, Hypothesis moved away from the fetishization of the object and instead argued for the show’s overall effect as a live, situational, and deeply sensorial experience masterminded by an invisible puppetmaster (yes, Parreno, but via a master computer hub, a sort of invisible Kubrickian master control). The strength of the individual works—a greatest-hits compilation—was harnessed to create an atmospheric, immersive plunge into a dramaturgical, nearly two-hour event with proto-cinematic effects.

As one followed the flow—cohesive, captivating, and also jarringly disjunctive—of the sound and images activated throughout the space, an unsettling sense of inevitability arose. As visitors walked, paused, listened, sat, watched and, yes, posed for selfies amid an array of impressive, backlit chiaroscuro self-reflections, the movement of life and its refusal to stand still became eminently palpable, not simply a metaphor at a remove. Within the cavernous and cacophonous space in which our movements were both free yet directed, the internal and external rhythms of the show inevitably propelled us forward. Hypothesis had an automaton-like quality but was so filled with sensual delights that one came to understand how a street could be sentient, and disorientation could be as exhilarating, unsettling, and arresting as in early city symphony films; the visual echoes of silent and early sound cinema ranged from Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) to the kino-eye films of Vertov and Rodchenko, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and M (1931), and the incredible silhouette animations of Lotte Reiniger.

Suspended opposite the Marquees was Another Day with Another Sun (2014), Parreno’s collaboration with artist Liam Gillick, an artificial spotlight that travelled through the entirety of the exhibition space on a tracking system and suggested the passage from daybreak to nightfall. As it traversed from one end to the other, it illuminated the structural elements in the space as well as the Marquees, casting harsh, oblique, and playful shadows upon the floor and moving along a massive drop curtain created out of a specially treated white textile which formed the main longitudinal wall encasing the exhibition space (and conversely enclosing the Kiefer on the other side)—an entrancing and expressionist phantasmagorical landscape come to the life, as if it had emerged from a turn-of-the-century magic lantern.

The old converged with the new on the final Marquee in the row. A sort of souped-up, futuristic digitized sandwich board, this Marquee was a large stand-up screen comprised of a pattern of LED lights on which a rotation of three Parreno films was shown: Anywhere Out of the World (2000), part of the artist’s project with Pierre Huyghe, in which the duo purchased the rights to a Japanese manga character whom they named “Annlee,” releasing her from copyright and into the hands of other artists; Alien Seasons (2002), a silent, strangely seductive film about a species of giant cuttlefish which possesses photochromic mimetic capabilities allowing it to modify its iridescent skin colour; and With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (2014), an animation made up of hundreds of drawings of fireflies, which, like the screen upon which their representation comes to life, emit intermittent luminous signals in order to communicate. The images in With a Rhythmic… appear and disappear on the LED screen according to the algorithm of the “Game of Life,” a cellular automaton devised by British mathematician John Conway in the late ’60s; the algorithm also converts the intensity of light into sound. While conceptually rather dense, the effect was one of pure enchantment.

A simple black bench was placed in front of the Marquee screen, and from there one could see the cast shadows of those basking in the low-lying light of Mount Analogue (2001), a floor-bound, lens-less projector beaming monochromatic light sequences in a diagonal spray. Green and purple were the two dominant colours when I was there, adding a welcome wash of colour in a largely black-and-white show; Annlee’s glowing turquoise shirt and the deep crimson in Parreno’s latest film, The Crowd (2015), provided the other bursts. Inspired by the eponymous, unfinished cult novel by René Daumal (a major influence on Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain [1973]), the light progression in Mount Analogue is based on a translation of the novel into Morse code. Impossible to know this from experiencing the work, its conceptual and cryptic nature was also translated into more concrete and simple pleasures with recognizable indexes—a hallmark of Parreno’s probing work in general. Bookended by Johns’ Walkaround Time set designs and Mount Analogue, with its obvious affiliations to the tradition of expanded cinema, Hypothesis testified to the artist’s deeply inquisitive nature, his phrenic focus, his sensitivities to aesthetic beauty, and his montage-like process.

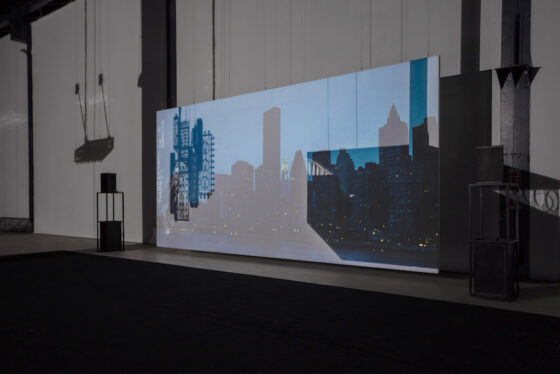

And what of the films, then? A consummate cinephile—not unlike his fellow French artists Huyghe and Dominique Gonzales-Foerster, with whom he has had a long, engaged, and collaborative affiliation—Parreno has frequently integrated cinema into his work, his enthusiasm formed and buoyed by the likes of writer and theorist Serge Daney and scenographer Jacques Polieri. Four of his films—The Boy From Mars (2003), Invisibleboy (2012-15), Marilyn (2012), and The Crowd—were shown in the centre of the exhibition, projected onto a large screen which doubled as an abstract canvas during the “entr’actes” when the house lights were abruptly brought up, exposing the entire show’s armature and effectively rendering the visitors vulnerably bare. With the lights on, the supports of the screen emerged like an incandescent white painting (Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting (seven panel)?), and when the films were projected (the projector ingeniously tucked into one of the hanging Marquees) their images and sounds became interwoven into Hypothesis’ hyper-orchestrated visual and aural procession.

Eschewing the black-box model and shown in an open designated area (with a black carpet to prevent light bouncing from the floor), the films evinced a polished, self-reflexive style that was perfectly aligned with the show’s moody world, tinged with noir, Gothic, and dystopian overtones. Marilyn, a ghost portrait of Marilyn Monroe in the Mad Men décor of the Waldorf Astoria where the actress once resided, is awash in atmosphere and absence. Never represented onscreen, Marilyn is paradoxically evoked through breathy voiceover confessions and close-ups of her handwriting, both of which are reproduced through a mathematical algorithm. The meticulous reconstruction of her suite and its eventual meta-reveal as the camera tracks back beyond the confines of re-enacted fiction mirrored the in situ environs as if the entire exhibition were, in effect, one large film set. The Crowd, which was shot in and first shown at the Park Armory during Parreno’s elaborately titled H{N)Y P N(Y}OSIS show, continued this vibe as one watched viewers watch a sizeable, somnambulistic crowd bathed in scarlet wandering in the direction of a player piano, being beckoned amidst an experience not unlike that at the HangarBicocca, and thus forming a beguiling mise en abyme. When sitting on a bench behind others, whose obstructing heads compromised the optimal C-value of one’s sightline, their silhouettes contributed to the layers accruing and conflating spectatorship and spectacle so intrinsic to Parreno’s films.

With its own temporal discontinuities and staccato movement through space, Hypothesis created a hermetically sealed world of bewitchment in which chance and precision conspired in presenting a reality that was, at once, illusory and viscerally felt. As with Marienbad’s conflicted and ambivalent relationship to art, demanding that we view its formalist construction as real, not an elusive copy, Parreno posits the simulacrum in what we see. All the while engaging with machines and the immaterial, the artist has convened the unexpected into intimate and collective encounters that are precisely tuned yet drawn to theatrics. Ultimately, his work is about collaborative thinking, perpetual (and perceptual) renewal, and the power of the imagination (and the cinematic imaginary), positing an opening that leads the spectator into nested worlds where perspective is parsed for its authoritative allure and, thankfully, its equally wayward possibilities. As the show at the HangarBicocca made eminently clear, this is a hypothesis well worth making.

Andrea Picard