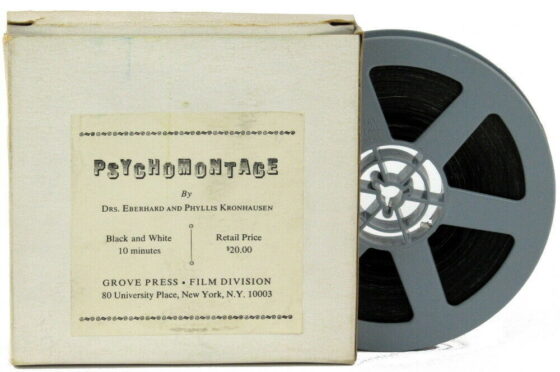

Exploded View | Eberhard and Phyllis Kronhausen’s Psychomontage No. 1

By Chuck Stephens

A snippet of nature footage depicts crickets pitching chittering woo; smash cut to a newsreel shot of a wrecking ball demolishing a tower. A hapless Foley artist ooks and grunts an approximation of a spasmodic chimp; a blonde in black stockings canoodles with her canine in a glade in a public park. The male gaze intrudes…wait, is that Taylor Meade? (No.) A shabby cymbal-and-bass stroll slinks across the soundtrack, less stripteasical than pallid pink panther. People get naked, lips are smacked, groping ensues; macroscopic pondlife lick and suck, bomber pilots release their loads. In ten neurotic minutes, the movie climaxes again and again. Come-on, or plain comedy? Evocative of Ovid, or an altogether obvious joke? Take it off! Take it all off! Take my associative montage…please!

In order to make any real sense of pop-culture sexologists, erotic art connoisseurs, and horny highbrows Eberhard and Phyllis Kronhausen’s 1963 curio Psychomontage No. 1, one probably needs to give late-’50s/early-’60s culture a slight whack upside its head—just enough to displace the cosmic lineup such that Bruce Conner is re-rendered as the naughty nightclub-chanteuse, party-record poetess, and sexual revolutionary Rusty Warren (RIP), and Conner’s 1958 found-footage masterpiece A Movie is summarily chopped and screwed into Warren’s classic 1960 dirty-talk album, Knockers Up!

A mild turn-on for 1963 audiences, Psychomontage was meant as a Rorschach blot for the loosened libidos of swinging couples, but it seems at the time to have been just a minor diversion for the German-born Eberhard and the American Phyllis: they’d met at the University of Minnesota in 1954, married, and pursued parallel degrees and careers in education and psychology. They specialized in sex: as academics, studying human sexual behaviour in the Kinsey era, and as collectors of erotica, which they exhibited internationally and compiled into the two-volume Erotic Art (Grove Press). They were ubiquitous during the ’60s sexual revolution. Frank Zappa even thanked Eberhard in the liner notes to Freak Out!

Not exactly “experimental”—more an arty, adults-only gag reel, and once upon a time sold by mail, like an 8mm stag film, by Grove Press’ film division—Psychomontage No. 1 is a sort of silly one-off, even as it interfaces with the couple’s wide-ranging fascination with erotic pop art and prefaces the next phase of the Kronhausen’s extraordinary set of careers: as pioneering sex-filmmakers during the Danish proto-porn explosion of the early ’70s. What had been an apparently passing interest in purely formal cinema on Psychomontage No. 1 morphed, quite lucratively, into the kinds of erotic Mondo movies Travis Bickle might have found appropriate to take a date to: half heartfelt documentaries and pleas for sexual diversity, half delirious pandering, with titles like Freedom to Love (1968), Why Do They Do It? (1971), and Sex-cirkusse a.k.a. The Hottest Show in Town (1974). Though there was no Psychomontage No. 2, every film the Kronhausens touched after making that first one was a kind of sequel to its underground success.

Amos Vogel, who screened and made the film available through Cinema 16, was typically lucid (in Film as a Subversive Art) in describing Psychomontage No. 1 as an “attempt to induce erotic response in the audience by carefully chosen visual stimuli and juxtapositions (aimed at both conscious and unconscious). Phallic symbols and open orifices, a tongue licking an orange, an unexpected finger entering the frame: almost any object or act, no matter how innocuous, the Kronhausens show, can be made to appear erotic, and reveals our predisposition towards ‘shaping’ visual evidence for purposes of erotic gratification.” An IMDb commenter with some apparently deep-crate knowledge about ’60s smut suggests that the bits with the dog-walking blonde and her peeper come from a stag reel called La petite mort. What role William Burroughs collaborator Antony Balch may have played in Psychomontage No. 1’s “special photography,” one can today only guess. A furry chestnut from the past, Psychomontage No. 1 remains enigmatically blot-like: a celluloid stain that somehow refuses to fade.

Chuck Stephens