Vancouver: Dragons & Tigers & Children

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

Conventional wisdom says that a film festival jury should always have a talent spread; that is, a director here, an actor there, perhaps a critic or an academic or a programmer tossed in for good measure. This is because, as a rule, in every unscientific study ever done on the matter, directors and actors tend to select more conservatively, close to the mainstream, while non-filmmaking folk tend to lean more radically.

The mix supposedly balances things out, with “sensible” results ensured. (This perception is, of course, ruined at every turn, such as at this year’s Cannes, where a director, Tim Burton—helped by another director, Víctor Eríce—pushed his jury toward the most radical film in the official competition, Apichatpong’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.)

An all-director jury is certainly not conventional. But the assembly in Vancouver for the Dragons & Tigers Award for Young Cinema of Denis Côté, Jia Zhangke, and Bong Joon-ho announced something different. Not only that each are serious cineastes of the first order, nor that each is a lifelong student of cinema, not even that their films collectively evince a cinephilia that goes beyond the level of artistry toward a sensibility informed by the lessons of film and film history. More crucially, each has proposed through their work alternatives to dominant cinema, whether Côté through his deeply ingrained fascination with the body and nature as a map on which we can read a “narrative”; or Jia through his re-enchantment of silent cinema and Bazinian ideals of space and time by way of an ongoing ambition to chronicle Chinese history; or Bong through his muscular revisions of genre, neither thoroughly transgressive nor blatantly affectionate, but critical and intent on exploring every sensory aspect of cinema.

What in the eight-film D & T competition get them out of their seats? It’s worth noting for the record the field they were choosing from, characteristically representing the competition’s geographic spread and weighting toward first films: Phan Dang Di’s Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! (Vietnam); Jo Sunghee’s End of Animal (South Korea); Hirohara Satoru’s Good Morning to the World! (Japan); Abe Saori’s and Takahashi Nazuki’s Icarus Under the Sun (Japan); Thanwarin Sukaphisit’s Insects in the Backyard (Thailand); Park Donghyun’s Kimu; The Strange Dance (South Korea); Xu Ruotao’s Rumination (China); Boo Junfeng’s Sandcastle (Singapore). Phan’s and Boo’s films came to Vancouver from Cannes; most came directly from Asia, reinforcing Vancouver’s crucial position as the prime North American gateway for progressive, radical, and independent films by young Asian filmmakers.

The choices reflected was a kind of deep-tissue involvement with the films, and a keen perception of the films that both accomplished something major and branched out in new directions. The winner was 23-year-old Hirohara’s Good Morning, an impeccably filmed kind-of coming-of-age tale about a high-school boy who may or may not have witnessed the aftermath of a killing, and his cockeyed attempts to intuit injustice and balance the scales. The runners-up (or winners of “special recognition”) were just as good, if not arguably better films: Xu’s extraordinary Rumination, a fractured mosaic about a squad of Maoist Red Army guards running amok in the countryside, and Phan’s Don’t Be Afraid, on the surface a typical piece of art film poetics that is actually a darker and more elusive animal dealing with the uncertainty of perceptions and the strangeness of the world through a child’s eyes.

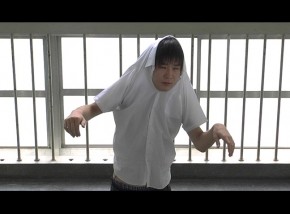

With Hirohara, you have a clear case of a major filmmaker in germination. From the first scenes, he applies two strategies that serve him well throughout the film: a determined focus that eliminates all details but those most essential, and a disciplined regard for whatever he’s filming that’s neither overtly sympathetic nor frigidly distant. In these matters, Hirohara appears to be a close watcher of Kore-eda, a master of such discipline and balances. He also shows a fascination with the element of surprise, or at least the unexpected: his film doesn’t open on his main character, Yuta (Koizumi Yoichiro), but on a loose gang of twenty-something guys who regularly get drunk, blow up stuff, and seem to make a lot of noise without much harm. A good subject, but this isn’t Hirohara’s interest. Yuta lives in his bedroom, or goes straight back and forth from school; notably missing is his mother, whose absence is eerily not commented upon, and even less explained. That Yuta manages well on his own isn’t something Hirohata is willing to turn into something heroic—it simply is. Yuta may be seen as a cousin to the kids left home alone in Kore-eda’s Nobody Knows (2004), but the dramatization here is more radical and even less psychological, and in any case upsets any parents’ fears of the prospect of a kid fending for himself. Yuta seems to be fine in school, and entertains himself on his bed, fantasizing himself to be a rock star.

Hirohara glances at the high-school genre (a real genre in Japanese cinema, whose most sensationalist example this year in Nakashima Tetsuya’s Confessions), but again, he’s not really interested in it. The homeless man in a tunnel who Yuta passes every day on his school route is suddenly found dead (very possibly killed by the gang one night), and Yuta engages in sleuthing to find out his identity and past life. Good Morning to the World! becomes a parable on uncertainty: the man’s name may not be what Yuta first thought it was, and he in the end it’s possibly he isn’t dead. No amount of “clues,” pieces of paper, or photos deliver any hard answers, and the people he meets on the way (including a truck driver who was once a guitarist in a band named “Frank Panda” and can easily be seen as Yuta in future form) appear lost or at least displaced from where they should be. And when Yuta’s mother reappears at home as if nothing has happened, the lack of certainty is all-encompassing. The only certainty is that Hirohara always knows the right place to put his camera, and the right tone somewhere between comedy and absurdity, drained of melodrama.

Phan Dang Di’s film is finally not too far from the sensibility in Hirohara’s. Set in contemporary Hanoi, but in a home and neighbourhood that reeks of the French colonial period, it dwells on a six-year-old boy named Bi (Phan Thanh Minh) whose endless curiosity is the film’s signal of a character fully engaged with life. This is in contrast to his parents, whose alienation is total: his dad is almost never around, spending every possible moment at gaming tables or with a masseuse cum hooker and would-be lover, but whom Phan doesn’t cast in judgment. Bi’s mom must care for his grandfather, who is being brought to the house for rest and, very likely, his final days.

Phan’s mentor is clearly Tsai Ming-liang, or at least he shares Tsai’s obsession with water, which is everywhere in Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! He views it sensually, as much as possible through Bi’s point of view, and the forms of water—in frozen and liquid state—progressively carry darker meaning. A nearby ice plant is Bi’s favourite playground, but the ice blocks attain more sinister dimensions by the end, visually associated with the grandfather’s death and his father’s thoughtlessness, so shocking that even Bi’s kindly aunt can take no more of it. More than in Adrift (2009), which Phan wrote, the interaction between visual symbols and the characters’ experiences are beautifully integrated. It may have had to do with viewing both Good Morning to the World! and Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! in one setting, but it was hard not to notice that each film ends with the young protagonist interacting with flying machines (a hot-air balloon in Good Morning, a commercial jet in Don’t Be Afraid). Neither is used in the trite sense to suggest freedom, but rather a rupture in what has led up to it, possibly a departure toward parts unknown.

Xu Ruotao’s Rumination, on the other hand, is fabulously sui generis, even amongst more adventurous Chinese independent films, but like Hirohara’s and Phan’s films, trains its attention on children. These however are grown children—stunted may be the best term—members of a Red Guard unit whose mission appears to be permanent revolution, which is to say, chaos. This is certainly the harshest film attack on the madness of the Cultural Revolution, since it deposits the viewer into the period without comment or context, and plays tricks with time and history. Xu presents the Guards as a collective human monster from whom no one can escape, while also being a wretchedly inept bunch of ragamuffin idiots whose “knowledge” is nothing more than spouting Maoist cant. Xu tackles cinema not so much as the visual artist he’s been up to now—he’s known as an abstract painter—but as an artist intent on creating a revolution within cinema. That’s not to say that Rumination isn’t continually complex and rich in its visual approach. Xu steadily shifts from semi-realist settings in barns and farm houses in the countryside, where the guard members regularly hunt down and beat the shit out of anyone they wish to—sort of like Alex’s A Clockwork Orange droogs only with a government license—to more and more theatrical interiors, where action gives way to displays of Maoist icons and symbols, the same empty language spouted but now without any meaning, because meaning has been drained out of this “revolution” by degenerate violence. Xu’s editing and camera movements are controlled and yet amped up, with a feverish sense of a world cracking up expressed in a weird, creepy chain of sequences whose relentless ferocity is probably the closest thing to the Cultural Revolution’s crazed militarism without having been there. These are the children of Mao, but there’s not a Coca-Cola in sight.

Robert Koehler