TIFF Preview -5: The Master | Denis Côté on Bestiaire | Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang | Gangs of Wasseypur | Just the Wind | Perret in France and Algeria | Pusher | The Reluctant Fundamentalist | Rust and Bone

Cinema Scope 52 Preview

The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, USA)—Special Presentation

By Gabe Klinger

The evolution in Paul Thomas Anderson’s oeuvre towards impeccably researched, stunningly visualized mythological explorations of the American character in There Will Be Blood (2007) and The Master represents a sterling 180-degree turn. Staying within a certain autobiographical comfort zone in his first four features—Hard Eight (1996), Boogie Nights (1997), Magnolia (1999) and Punch-Drunk Love (2002), which, seen together, comprise something of a subjective history of contemporary Los Angeles—the recent films ambitiously work to place Anderson’s omnipowerful magnates against a sprawling historical tableau, expanding his temporal and geographical reach by decades and to far-flung corners of North America and beyond. Simply put, Anderson has become a more inherently interesting writer, researcher, social critic, and painter.

Discarding ensemble pieces in favour of intimate character studies, he has opened his films up to more focused performances, with Daniel Day-Lewis’s Daniel Plainview being arguably his greatest creation. There Will Be Blood announced the end of a protracted calling-card phase in Anderson’s career, and The Master, an equally impressive achievement, confirms that his intent is a serious one. Like Stroheim with Greed (1924) or Vidor with The Crowd (1928), his cinema has entered its visionary stage—and boy, let’s hope it stays in it. Anderson may still get called out for his narrative imperfections (see Adam Nayman’s summary of PTA’s faults and virtues in Cinema Scope 50), but there isn’t a cinephile on the planet—at least none in my own midst—who isn’t salivating to see what he does next.

Bringing to mind Sam Fuller’s The Steel Helmet (1951), one of the earliest shots in The Master is a dramatic close-up of a battle helmet donned by Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), presumably at the end of his term as a Navy man in the Pacific theatre. Much later, Quell will announce that he obtained 13 battle stars and how he was on the “boat that saved the war.” Anderson sets the tone with General MacArthur’s speech aboard the USS Missouri as we see Quell crawling around in the lower depths of a torpedo vessel and hanging aloft in the masts of a battleship, his fellow seamen hurling objects at him (like many shots in The Master, this moment doesn’t seem to be compatible with any plausible reality). Proceeding into peacetime, Quell and several other recruits are hanging out on a beach where they sculpt a large-breasted figure in the sand. In the first indication of his full-scale lunacy, Quell begins to make love to the inert siren.

And the postwar drift begins. Back on the continent, Quell lands work snapping portraits at a department store (perhaps the most lovingly recreated period details in the film are the Technicolor-tinged master shots of Freddie’s subjects). After an unprovoked row with a customer, Quell moves on to cabbage fields tended to by what appear to be formerly interned Japanese. Disenfranchising himself from every itinerant task presented to him, he winds up sneaking onto a luxury ship in the San Francisco bay chartered by one Lancaster Dodd (Phillip Seymour Hoffman), or “Master,” a self-professed philosopher, physicist, author, and sea captain, but most of all a spiritual leader of dubious origin. Having recently parted ways with one cause, Quell’s troubled loner latches onto Master’s “The Cause,” which is based on the belief that men are plagued by the failures of their former lives, and that they must tame their animal instincts in order to reach the innate perfection of their psyches…or something. If you haven’t already connected the dots to this belief system’s lunatic real-world, multi-million dollar institution, you probably live under a rock.

Beyond passing out flyers, subjecting himself to sadistic examination, or taking book-jacket photos for Dodd, Quell evolves an ambiguous henchman relationship with Master in the way he goes so far as to brutally assault those who dare question the Cause’s methods. Though the off- and on-screen violence in The Master certainly lingers in the mind—one questions whether these confrontations initiate solely from Quell—it’s the powerful suggestion of Dodd’s influence on his environment in certain enigmatic scenes that reverberate chillingly. An orgy hosted by Master that would resemble Eyes Wide Shut (1999) if Kubrick had transplanted the setting of his film from the wealthy ‘burbs of New York City to the boonies of Wisconsin, is something like the salacious height of The Master’s abstruse portrayal of the Cause.

The Master settles on a strategy of presenting scenes concerning the relationship of Dodd and Quell parallel to oblique depictions of the Cause’s activities. Quell rarely seems up to the tasks presented to him, unless they involve physical contact, or him concocting paint thinner hooch to consume together with Master. Even when Master engages in extended interrogations of Quell—these lengthy sequences present Phoenix with the opportunity to exhibit his most impressive range of facial contortions—the revealing of a wounded past relationship with a girl named Doris is emotionally devastating but never sets up the character for a total immersion. “Perhaps he’s past help,” concludes Dodd’s wife Mary Sue (Amy Adams), a discreet influence on Master who is seen, in one of the film’s truly oddball moments, ferociously masturbating her husband in the bathroom.

Much of The Master builds up to explosions, and while there’s no denying that the different displays of Master’s outlandish theatre of pseudoscience evidence a superior design and execution, Anderson’s continued reliance on “show-stoppers” (per Nayman) to advance the drama remains mildly troubling. To his credit, Anderson has at least come to the conclusion this time around that he doesn’t need to go out with fire and brimstone—no milkshakes drunk, no frogs. Significantly, too, The Master does not look as elegant as There Will Be Blood. Its visual palette is more varied and less predictable. In addition, much of the film’s sombre action is moderated with humour (Quell is ultimately tragicomic), and significant departures are made from the storyline that seem owed entirely to last-minute editing decisions (Anderson has confirmed this, at least of the film’s final shot). The Master’s skewed chronology and elliptical editing are perhaps two aspects of the film that will reward on a second viewing.

Lastly, it might be worthwhile to explore some of The Master’s thematic divergences from There Willl Be Blood. If the earlier film suggests the corrosive power of industry (oil), let me propose an opposite formulation for The Master: the corrosive industry of power (religion). Much will be made of Phoenix’s Quell, whose psychotic outbursts are spectacularly envisaged, but it’s Dodd who is the genuinely seductive creation, and Hoffman’s uncanny embodiment of the title epithet is the subtler, more rewarding performance. (Perhaps Hoffman’s recent stage turn as Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman helped the actor form the basis for Master’s period affectations.) Quell progresses through the narrative largely unchanged, while it’s evident that Dodd grows more powerful and resolute. A frustration of The Master is that Anderson never fully decides which character he is more invested in—superficially, he might have gained more from Dodd. Quell starts and ends on the beach, a spectral, unresolved presence. By bookending the film with these images, Paul Thomas Anderson suggests that Freddie Quell may have never existed.

The Animal Equation: Denis Côté on Bestiaire (Denis Côté, Canada)—Wavelengths

By Denis Côté

“God invented the cat to give man the pleasure of petting a tiger.”—Victor Hugo

The world of images confirms that we love animals in order to convince ourselves of our superiority over them. To reassure himself of his own humanity and to demonstrate his interest in beasts, both real and legendary, the man from ancient times would scribble down summary stories: bestiaries. Today’s man gorges himself on YouTube. No need to dwell on the entertaining virtues—often real—of wet kittens in the sink. But can we not lament the harm done by this display of curiosities taken on the fly to the precision of gaze that others so desperately chase? At the other end of the spectrum lies the illustriousness of National Geographic, Animal Planet, and other toadying televised inventions.

But where is the salvation between the puppies on YouTube and a boa constrictor’s reproductive cycle narrated in eight chapters? How should one look at an animal (and find a cinematic language specific to this act)? Is it possible to shoot animals other than through the lens of entertainment or for a non-educational purpose? Neither actor nor story catalyzer, cannot an animal be contemplated and filmed simply for what it is?

The cinema loves to ennoble animals, to plaster them with emphasis and artificial scenarios. And naturally, the audience is smitten with this aestheticization, as proven by the phenomenal success of Winged Migration (2001), March of the Penguins (2005), and Oceans (2009). Because we find it beautiful, it’s that simple! It’s a matter of communing with the species: the penguin waddling on an ice floe or struck silent during a storm will always have a radiant place in the world of public distraction.

What the cinema adores above all is anthropomorphism. From Benji to Disney by way of Tim Burton’s creatures, Babe, the pig, E.T. (let’s cheat a bit) or King Kong, the animal is us, our trials, our anguish, and our relation to the world. Reflections of our valiant as well as failed attempts, Lewis Carroll’s rabbit and La Fontaine’s fallacious fox can’t stop reminding us of our own shortcomings, which we are all too eager to forget.

Barbet Schroeder’s very beautiful Koko, A Talking Gorilla (1978) is a hymn to tolerance and communication. We catch the researcher Penny Patterson more than once referring to Koko as one of her offspring! In Nenette (2010) by Nicolas Philibert, the orangutan serves to reveal the comments and reflections of those who paid a sum to temporarily flee the boredom of their human condition. Weird as always and slightly out of step with the world, Werner Herzog, in the incredible Grizzly Man (2005), uses the footage of an improbable character (a kind warrior!) who gave his life in order to convince us that he was a bear. In Ulrich Seidl’s misanthropic and very head-on Animal Love (1996), the filmed doggies become the receptacles for human distress. If the semi-doc achieves in imbuing us with a sympathy for animals, its strange zoomorphism serves to succeeds the appearance of a sad race of sub-human suburbanites. What cinephile has forgotten The Story of the Weeping Camel (2003), with these humped, hairy near-humans and veritable semi-gods of the screen? Still, the indisputable quality of these films does little to hide the fact that they are as interested in delirium and asinine anthropomorphic equations as they are quiet truths. But does the animal exist outside of its propensity for being put in the perspective of human destinies and behaviours? And what if it were not a film star, and simply a living, breathing organism who drools, moves about, and sleeps? This, seemingly, is the question softly posed by Robert Bresson in the magisterial Au hasard Balthazar (1966).

The immense field of contemplative cinema offers elements of an answer. Replacing the psychologization and classical narration by an almost exclusively visual dramatization often leads to finding an exacting gaze and a distance deemed “respectable.” As if the camera (and all that stems from shooting) when pointed toward animals suddenly needed to find its perfect “intrusive humility.” When Artavazd Pelechian is at the controls in the overlooked masterpiece The Seasons (1975), he shows, with a quasi-lyrical brutality, the co-existence between Nature, Man, and the animals. Upon their backs and traversing a raging river, peasants haul sheep like they were sacks of sand. Never does the auteur add humanist or anthropomorphic intentions to this realism. The dignity of the work stems from the ease of filming things for what they are. Distance, like truth, is ensured. The shock provided by Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte (2010) partakes of the same dynamic. Doesn’t its unanimous success have something to do with its refusal to give a conscience other than a utilitarian one to its animal-protagonists?

Colder and more cerebral, the Austrian Nikolaus Geyrhalter is a master in this search for distance that solely resonates in the conscience of the viewer, who is busy seeking out perspectives and judgments that suit him. Falsely detached from everything, the scenes offered in 2005’s Our Daily Bread (the transportation of pigs toward an uncertain outcome; hundreds of chicks propelled from one conveyor belt to another; a dehumanized and mechanized collection of seed for over-vitamined cattle) seem to say that the filmmaker’s point of view, while certainly there somewhere, has but a very secondary value.

Recently, two films seem to have even further erased the moorings and point-of-views of their auteurs. The negation of narrative, a resistance to spectacle, and a willful abandon toward purely visual and sonic itineraries force the America of Sweetgrass (2009) to live at a time and pace of shepherds, ranchers and other modern-day cowboys. More anthropological than anthropomorphic, this elegy owes its beauty to not being accountable to anyone. At times too in search of beautiful images, France’s Emmanuel Gras reveals the nobility of cows in Bovines (2011). Just cows! And do not expect to see or find signs attempting to clarify the intentions around this quiet visual adventure, which borders on reverence.

My most recent film, Bestiaire, grazes in the latter pastures. To confine the narrative to a duel? To flirt with the observational documentary? I won’t announce my conversion to the Church of James Benning but I must admit that I worked in reaction to many things. In reaction to the literariness of my last film, Curling (2010). In reaction to whatever we consider trendy; in reaction to entertainment, to anthropomorphism, and the informational. More generally, I also tackle things “by negation,” by telling an actor not to do such and such things without revealing to him or her exactly what I want; by whispering to my DOP “everything except for that.” Thus, the idea of Bestiaire naturally came from a series of constraints, of refusals, perhaps even from the negation of the idea of subject matter itself.

Bestiaire is therefore everything except “that”; a that to be defined, formed, and deformed. Falsely naïve, the project proposed itself as a will to look, to show without telling. I communicated a clear desire to my small production team: I want the equivalent of a bestiary or a sort of book of decontextualized images, candid ones stripped of any easy or facile interpretation. In short, something primitive and rudimentary that would intrigue a four-year-old boy. That would be nice, no? But it’s precisely in the clash with the public, with hunters of meaning and the chasers of messages that the adventure is most exciting. Because it has been said that the work of an artist is to be aware of a certain order of things. But what do we make of organisms who live in the nude? How do we assess the order of things, without judging, when it is destined for the entertaining purposes of a zoo? The refusal of an inquiry or the inquiry of refusal, Bestiaire is docile like an animal. It waits to be watched, named, and placed within the confines where we want to place it.

Translated by Andréa Picard

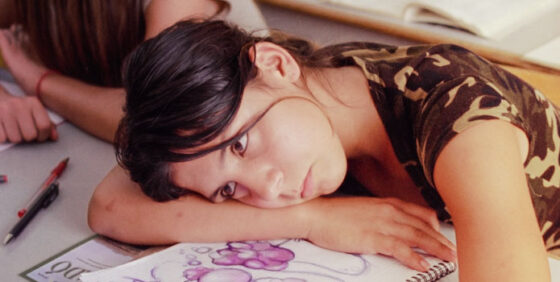

Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang (Laurent Cantet, France/Canada)—Special Presentation

By Kiva Reardon

Laurent Cantet’s Foxfire begins with a series of prophetic stills: flashing red lights at a railroad crossing, an empty small-town street, the halyard attached to an American flag creating an ominous noose-like loop, all of them pat but nicely turned signals that the eponymous collective is doomed from the outset. A badly adapted script soon bogs down the simple beauty of these images, however. The second adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ novel about a tough ’50s girl gang, Cantet’s version finds its young actors labouring over too-literary turns of tongue. Unlike the Jolie-fied 1996 version, Cantet’s film stays true to Oates’ original timeframe, setting the story up as a parallel history to the male greaser gangs of the era. The James Dean figures are conjured early on with the rival Viscount gang, but they remain on the periphery of the film, existing only as a distant counterpoint to the Foxfire girls. This is by far the film’s strongest move, subtly creating the illusion of two stories running at once: the one which has often been told, of young men railing against suburban malaise, and the alternate history of Foxfire’s distaff rage, but one that is targeted towards rapists and sexist authority figures. These wild ones are the rebels with a cause. But while Cantet’s previous work with young casts (i.e. The Class) managed to cannily create a convincing sense of verisimilitude, Foxfire never hits that same faux-realist mark. Encumbered by the script, the intriguing feminist issues raised stem solely from the Cantet’s source material rather than anything in the film itself.

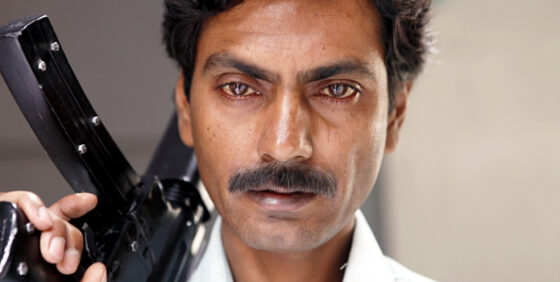

Gangs of Wasseypur (Anurag Kashyap, India)—City to City: Mumbai

By Michael Sicinski

A sprawling would-be epic spanning four decades and two separate feature films (the second was not available for preview), Gangs of Wasseypur swings for the fences and even hits on occasion. Essentially the multi-generational tale of a blood feud between two rival families in India’s coal-mining district, director Anurag Kashyap pulls no punches: he has sources like Coppola, Leone, and Bertolucci on his mind, filtered through his own specific approach to a new Indian cinema. As with his previous films Dev D (2009) and Black Friday (2007), his tactic is to channel the grit and rebelliousness of ’60s and ’70s Hindi cinema with a smattering of the old Bengali art-film high-mindedness. Kashyap’s own unique ingredient is a highly catholic approach to surface phenomena, employing slo-mo here and deep colour saturation there, for an overall Soderberghian ambiance by way of the cinéma du look. As you might expect, this tremulous, electric masala adds up to a little bit less than the sum of its parts, if only because Kashyap too often has trouble meaningfully articulating the disparate elements. The eventual revenge battle between Sardar Khan (Manoj Bajpal), a mid-caste cad, and Ramadhir Singh (Tigmanshu Dhulia), the industrialist who killed Khan’s father, simply can’t bear the weight of everything Wasseypur has riding on it. While consistently diverting—more American Gangster than Once Upon a Time in the Dhanbad—the attempts to thread this mafia tale into a macrocosm for post-colonial rapacity don’t completely convince. Gangs of Wasseypur aims to show where present-day outlaw capitalism in India came from, a tall order indeed. That Kashyap delivers only mitigated results is no disgrace.

Just the Wind (Bence Fliegauf, Hungary/Germany/France)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Boris Nelepo

Just the Wind opens with a title card stating that a few years ago in Hungary several Roma families were murdered, and that the film is not a documentary but rather an attempt to recreate those frightening events. After such a disturbing introduction, a tragic ending is inevitable; apparently, this is meant to deepen the emotional immersion into the everyday life of a small Roma family, indistinguishable (on the big screen at least) from that of any other oppressed and humble peoples in this world. For director Bence Fliegauf, it is no obvious fact that violence in itself is an incomprehensible abyss, terrifying to behold. As a result, he chose to film an extremely straightforward statement, portraying the main characters as wholesome to a fault. In spite of the xenophobic stereotypes about lazy Gypsies, the mother of the family is wearing herself out in a humiliating work situation, all the while caring for her paralyzed father, and the kids are top-notch students and thoughtful explorers of the surrounding world.

Where Womb, Fliegauf’s previous film, resembled a student work in its naïve depictive approach, Just the Wind imitates the much admired indie-movie aesthetic, with its minimal dialogue, reserved performances, and the sunlight streaming into the lens—all of which makes its exploitation of this subject seem all the more cynical. Even the touching scenes of the boy walking through the forest cannot breathe life into the vacuities constituting the film. The fact that the calculated, directed murder taking place onscreen represents the actual death of real people seems to have only one effect: to make the viewers ashamed of checking their watches as they drearily wait for the impending finale.

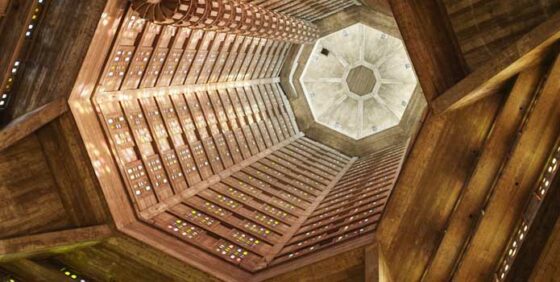

Perret in France and Algeria (Heinz Emigholz, Germany)—Wavelengths

By Mark Peranson

Heinz Emigholz’s groundbreaking and spellbinding architectural films are, quite simply, cinematographic re-enactments of the immediate experience of spaces. With an often canted camera, he dissects the interior and exterior of a building, allowing the viewer to experience being there and, by studying a career of an architect, construct a biography solely based on the works, free of commentary. The last film in Emigholz’s Architecture as Autobiography series to focus on a specific architect, and the second in his series “The Decampment of Modernism” (following the equally excellent Parabeton, which premiered earlier this year in Berlin, and has gone on to become a surprise box-office hit in Germany), is the first film ever made on French brothers Auguste and Gustave Perret, presenting 30 of their projects in chronological order. And it may be perfect. (Emigholz himself considers it to be his finest film.)

Like Emigholz’s other subjects—Goff, Maillart, Loos, Kiesler, Schindler, Sullivan—Auguste Perret was an architect’s architect whose sublime structures, ranging from stunning churches lined with stained-glass windows, private homes, and public commissions, achieved sensational results with an unusual combination of stylistic elements from Art Nouveau and neoclassicism with externalized construction frames and bold experiments with concrete, especially in stairwells. As in Parabeton, which presents works from Italian Pier Luigi Nervi alongside Roman ruins, Perret presents a delicious juxtaposition between projects in France (up to the landmark postwar reconstruction of Le Havre) and public buildings built in Algeria, then under French colonial rule. More than ever, Emigholz places the buildings (erected between 1904 and 1954) in their contemporary social conditions; the result is a portrait of France and Algeria in the year 2011.

Pusher (Luis Prieto, UK)—Vanguard

By John Semley

Maybe it’s unfair to regard a film in light of festival programme book copy, which is, by its very nature, bogusly trumped up. But TIFF’s note on Luis Prieto’s unnecessary remake of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Pusher (1996) rings as especially hilarious, bothering to mention that Refn not only executive produced the remake but “gave Pietro his full blessing”! No mere relicensing of Refn’s diamond-hard Danish blockbuster (already treated to a 2010 Hindi adaptation), Prieto’s Pusher has been sanctified by the director of Drive (2011) himself! Accept no substitutes for this superfluous substitute.

Keeping pace with Refn’s original, Pusher follows a particularly hectic week in the life of London drug dealer Frank (Richard Coyle) as he scrambles to muster £55,000 to pay back captivatingly psychotic greaseball crime lord Milos (Zlatko Burić, on loan from Refn’s original trilogy, and pulling off a persuasively amped-up impression of his original character). For anyone familiar with Refn’s original—which is extremely popular globally, despite non-Danes having to suffer through damnable subtitles—this Pusher feels like a well-worn recitation. There are a few welcome performances, including turns by Kill List’s Neil Maskell and It’s All Gone Pete Tong’s Paul Kaye, but otherwise the film is entirely by the numbers. Worse, Prieto can’t even credibly sustain Refn’s tense, crackerjack pacing, lingering too frequently on shots of Coyle’s doomed, droopy mug.

In a way, exporting Pusher to a UK context seems like an act of repatriation. After all, Refn’s picture borrowed heavily from British crime films of the ’70s, ’80s, and early ’90s in its depiction of a gentler criminal underground, where violence was tempered by a fuzzy sense of European civility, essentially anticipating the films of someone like Guy Ritchie. Prieto’s film feels too late to the party, its scenes of strobe-lit club decadence conjuring flashbacks to Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), from which it also nips a transsexual panic “joke.” At 87 minutes, it’s mostly fleet and fast enough to create the sensation of entertainment, but beyond being literally borrowed from its superior source text, its action and atmospherics feel old-hat even by imitative Brit-crime standards.

The Reluctant Fundamentalist (Mira Nair, India/Pakistan/USA)—Gala Presentation

By Christoph Huber

(Note: to accurately represent the wretchedness of this “world cinema” experience, the following review has been written in German and babelfished, with only the most necessary edits applied.)

The Reluctant Fundamentalist follows Changez Khan (handsome British hip-hopper and actor Riz Khan, but embodies colorless) and his American dream: a native Pakistani, Changez studied at Princeton and then experiences a steep climb as analyst for a New York business consultant company. Through tough calculations Changez becomes the darling of his superiors (cliché, but good: Kiefer Sutherland). Until 9/11, everything changes: Changez is degraded victim of checks and suspicions, soon he finds his car with slashed tires. The redneck offender drives past and shouts “Fuck you, Osama!” Mira Nair’s plea for differentiation, performed with the mallet. The viewer granted so little acumen as the one-dimensional representatives of brutal capitalism and Islamic fundamentalism, which are equated as antagonistic. A conversation provides the frame story: Changez disappointed, as “revolutionary” university lecturer returned home, telling his story to a US reporter (Liev Schreiber is struggling with an underdeveloped role), secretly working for the terrorist fighters. Street battles outside and exalted flashbacks provide artificial excitement in the sluggish dramaturgy, while Nair jumps between the living Lahore and the oh-so-soulless office worlds of New York until politics is ultimately sacrificed the strictly personal. As in revenge films, but here, ironically, in the name of a vague humanism that can’t hurt anyone: fundamentalism evil, peaceful understanding well. The film has something of a moment of truth: Changez finds a friend in the traumatized niece of his boss. Played by a brown-haired Kate Hudson unconvincing, she emerges as an artist whose installations are abysmal (which the filmmakers seem to be unaware). When turning her relationship with Changez into a dripping of embarrassing platitudes, he has finally had enough—and the audience gets a good metaphor for the film itself. Self-irony seems, unfortunately not in the game. If only Bobcat Goldthwait directed.

Rust and Bone (Jacques Audiard, France/Belgium)—Special Presentation

By Richard Porton

Jacques Audiard no doubt believes that his crowd-pleasing films combine the best elements of genre cinema and art-house sophistication. For at least a vocal group of naysayers, however, they synthesize the worst of both worlds: the generic aspects of the films are usually much flatter and more formulaic than decent popular cinema, while the “art-house” components just end up seeming like pretentious aesthetic filigree. Whereas Audiard’s prize-laden Un prophète (2009) was an unsatisfying prison film pastiche, his latest is a bombastic reinvention of the melodramatic imagination.

Although I haven’t read the Craig Davidson short story that Audiard Gallicizes (or, according to the credits, was “inspired by”), it’s doubtful that the source material is as ploddingly schematic as the movie. The narrative’s trajectory is set in motion when Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), a bouncer and con artist who scrapes by while illicitly installing surveillance cameras in local businesses, encounters Stephanie (Marion Cotillard) at a nightclub and prevents her from being mauled by some moronic bruisers. Meeting cute, this clichéd beauty-and-beast pairing cannot, quite predictably, help falling in love. When Stephanie, who trains killer whales for a living, loses both her legs in a horrific accident, it’s not being insensitive to report that she and her paramour’s sex life receives an unexpected boost. These supposedly erotic sequences are probably designed to move the melodrama to a visceral level, as is Stephanie’s use of the B-52s’ “Love Shack” as a morale booster while she languishes in her wheelchair. Yet Peter Debruge’s Variety review provides an unintentional glimpse of the unbearable nature of Audiard’s stab at aesthetic frisson. Debruge observes that “(L)ike Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler a few years back, Rust and Bone blends Dardennes-esque naturalism…with more conventional plotting and compositions.” The last thing we need is the sort of Frankenstein monster that results when a sloppy emulation of the Dardennes is crossed with sexed-up versions of the hoariest plot twists in film history.

cscope2