TIFF Day 2: Arirang / This Is Not a Film / Almayer’s Folly / The Descendants / Generation P / The River Used to Be a Man / Shame / The Snows of Kilimanjaro / Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale

Arirang (Kim Ki Duk, South Korea)—Real to Reel

This Is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, Iran)—Masters

By Mark Peranson

By Mark Peranson

An amateurishly shot “self-interrogation,” the Cannes Un Certain Regard-winning film Arirang is cannon fodder for the enemies of director Kim Ki Duk, and of those the director rightly claims there are many; there should be even more after Arirang sees the light. For three years, the filmmaker has been living in self-imposed exile inside a tent squeezed into a tiny cabin. This is, in short, what we see director Kim Ki Duk doing for the better part of Arirang: washing himself, making food, eating food out of a dog bowl, talking to his cat, doing nothing, brushing his hair, watching TV, stoking the fire, roasting and eating nuts, staring into the distance, brushing his teeth, drinking soju, doing nothing, operating a backhoe, making espresso, eating a tomato, and ceaselessly bitching like there’s no tomorrow. And, how could I forget, singing.

For it seems that “director Kim Ki Duk”—as he addresses himself on occasion—has been experiencing something like a “director’s block” for the last three years, his exile stemming from a combination of a John Landis complex following the near-death of an actor on the set of Dream (2008), and being stabbed in the back by a former assistant. Like I care. Unlike the banned Jafar Panahi, Kim’s retreat from filmmaking is ultimately a luxury; yet spurred on by the need to explain this gap to his many fans, Kim films himself on his consumer Canon Mark II digital camera to understand himself “as a director and as a human being.” Much insufferable bloviation ensues about how he became a world-famous film director (even in Israel!), how he wants to work in different countries, how he misses film festivals—all of them!—as they gave him a chance to be understood in Korea, where otherwise he’d just be a box-office failure.

The worst—well, relatively speaking—is that Kim thinks he can get away with off-the-top-of-his-head ramblings by throwing in a veil of “fiction.” He inserts a framing device of himself watching himself watching himself—telling himself, “You think too much!” and even laughing at himself crying what are likely real tears, as he endures the climax of Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring (2003)—to make it painfully obvious that the real director Kim Ki Duk is conscious that what he’s doing is incredibly embarrassing, and that his new cinematic counterpart’s bald-faced bitching is coming across as self-absorbed and paranoiac. And if that wasn’t enough, he proceeds to act out a climactic serial-killing montage, wielding a gun with a little Buddha on the handle that he fashioned himself. (I prefer his self-made espresso machine.) If the whole thing is “fiction,” then perhaps it is genius; but as the numerous film posters he flashes on screen remind us, director Kim Ki Duk is of course truly incapable of genius, so we can conclude that he means most of what he’s saying.

This is not to say that Arirang is completely bereft of value. Director Kim Ki Duk presents one of those delicious occasions for reading metaphors for film festivals in his own elaborate philosophy (to use the term generously) of life, grounded in the fact that to survive, humans must kill animals and plants for sustenance: “sadism, self-torture, and masochism. Torturing others, getting tortured, and torturing oneself.” Eventually, director Kim Ki Duk surmises, most people settle for self-torture, though his filmmaking career bears evidence of a desire to encompass all variations of pain infliction, something he truly accomplishes over the course of Arirang. To this degree, a generous and patient viewer—or a jury chaired by Emir Kusturica—might consider the film a conceptual success. As might those who harbour an animosity for the Korean film industry. But this ultimately is not a film: it’s a waste of time, and any place that would even play this load of garbage doesn’t deserve to be called a film festival.

But seriously folks, Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb’s unimpeachable This Is Not a Film—perhaps the closest Khavn de la Cruz will get to Cannes—is an absorbing, fascinating, and slyly complex portrayal of the Iranian director at home, living his daily life, and delivering a master class on how to make a film without making a film. (The closing credits modestly—and legally—identify the work as “an effort,” which would make Arirang “a joke.”) Everything that director Kim Ki Duk does wrong—which is literally everything—Panahi does right. Always comfortable in front of the camera, despite periodically protesting his distaste for the scenes that are being and have been shot, Panahi is totally bereft of arrogance. He illustrates his grander points—which have more to do with filmmaking in general than the specific place in life he finds himself—through mise en scène, not flatly declaring them to the camera like director Kim Ki Duk. The work feels completely effortless, but my money says it’s an elaborate sound and image construction: though it claims to be a day in the life of Panahi, Mirtahmasb (recently snatched at the airport in Tehran while en route to TIFF) explained in interviews that the film was shot over four days.

This Is Not a Film proves that even if a political entity tries to take the power of filmmaking—or film festivalling—away from a director, there’s nothing that can be done if that filmmaker possesses creativity, dedication, skill, and intelligence. The comparisons with Arirang are obvious. Panahi is a filmmaker whose internal exile is a result of a 20-year government ban from travel and filmmaking; he can’t leave Iran, and spent a long period under house arrest. Though he’s presently free to travel within his country’s borders, all of This Is Not a Film takes place in his apartment as he awaits news of his appeal, doing daily tasks like preparing breakfast, speaking to his attorney and supporters (such as director Rakshan Bani-Etemad) on his iPhone, watching the Japanese tsunami on television. To quote again director Kim Ki Duk: “I can’t make a film so I’m filming me. My life is a documentary and a drama. I think films are the truth…there’s no need for lighting or fancy cameras.” Over the course of the not-a-film, Panahi’s main company, besides the video camera—he is reluctant to turn it on or touch it himself, as a way of ensuring he does not break the ban on “filmmaking”—is Igi, his daughter’s rather large iguana, whose roaming throughout the apartment, creeping up Panahi’s body and ending up on the walls behind the bookshelves, serves as a deliciously ironic parallel to Panahi’s own mental and physical state. (Some other priceless comedic bits involve a yapping dog belonging to his neighbour, who unsuccessfully attempts to saddle Panahi with the pet.) Eventually Mirtahmasb shows up, claiming to be making “a behind-the-scenes film about Iranian directors not making films,” and the real film within the not-a-film begins.

Panahi launches into something of a lecture on directing non-professionals, contending that in his kind of filmmaking, the director is never fully responsible for the content of his film. He illustrates this point with a memorable clip from The Mirror (1997), wherein the young “actress” removes a cast from her arm and stops acting, walking off camera—where she is of course filmed by another camera. (Of special note in this scene is Panahi’s bootleg DVD collection, which features the Ryan Reynolds-in-a-coffin film Buried [2010] facing us, clearly placed there to make a point.) On the surface, Panahi’s professed identification with his young star speaks to his sense that he is just marking time by making this not-a-film, which he constantly degrades over the course of the too-brief 75 minutes. But, on a deeper level, what Panahi does over the course of the not-a-film is behave as an actor, controlling the image as much as when he is holding the camera—which, of course, he is not allowed to do.

Panahi then begins to read from a screenplay of the film he was preparing to shoot (and had already cast) before running afoul of the law, the story of a girl from a traditional family admitted to study in an arts university against the wishes of her parents, who lock her in their house when they leave on a trip. (Indeed, director Kim Ki Duk also relates the story of a film he planned to make, about a US soldier who fought in the Korean War and returns 50 years later to find the body of a man he killed; it sounds awful.) The entirety of Panahi’s unmade film was to take place—like the one we are in the process of watching—inside of a house. (He had never shot interiors before, he mentions, because of the cultural taboo surrounding the need for so-called women’s modesty.) Panahi thus skirts the ban by reading and acting out a screenplay that has already been written, taping lines on his carpet to erect a floor plan of the interior he would have filmed, and “dressing the set,” unconsciously bringing to mind the design of none other than Lars von Trier’s Dogville (2003). (Or is it conscious?) He abruptly stops, overcome by the realization that telling a film and making a film are not, and can never be, the same thing. “If we could tell a film, then why make a film?” Or, indeed, why write about one?

Over the course of his narration—starting even earlier in the afternoon—we hear what sounds like ominous gunshots or explosions on the soundtrack, booms about as jarring as anything Gaspar Noé could conceive of. Panahi is seen looking out the window in curiosity, eventually “filming” on his iPhone 4G what we are led to think are political protests, or the suppression thereof. Only late in the game—as what Panahi is playing is an elaborate game, not only with the regime but also with his audience—are we told courtesy of the television that it’s actually Fireworks Wednesday, the celebration of the coming Persian New Year, and these booms and cracks are in fact celebratory explosives. Still the political situation remains dicey, as Panahi learns from a phone call from a friend in his car who relates how he was stopped by the police and asked what he was doing with the camera on the seat beside him.

But before then, the film has taken another detour, one which sees Panahi finding a perfect balance between relating his personal tragedy and creating art out of it. Following a second illustration of his own filmmaking philosophy via a clip from (the Wellspring DVD of) Crimson Gold (2003), Mirtahmasb leaves, but not before imploring Panahi to leave the camera on, as the main thing is the need to document (implying that what we are seeing is a mere document, when that’s far from the case). Enter the door-to-door trashman, actually a college student “substituting” for a relative, who wonders why Panahi is shooting on an iPhone when there’s a real camera sitting in the kitchen. Panahi then picks up the camera for the first time and follows the almost too-telegenic collector along his route, down the elevator, as the kid reveals he was in the building the night the police raided Panahi’s apartment and arrested him. The student never gets to finish his story recounting the events of that evening, as it’s constantly interrupted by stops to pick up trash, another encounter with that yapping dog, and so on. Eventually Panahi interrupts this surely planned-out set piece, telling him that the story isn’t important; what matters, we’ve come to understand, is the filming. At last venturing outdoors, Panahi comes across the streets of fire, celebrations and yelling that might also be a glance into hell—the last intrusion of the real and hopefully not the last image he will ever film.

(Excerpted from “This Is Not a Film Festival,” Cinema Scope 47.)

Almayer’s Folly (Chantal Akerman, Belgium/France)—Masters

By Gabe Klinger

By Gabe Klinger

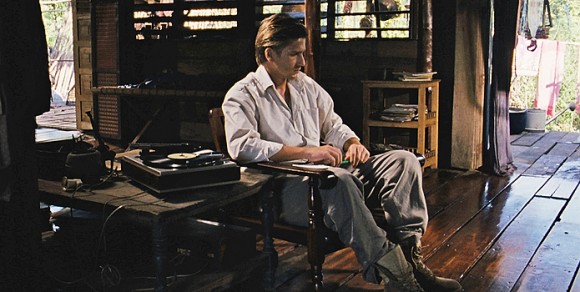

Liberally adapted from Joseph Conrad’s first novel, Almayer’s Folly is Chantal Akerman’s most satisfying fictional feature since La captive. Like that earlier film, which mined from Proust, it boils down its richly detailed source to a few austere gestures that balance the cross-cultural impulse of her recent documentary work (De l’autre côté comes to mind) with her better-known European narratives. There’s not much in the way of plot, but rather a lot of emotive intensity in the mise en scène that suggests, while at the same time eluding, the deeper literary structure of Conrad’s story.

Taking place in the present day—although the recurring use of Tristan and Isolde on the soundtrack suggests a 19th-century setting—Almayer’s Folly focuses largely on the title figure (played by a droopy-faced Stanislas Merhar), a European trader in Southeast Asia haunted by his past failures. At the beginning of the film, we see a woman named Nina (newcomer Aurora Marion) mourning the death her lover, Dain (Zac Andrianasolo), who’s knifed while miming a Dean Martin song onstage in a bar. Nina, as it turns out, is Almayer’s daughter, who as we learn over the course of the film has suffered much disillusionment caused by her father, eventually leading her to run away with Dain.

Akerman shot on location in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, although the setting, like the time, is only a minor part of its spare construction. (The characters make reference to their being in Malaysia, where Conrad’s novel was set.) Avoiding touristic or conventionally beautiful views to instead focus on a landscape of shiny, floating bodies (Marion’s is particularly pleasing), Almayer’s Folly powerfully confirms John Ford’s maxim that the most interesting thing in the world is the human face. Akerman has invoked Murnau in the press notes, and the film certainly captures something of the wistful opulence of Tabu, while also suggesting Joseph Cornell’s avant-garde masterpiece Rose Hobart in the way it presents lost glances, fleeting movements, and deliberately slowed-down environments.

The Descendants (Alexander Payne, US)—Special Presentations

By John Semley

By John Semley

Looks like Alexander Payne is over being glib. Maybe he’s outgrown it? Whatever the case, The Descendants may be his best film since Election, if only because it evinces a confidence to dabble in emotion and sentiment without pulling back into the stilted, familiar territory of Payne’s Middle-American satirizing. Clooney pulls off his smirking salt-and-pepper shtick again, but unlike the tedious and haughty Up in the Air, he seems to shed something other than crocodile tears. He’s believable and, better, compromised, even a bit pudgy. The empathy Clooney’s Matt King commands is especially impressive considering that his character is a rich Hawaiian real-estate attorney whose bloodline trickles back to Kamehameha the Great. But faced by a typically Paynean predicament—his wife, who’s trapped in a coma she won’t come out of, was fucking around on him—Clooney shoulders it all with a convincingly dopey grace that never lapses into schmaltz, though with all the puffy eyelids and misty cross-fades it occasionally teeters precariously on the edge.

More than seeming mature, The Descendants is funny, in that pithy way Payne’s films have always been funny. (“Witty,” you’re supposed to call them, right?) Robert Forster turns in a pitch-perfect performance as Clooney’s cantankerous father-in-law, ditto Beau Bridges as Clooney’s laidback cousin, doing an appropriately in-the-family impression of The Big Lebowski’s Dude. Though at times frustrating in its propensity to give all its characters the faculties and opportunities to make all the right choices, The Descendants is Payne’s first film to hustle for its own sense of self-admiration.

Generation P (Victor Ginzburg, Russia/USA)—Vanguard

By John Semley

By John Semley

Though it owes plenty to Bruce Robinson’s How to Get Ahead in Advertising and the psychoanalytical PR propaganda theories of Freud’s wily nephew,Edward Bernays, there’s a great deal of energy and originality in Generation P, a pitch-black send-up of the post-Soviet mentality spanning from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the present. Vladimir Yepifantsev plays Babylen, a would-be man of letters working for some exacting Chechens in the wake of the Cold War, selling Coca-Cola and Marlboros to a Russian populace craving the spoils of imported imperialism. He soon winds up working as a copywriter for an old friend, exhibiting a canny aptitude for laconic copy and, more importantly, a through-line to the collective unconscious of a Russia at once in love and at war with the emerging capitalist ideology. His savvy for speaking to the people by defining how they want to be spoken to lands him a job sculpting digital politicians and virtually staging the day-to-day goings-on of Russian political life (his greatest achievement: a Putinesque populist tyrant cheerily responding to Russia’s fear of democracy).

As time passes, capitalism spreads, and our hero’s downy mullet (which distinctly recalls Roddy Piper’s flowing locks in They Live) recedes into a slicked-back executive haircut, Babylen’s role in sculpting an increasing ersatz post-Soviet state deepens. Lenin once cracked (in a definitive piece of Marxian pith) that it’s in the nature of the capitalist to sell the rope with which he is hung. As an American co-production awash with the logos and names of real brands, Generation P sheds only crocodile tears for the dizzying perils of late-stage, globalized laissez-faire capitalism. Ginzburg offers some smart, inventive satire, but he’s too clearly enamoured with the pillage-and-plunder of the Pepsi Generation to string anyone up.

The River Used to Be a Man (Jan Zabeil, Germany)—Visions

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

Actually the river here is not a man, but a metaphor for an outsider’s attempted immersion in a different culture. If that makes Jan Zabeil’s debut feature sound poetic, that’s because the filmmaker is straining very hard in that direction, but ultimately all that The River Used to Be a Man really serves to illustrate is its maker’s transparent ambitions. There’s a fine line between “contemplative” cinema and boring cinema, and there isn’t much to contemplate here. From the moment our blonde, blank-faced protagonist (Alexander Fehling from Inglourious Basterds) arrives on the Dark Continent, it’s clear he’s an outsider and in need of having his status pointed out to him (and to us) by an indigenous sage. Having served his purpose, this character—who had been acting in a highly symbolic capacity as the visitor’s ferryman—quickly dies and is transformed into another symbol: a literal white man’s burden, conscientiously lugged downstream back towards his son who will of course not take kindly to having a corpse delivered by a strange German guy. The heaviness of these devices might have been alleviated by some terrific filmmaking, but Zabeil gives the proceedings a deadly pace: imagine the floating atmosphere of Los Muertos minus Lisandro Alonso’s mesmeric sensibility and you’ve got it. The River Used to Be a Man isn’t mesmeric but soporific, overdoing the shots of Fehling bobbing along, staring into the middle distance. By the end, we know how he feels. That old saying about still waters running deep doesn’t apply here.

Shame (Steve McQueen, UK)—Special Presentations

By Jay Kuehner

By Jay Kuehner

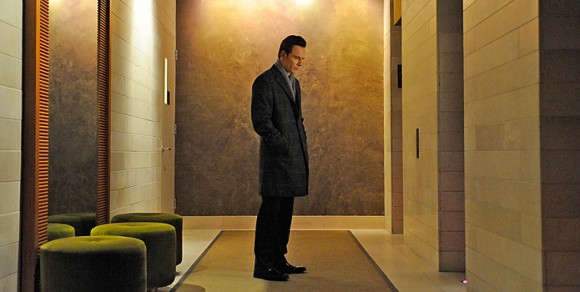

When it comes to shame it seems that the problem is always one of excess: either there is too little or too much. In the case of Steve McQueen’s titularly cool construct (begun with Hunger, and now Shame, a continuum of films on the human condition now appears imminent), the issue is embodied by Michael Fassbender’s alternately seductive/repulsive mid-town office crony Brandon, tightly wrapped in overcoat and scarf or stripped to his taut core, chronically masturbating at work by day or pinning hookers to the glass window of his chrome-blue condo at night. Indeed, Fassbender’s Brandon is a real coil, tightly wound and poised to pounce or shrinking back into his own ineffable mystery.

McQueen calculates Brandon’s enigma with careful precision, keyed both to the sheer viscera of his desire and the contrasting inanimate environment, the two no doubt causally related. The drama, announced by Harry Escott’s shimmering score, unfolds beyond the blue-linen bed in the hyper-tedium of office cubicles, designer bars, and subway cars, arenas in which Brandon’s escalating or diminishing condition (McQueen teases the question) finds satisfaction or frustration, or as is the case with compulsion, both. One repeat sequence sees him staring down a cute girl on the subway, at once charming and creepy, only to watch his object of desire disappear on the platform. If the game represents a perfect fantasy of possession and its impossibility of fulfillment—a kind of eureka for the addict—a less ideal portrait is drawn by McQueen’s striking image of Brandon seen from behind against a drab backdrop of closed blinds, slumped over as to appear headless, a hulking container of grief.

The source of Brandon’s pain is left undisclosed, his past conjured only by the arrival of a baby sister (Carey Mulligan) who suffers outwardly (and sleeps with his pathetic, but normal by contrast, boss) and becomes a “parasite” to him. What, however, can she draw from such a pulsing but hollow well? The cure, it seems, entails tossing out the porn and going on a real date, a gesture that serves to confront Brandon with the extent of his own poverty. That anyone should feel a measure of sympathy or antipathy towards him might reflect one’s own experience of the insidious emotion of McQueen’s choosing, which may well be the film’s point. To ratchet the drama to tragic proportions, however, misses the implicit tragedy that poor Brandon may be more of a common man than we care to admit.

The Snows of Kilimanjaro (Robert Guédiguian, France)—Masters

By Tom Charity

By Tom Charity

Nothing to do with Hemingway, this drama of conscience is firmly rooted in Robert Guédiguian’s familiar Marseille neighbourhood. Jean-Pierre Darroussin is Michel, a veteran trade unionist who pulls his own name out of the hat when the men draw lots for forced redundancies. Friends and family rally round and come up with enough money to take Michel and his wife Marie-Claire (Ariane Ascaride) on holiday to Africa, but their plans are derailed when two masked men break in, tie them up and make off with the cash. Michel recognizes one of the assailants—but can a good socialist condemn a poor man for doing what he must to provide for his loved ones?

Inspired by Victor Hugo’s poem “How Good Are the Poor?” (no better than they can afford to be, evidently), Guédiguian’s film also brings to mind that old chestnut: a liberal is a conservative who hasn’t been mugged yet. Michel bucks that stereotype, but alienates his friends in doing so. While he’s hardly breaking new ground, Guédiguian comes up with a couple of unexpected plot developments, and the trauma and tension in the immediate aftermath of the crime ring true, even if the film is ultimately too contrived and pulls some (though not all) of its punches. (The best is a left-field running gag involving Marie-Claire and a philosophical waiter who knows how to cheer her up.) Aging lefties may feel equally grateful for the filmmaker’s warming cocktail of sentiment and melodrama.

Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale (Wei Te-Sheng, Taiwan)—Special Presentations

By Shelly Kraicer

By Shelly Kraicer

The most expensive film in the history of Taiwanese cinema, Seediq Bale is a major cinematic event. Director Wei Te-sheng based his 270-minute Taiwanese aboriginal epic on an extraordinary though little-known historical event. During the fifty-year-long Japanese occupation of Taiwan, the remnants of the aboriginal tribes who first settled the island lived in the central Taiwanese mountains. The Japanese colonial government restricted these tribes from practicing their traditional headhunting and facial tattooing, and deprived them of their lands and weapons. An uneasy peace came to a crisis point when tribal leader Mouna Rudo, a “hero of the tribe” (Seediq Bale), organized six villages of the Seediq tribe to attack the Japanese occupation police on October 27, 1930 in Wushe village. Their carefully planned and executed rebellion resulted in the deaths of 136 Japanese men and women. The rebellion lasted for fifty days, as Japan sent police and army reinforcements to crush the aboriginal fighters, eventually resorting to dropping poison gas on the rebels from the air. The rebellion took on the aspect of a 20th-century Trojan siege: Seediq heroes fought to the death, while their family members were instructed to commit suicide in order to escape capture and humiliation.

Wei Te-sheng’s film of the Seediqs’ heroic resistance doesn’t shy away from the violence, the darkness, and the moral ambiguity of the story. The sometimes self-destructive ferocity of the Seediq warriors is balanced against fascinating characterizations of the Japanese policemen caught in the middle, who knew both Seediq culture and their homeland’s militarized culture. Seediq Bale is true epic cinema: thousands of extras, large-scale battle scenes shot against the lush forests and mountains of central Taiwan, a multi-generational time span, and larger-than-life heroes create an unforgettable picture of a little-known society’s life and death struggle to preserve their environment, their beliefs, and their values.

cscope2