TIFF Day 1: City to City: Buenos Aires / The Boy Who Was a King / Duch: Master of the Forges of Hell / Hard Core Logo II / Hors Satan / The Last Christeros / Lipstikka / A Mysterious World / Nuit #1 / The Other Side of Sleep / Restless / The Sword Identity / We Need to Talk About Kevin

Cinema Scope 48 Preview: City Sisters: Buenos Aires in the Spotlight at TIFF

By Quintín

By Quintín

One of my town’s most remarkable landmarks is a really awful globe made of concrete that sits on Main Street. It was donated by the local Rotary Club in association with some California branch of the institution. The reason for the existence of what charitably can be called “a statue” is that my town is called San Clemente, like the California resort of 60,000 where Richard Nixon established his summer residence. San Clemente, Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina, is also a resort, only smaller (15,000) and much poorer, but still a dotted line joins the two places, considered to be ciudades hermanas.

I thought about this curiosity when I learned that this year the Toronto International Film Festival chose Buenos Aires to be its de facto sister city for the City to City program. In principle, it smelled as paternalistic as the Rotary fiasco. But after reading the essay in the festival’s catalogue, I concluded it was somehow worse.

That rave about Buenos Aires and its cultural and film life manages to reunite all the traits of propaganda that are found in a tourism brochure. It’s also painful to read about the “explosive urbanization process” in a city where housing is a big problem and urbanization takes place mostly through the growth of shantytowns. The authors of the piece overstress their goodwill, and in doing so present the country, the city, and the film scene as the authorities would like them to be portrayed. When you say things like “a city of café culture, rabid soccer fans, cosmopolitan chic and, of course, tango,” you’re not only entering the realm of cliché but you’re also on the path to colonialism, which starts when the guy from the rich country looks in the eyes of the guy from the poor country and says, “How much I like your people and your land!” The next step is to take the land. In this case, taking the land means directing a superficial glance at the local film scene and making it part of the big festival from the big country, like some wild animal turned into a circus attraction.

Yes, there is a film scene in Argentina, and it is based in Buenos Aires. But this is not exactly an asset: Buenos Aires is a massive city that concentrates the population and especially the wealth of the country, but any local filmmaker would say that one of the drawbacks of this situation is that since the silent era, there have been very few films made in Argentina outside of Buenos Aires. Only recently have things begun to change—among a few others, Lucrecia Martel’s movies made in her hometown Salta are the proof that the absolute dominance of Buenos Aires is coming to an end. In any case, it’s fair to choose films made in Buenos Aires or elsewhere and show them to the Toronto audiences: that’s what festivals are about. Also, the choice cannot be as controversial as that of 2009, when Tel Aviv was chosen for the first City to City program. (Fortunately, there is no civil war in Buenos Aires, only the Kirchners.) And yes, starting in the late ‘90s, the film industry has grown consistently in terms of production and prestige (more so than in box office), leading to arthouse films that have won many festival awards, and mainstream films, including The Secret in Her Eyes (2009), which won Argentina’s second Foreign Language Oscar. Although I wouldn’t talk about a proliferation of auteurs or call the situation “a hub of creativity,” neither am I sure that there is at present “a vast reservoir of talent” or a “diverse, passionate artistic community” that is big enough to be showcased.

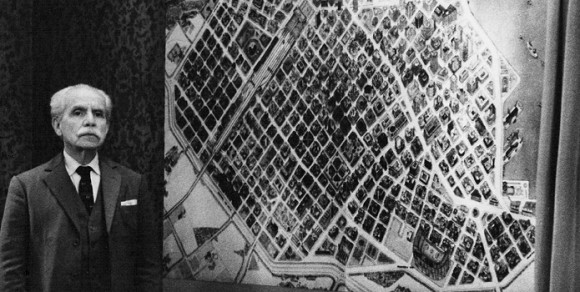

Even so, one of the more clever decisions by the CTC programmers was to start, historically speaking, with a very radical film made in a different time. Invasión (1969) was directed by Hugo Santiago, one of the few Argentine filmmakers who could be considered not only a master of his trade but also a fully cultivated person, and co-scripted by Jorge Luis Borges, the only attempt by the writer to work in the film business. Exquisitely shot by Ricardo Aranovich, Invasión is a kind of noir allegory that remained invisible for three decades, and is essentially unknown to North American audiences. Only a recently discovered French print allowed the film to re-emerge and prove that its cult status is absolutely deserved. (It’s also screening at the New York Film Festival.) Invasión is also Buenos Aires to the flesh and bone, even if the city is disguised as an abstract mythological place named Aquilea. Like a Western, the film is focused on the resistance of a reduced group of heroes, the last to oppose a terrible but gloomy totalitarian force that is slowly taking over the country. Through the years, the meaning of this confrontation has been interpreted in several ways; there isn’t a clear answer to this enigma. But recently something new occurred: the resistance has been interpreted by young filmmakers as being that of art against commercialism. Invasión has become not only a landmark in Argentinean film history, but also serves as a model. A number of recent films are inspired or influenced by Invasión, and at least three of them—Castro (2009) by Alejo Moguillansky, Las pistas (2010) by Sebastián Lingiardi, and La carrera del animal by Nicolás Grosso—pay an explicit homage to Santiago to the point of partially cloning the plot and the atmosphere.

It’s also a good choice to show Crane World (1999) by Pablo Trapero, one of the true talents of his generation. Crane World is his first film, and marks a crucial moment in the rise of the New Argentinean Cinema. It opened at the first edition of the Buenos Aires Film Festival (BAFICI) and was maybe the first example of an outstanding movie made by a film-school graduate working with very limited money, no support from INCAA (the government-run film board, where the committees always fund the established producers), non-professional actors, a crew recruited at the film school, and a film going against the grain of the local mainstream. With a loose plot and a very subtle approach behind a neorealist surface, Crane World not only portrays the material and spiritual results of the economic crisis of the last 30 years in the country, but it’s Trapero’s first of many attempts to film the process of “learning” (in chronological order, his films have been about learning in the areas of manual work, the police, travel, isolation, jail, and the mafia). But Trapero is also important because his career has slowly evolved from the marginal position from which he made Crane World to a director of international mainstream cinema, as proved by Carancho (2010), his last film. Trapero’s evolution—he is now also a medium-sized producer—is parallel with the growth of Argentinean cinema as a whole, in terms of state and private financing. Thanks to easier conditions for filmmaking, quite a few of his contemporaries are making films on a regular basis with private money, but very few can still be thought of as auteurs, as Trapero always has been. (Speaking of history, I think the programmers missed the chance to show one of Fernando Solanas’ films, not only because of the importance of the filmmaker, but because he just ran for mayor of Buenos Aires—and lost).

The rest of the material is from this year and, as a whole, is not as justified as the two historical pieces. I haven’t seen Carlos Sorín’s The Cat Vanishes, but his recent output has been banal and sentimental; I don’t know the work of Allison Murray (the film sounds like a postcard of Buenos Aires made by a Canadian) nor Graeme Garrateguy. On the other hand, Nicolas Prividera’s Fatherland might be an interesting choice: he’s a politically engaged filmmaker, with a deep interest in contemporary Argentinean history. His first film, 2007’s M (no relation), was a very personal quest, the search for his mother, a desaparecida by the dictatorship in the ‘70s. I did see Vaquero by Juan Minujín, and found it a mess: an actor’s narcissistic try at making a film about a double of himself and showbiz, but with no care for the task of directing nor for the art of cinema itself. It shows nothing of Buenos Aires, except for the fact that there are some really bad movies made there. On the contrary, Rodrigo Moreno’s A Mysterious World is an honourable film and respectful as can be with regards to the craft—and also melancholic, as the tango tradition requires—while Las piedras, the debut film by Román Cárdenas, is very much a first feature that looks very neat and a little too stylized.

Santiago Mitre’s The Student was the sensation of the last BAFICI and comes to Toronto after winning a jury prize in Locarno’s Filmmakers of the Present competition. Made outside the INCAA umbrella, it shows the influence of two of its co-producers, Trapero and Mariano Llinás (a key figure in Buenos Aires culture, whose films are close to literature and far away from state support). Actually, the plot slightly resembles Trapero’s El bonaerense (2002) and the displaced voiceover device comes directly from Llinás’ remarkable Historias extraordinarias (2008). The Student is an extremely well-crafted movie, with great performances by Esteban Lamothe and the rest of the cast, that takes the classical subject of the newcomer entering a mafia-like organization and brings it into college politics, a significant issue for Buenos Aires middle-class youth. The Student is not only carefully written—Mitre co-wrote Leonera (2008) and Carancho with Trapero—but remarkably well-researched. Even if current explicit political references are omitted, it’s easy to recognize the true contradiction and nuances of the Argentinean political world. Not yet released in Argentina, The Student seems the kind of film where people recognize themselves, and will be especially enjoyed and treasured in the future by politicians the way mafiosi are enamoured of Scarface (1983) or The Godfather (1972).

The last Argentine film that bears mentioning is not in the City to City program, but in TIFF’s Discovery section: the winner of the Golden Leopard in Locarno, Abrir puertas y ventanas (the literal translation would be Open Doors and Windows, which sounds as meaningless as the original, but is still better than the English title Back to Stay, taken from Bridget St. John’s version of John Martyn’s love song, that plays over one scene). In principle, the film may not be considered as a “Buenos Aires movie,” because its sole location is a house and the camera doesn’t follow the characters when they leave. But since they invented the talkies, a film is not only located by its images but by its sounds as well. And in that sense Milagros Mumenthaler’s long-awaited first feature is 100% porteño: all the dialogue is spoken in the unmistakable Spanish of the Buenos Aires upper-middle-class (which is the dialect most often heard in indie Argentinean films), let’s say a couple of millimetres higher in pitch and social tone from that in The Student.

Back to Stay is a very strong film, actually something brand new in Latin American cinema, the result of a very personal and unique approach to its subject. Three sisters in their early 20s share a house. They’re orphans—it is revealed eventually that their parents were killed in an accident—and until recently they used to live with their grandmother, who died just prior to the events in the film. Left alone with their dreams, confusion, and sexual desire, they clash with each other in an endless loop of love, hate, tenderness, despair, and suffocation that gets even more heated when men are around. This is a woman’s film that redefines the idea of a woman’s film, especially because Mumenthaler is less interested in the plot than in showing bare-boned feelings, trying to make cinema go deep inside the characters and avoid all clichés. She is helped by great actresses, especially the astonishing María Canale (also a winner in Locarno) in the role of the eldest sister. Back to Stay simply proves that the lives of people remain a territory to be explored, that representation in cinema has not yet reached the limits of its possibilities, and that any true movie is somehow also a documentary.

The Boy Who Was a King (Andrey Paounov, Bulgaria/Germany)—Real to Reel

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

The boy in question is Simeon Saxe-Cobourg-Gotha, a child-monarch whose reign was severely truncated but who went on to prove that there are in fact second acts in Bulgarian lives, provided of course that you go into exile relatively rich and well-connected. A conventional documentary tracing the man’s twin stints as his homeland’s national treasure—first as a six-year old tsar and then as a democratically elected prime minister more than fifty years later—would have probably sufficed as a conversation piece; even if TIFF’s programme note is obnoxious in the way it reduces Bulgaria to punchline status, the fact is that Gotha’s story will be unfamiliar to many Western viewers despite its seismic impact at home.

But Andrey Paounov isn’t trying to make a conventional documentary, and his ambition more or less pays off. Charming, informative and formally diverse (this is one of the only non-fiction films I’ve ever seen with an expressionistic dream sequence sandwiched in the middle), The Boy Who Was a King eschews straight chronology while maintaining a credible historical perspective. Paounov understands he’s dealing with a unique figure who bridges different modes of 20th-century European leadership, but he also keeps his sights on the periphery, returning time and again to the lives of average citizens to flesh out the context of their hero worship. We meet a few Bulgarians who are old enough to remember Gotha’s coronation, as well as some similarly ancient Communists (who meet with pictures of Stalin taped to the walls) trying to follow in their political ancestor’s footsteps by running their nemesis out of the country on a rail for a second time.

Paounov also talks to taxidermists (whose duties include maintaining the royal stuffed coyote) and a Japanese-Bulgarian couple who have composed an original musical ode to their leader. Some may find the way the director emphasizes his interviewees’ eccentricities objectionable. (The whimsical music exacerbates these concerns.) Yet there’s no sense that these people have been hectored into performing or are being hung out to dry Errol Morris-style: if anything, their vividly specific behaviours transcend Bulgarian stereotypes (and insulting program notes) and help to nudge what might have been a mere profile into a more rewarding national panorama. Bonus points for the terrific orange cat who serves as a tour guide of Gotha’s home during the final sequence; not only does this scene pay off the film’s fascination with animals (frogs, fishes, and that stuffed coyote), but it’s also just really adorable.

Duch: Master of the Forges of Hell (Rithy Panh, France/Cambodia)—Real to Reel

By Kong Rithdee

By Kong Rithdee

Rithy Panh took eight years to follow up S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine with this dramatically titled documentary on Kaing Guek Eav, better known as Duch, the infamous warden of the Tuol Sleng prison. During the Khmer Rouge reign in the mid-1970s, Duch supervised the torture and killings of 15,000 “enemies”—basically every Cambodian who simply didn’t see eye to eye with the regime. Going on record here, Duch, who’s now 68 and has already been convicted for those deaths by a UN tribunal, is given a chance to reflect on his crimes, which he does openly, articulately, apologetically, and yet somehow defiantly. Duch talks at length, at times slipping in long passages from Marx, knowing that this is the only chance to tell his side of the story. What is on every viewer’s moral radar is whether Duch will say he’s sorry for what he did. And when he does say it, we see an intellectual who was nurtured and poisoned by the ideology he can never shake off even though the tremor of history has caught up with him. Panh recycles a lot of footage from S21, plus archival film from the Khmer Rouge era. But it’s Duch who holds court here, definitely for the last time.

Hard Core Logo II (Bruce McDonald, Canada)—Masters

By John Semley

By John Semley

Granted, the title is a cheat. Hard Core Logo II is not only not about the seminal fake Canadian punk band Hard Core Logo, it’s also not about the not-at-all seminal real Canadian pop-punk band Die Mannequin, whose front-pouter, Care Failure, is the film’s ostensible subject. Hard Core Logo II is about Bruce McDonald, both the in-quotes character in the film—who, following the success of his controversial documentary Hard Core Logo, has defected to LA and is living in a Canadian filmmaker’s Shangri-La, securing steady TV work—and the actual guy behind the camera.

“Bruce McDonald” heads to blowy, unfeeling Saskatchewan to document Failure, who claims to be channelling the spirit of Joe Dick, Hugh Dillon’s suicidal punk rocker from the first film. Soon all of Failure’s sub-Courtney Love snarling recedes, along with all the industry in-jokes and the laboured meta-wrinkles, as McDonald enters the frame more fully. If he was fogeyish and out-of-touch as recently as last year’s This Movie is Broken, McDonald seems to have come to terms with his shifted status from Can-cine punk rock pioneer to slumped elder statesman. Hard Core Logo II gets fairly warts-and-all, showing McDonald getting too stoned, slobbering lecherously over Failure and, sin of sins, missing his wife and kids while on the road. All the magik (“that’s magik with a ‘k’,” the film clarifies) and lite-Satanism the then-young filmmaker dabbled with back in the days of Highway 61 is considered here with a refreshing, knowingly geezerish distance. Stylishly shot and spiritedly edited in a way that deliberately recalls McDonald’s earliest features, Hard Core Logo II realizes the promise that most of us had forgotten about. It’s also got the best joke about the penalties of signing “November Rain” at karaoke that’s likely to have ever appeared on film. Though I haven’t exactly fact-checked it.

Hors Satan (Bruno Dumont, France)—Masters

By Andréa Picard

By Andréa Picard

Much closer to Bruno Dumont’s earlier films like La vie de Jésus (1997, winner of both the Camera d’Or and Jean Vigo prizes) and L’humanité (1999, Cannes Grand Prix winner) than to the more accessible and conventionally likeable Hadewijch (2009)—a film that brought him a host of new admirers despite its dubious treatment of terrorism—Hors Satan is set on the Côte d’Opale along the Atlantic Coast of northwestern France in the Pas-de-Calais, not far from where French officials recently cruelly cracked down on young migrants hoping to make it to the UK. The gorgeous and expansive dune-filled landscape magnificently stretches across the CinemaScope frame (superbly rendered by Yves Cape with focus-pulling perfection), providing Dumont with his most painterly setting yet, all sinewy and seeped in rich, dew-drenched earth tones. The film is a sight to behold with an elemental formal vocabulary mainly comprised of wide establishing shots (a strata of horizontal landscapes) and close-ups (faces and hands) that conspire in an entrancing monumental minimalism bathed in the sort of mystical crepuscular and early-morning light famously featured in Dutch genre painting. It’s his most formally precise film, his most Bressonian, and a helluva challenge to champion.

Scored to raw mono recordings of breath and wind recorded live, diegetically on set, Hors Satan (which sports the awkward English translation of Outside Satan) was strangely derided for being too openly interpretive (the WTF syndrome) with its disciplined (quasi-structural) de-dramatization and its nameless characters. He (David Dewaele, who played minor roles in Flandres and Hadewijch) is a rugged, impish hunter with glinting grace in his long-lashed blue eyes and She (non-actor newcomer Alexandra Lematre, who Dumont found in a local café) a skinny, spiky-haired goth girl with a translucent pallour and trembling fragility. She lusts for him, and while he consistently rebuffs her clumsy advances, he becomes her protector from the men who surround and torment her. But he’s both a guardian angel and an exterminating angel, one who kills in between meditative prayer sessions. The rugged hands of a supplicating hunter (of man and animal) are cleansed then cupped upward in an expression of faraway spiritual repose. There are incidents of brute carnality and violence, of course, and an impossibly spectacular conflagration appears out of nowhere, a Hades on earth—awesome and terrifying, and made suddenly to disappear. But as a whole, the film evinces an unusually languid and contemplative tone, wrapping the film’s intrinsic enigma in a discomfiting naturalism. What Dumont has referred to as the “incivility” of the film, its possibility of a Jesus-Satan figure (one who can presumably walk on water but forces others to instead) suggests the ultimate metaphysical battle with a subversive sense of deliverance. Bernanos and Bergson are guiding forces (maybe Zola, too), with Pialat’s controversial Palme d’Or winner Sous le soleil de satan (1987) lingering not far behind. There are exorcisms and a miraculous resurrection in Hors Satan, but Depardieu’s self-flagellating priest beset by a crippling lack of faith is here replaced by a dispossessed though thoroughly self-assured figure who embodies both good and evil, who can perform miracles without selling his soul to the Devil, as that would, simply speaking, be redundant.

Hors Satan’s elliptical nature and multiple readings are firmly beholden to the film’s form; Dumont has referred to his emphasis on “sensations” and the retrospective (instead of fleeting) meaning of images attained through careful composition and construction. With a striking refinement and reduction of his palette, and a sly sense of humour (yes, Buñuel should be added to that “B” list of influences), Dumont has reached a new level in his filmmaking. The absurd attacks launched at the film truly exist elsewhere (everywhere?) in varying degrees. Dumont’s new film makes a strong case for art transcending dialectical logic, using the cruel contradictions that encircle us in order to reflect them back. They may be ghastly, morally reprehensible, and perversely awash in beauty. And in the case of Hors Satan, they are also intrinsically tied to its specific Northern French landscape. Franju would undoubtedly concur.

The Last Christeros (Matias Meyer, Mexico/The Netherlands)—Visions

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

In his third film, Matias Meyer still hasn’t found what he’s looking for. But his characters are getting closer. The French-born, Mexico-schooled filmmaker has a thing for wanderers: his genuinely experimental 2008 debut Wadley concerned a peyote-tinged vision quest, and 2009’s The Cramp (which I have not seen) has been described as very much a figures-in-the-landscape affair. With The Last Christeros, Meyer takes his fondness for sprawling desert vistas and puts it in the service of a historically significant story: the guerilla battles waged by devout Mexican rebels against the country’s government and armed forces.

Meyer would probably—or hopefully—be the first one to admit the influences of Albert Serra and Lisandro Alonso on his distanced, long-take aesthetic, although The Last Christeros is comparatively action-packed. There are gunfights and narrow escapes, although they’re so attenuated that the story seems to be happening in slow motion—the conscious and not always successful choice of a young director committed to certain fashionable notions about contemporary filmmaking. Which is not to say that The Last Christeros is prefab slow cinema. Meyer may have been drawn to the subject of the Christeros War for its visual possibilities (bearded men on horses framed against the mountains), but he’s also invested in his revolutionaries’ spiritual outlook and the doubts that creep in during their peregrinations. “I must confess to you in all this time I never felt so lonely,” says one during a nighttime vigil, adding “I think we should quit the revolution.” Their doggedness is admirable, and so, by the end, is Meyer’s: after searching for 90 minutes for an authentic grace note, darned if he doesn’t find it.

Lipstikka (Jonathan Sagall, Israel/UK)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Diego Lerer

By Diego Lerer

Two Palestinian friends who share a traumatic incident from their teenage days in Ramallah are reunited in present day London, where their relationship is put to the test as director Jonathan Sagall starts to reveal, via a series of flashbacks, the problematic and complicated relationship they have had over the years. Poorly acted and directed, with risible dialogue and a script that piles on a huge amount of incidents (drinking problems, drugs, cheating, threesomes, political troubles, rape, torture, etc.) as if it were ten TV movies in one, Lipstikka is one of those movies that belongs solely to film festivals for all the wrong reasons.

A Mysterious World (Rodrigo Moreno, Argentina/Germany)—City to City: Buenos Aires

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

Less mysterious than vapid, Rodrigo Moreno’s follow-up to his interesting first film El custodio spins its wheels until it arrives at a dead end. Those wheels belong to an aging Romanian auto that sad sack Boris (Esteban Bigliardi, who looks lost and uninspired) tries to drive around while figuring out what to do with his life now that his girlfriend has apparently dumped him. Boris’ biggest decision in a film of microscopic changes and stasis is to have the lousy, Trabant-type car given the once-over in an auto repair shop, where the film momentarily comes to life before slumping back into its generally sleepy state. Moreno’s idea behind this project is utterly opaque; where El custodio trucked in a studied form of minimalism that was in concert with its view of a suffocating political atmosphere at the highest level of government, A Mysterious World is about nothing more than a dude who can’t get his shit together, and it’s arguable that it’s even about that. No, on second though, it’s really about nothing.

Nuit #1 (Anne Émond, Canada)—Canada First!

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

Nuit #1 marks feature number one for Anne Émond, who, on the strength of her shorts Naissances and Sophie Lavoie, is a good filmmaker: both films are intelligent, visually and narratively precise examinations of young women dealing with the fallout from their sex lives. Nuit # 1 is technically a two-hander between both halves of a post-rave hookup—He (Dimitri Storoge) a caustic, chronically underachieving recluse, She (Catherine Lean) a self-possessed yet tremulously sensitive grade-school teacher—but by the end, it’s clear that Émond is more invested in the feelings and frailties of her distaff mouthpiece.

And truly, that’s all that Lean’s character is: a mouthpiece for a writer-director who has a lot to say about the ins and outs of modern love and crams as much of it as possible into 91 minutes. Or, more accurately, into about 70 minutes, since the first movement of Nuit #1 is basically dialogue-free, given over entirely to real-time (though probably not real-live) images of our protagonists rutting like jack-rabbits. Their passions spent, they then talk (and talk, and talk) about their one-night stand and then their respective lives, each inevitably hitting upon the other’s deepest fears and neuroses. The switch from harmonious non-verbal interaction to stripped-down emotionality and pumped-up chatter is theoretically striking, like a Claire Denis movie bleeding into one by Catherine Breillat. But the transition is too abrupt, and the actors too weirdly poised, for us to really believe what we’re seeing. Émond aims for a heightened, intimate realism, yet the thematic undergirding keeps rudely poking up from underneath the skin of the film. Émond ‘s big mistake is to try, along with her characters, to inflate this one-night stand into something revealing and profound—a po-faced piece of generational portraiture.

The Other Side of Sleep (Rebecca Daly, Ireland/Hungary/The Netherlands)—Discovery

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

Subjectivity is a dangerous game for filmmakers to play, but oh so tempting. Inherently cinematic (which does not ipso facto make it desirable or even good), the strategy restricts the viewer’s perspective and at its best investigates the sensation and politics of voyeurism and the optics of mortality, a simulation of the point of view of a human being rather than the godlike high angle or long shot. It can compound a film’s meaning, or it can be nothing more than a gambit, which it often feels like in writer-director Rebecca Daly’s account of a young woman afflicted with sleepwalking and pressured by the fear of a killer on the loose. Daly’s own comments concentrate on what she views as the media’s bloodlusting irresponsibility while pursuing headlines during sensational murder cases like the one depicted here. But that isn’t the film she’s made; rather, her interest is in keeping the viewer unhinged by seeing things through the prism of a sleepwalker’s semi-psychotic insomnia, which harbours within it the possibility that she might unknowingly be the killer herself. This ends up being a fairly cheap trick to encourage involvement, which regularly wanes during a scenario replete with all manner of ridiculous activity (to wit, the woman’s habit of walking alone late at night down lonely stretches of rural Irish road in the midst of a murder spree). When the M. Night Shyamalanish twist finally happens, it fades quickly, much like Daly’s film.

Restless (Gus Van Sant, US)—Masters

By Kiva Reardon

By Kiva Reardon

Those looking for a definition of “twee” need look no further than Gus Van Sant’s latest. Enoch (Henry Hopper) is an odd teen who dresses like Edgar Allen Poe and talks to a ghost of a Japanese kamikaze pilot (Ryo Kase); Annabel (Mia Wasikowska) is a bubbly young girl who memorizes the Latin names of sea birds and has a wide and varied collection of brooches. Both have a fascination with death, as Enoch lost his parents in a car crash and Annabel, we soon discover, is dying of cancer.

If one is feeling generous—and why not? —it’s possible to see Restless as a relatively competent, albeit highly melodramatic, portrayal of how our lives are touched by a fascination with death. On the other hand, if one is feeling less inclined to make thematic justifications for its precious content, what we have here is just a very morbid manic-pixie- dream-girl film, where an unconventional short-haired saint must die in order to leave her male friend with a richer view of the world (all while listening to Iron and Wine). I think the viewer’s decision hinges on the scene in which Annabel and Enoch stage her death: shot as if it were part of the “real” movie, Annabel suddenly breaks character to pause the music and chastise Enoch for going off book, accusing him of “upstaging her passing” by threatening to perform seppuku (that’s what happens when you hang around with dead Japanese people, apparently).

Perhaps this bit of cinema interruptus can be taken as a meta-joke, but the problem with the gambit is that in trying to draw our attention to how movies (and the broader culture) romanticize death, it doesn’t spike the monotonous tweeness of the film nearly enough. Van Sant has crafted a nice dual career experimenting with arthouse forms and exploiting mainstream ones, but this new film strikes a mediocre and pointless middle ground. While the opening superficially recalls My Own Private Idaho—a young male protagonist on a road waiting for his journey to begin—Restless takes neither its characters nor the audience down an interesting path (and Keanu Reeves is sadly nowhere to be found). This inveterately restless director had made a movie that makes the audience feel the same way—as in waiting for the credits to roll so that they might exit the theatre.

The Sword Identity (Xu Haofeng, China)—Discovery

By Shelly Kraicer

By Shelly Kraicer

Xu Haofeng’s debut feature is a mysterious wuxia film that is both an homage to and an elegant, comic deconstruction of the classic Chinese and Japanese martial arts cinema traditions. The typically convoluted plot takes place in a southern Ming dynasty setting, where Liang Henlu (Song Yang) and a colleague, sneaking into town, are mistaken for Japanese pirates by government soldiers. Handsome, dashing Liang is in fact a disciple of anti-Japanese fighters, who had used specially modified Japanese long swords to defeat said pirates. Seeking to establish his sword technique as a recognized martial art, Liang stages a series of combats with the town’s official martial arts sects, involving a comic chorus of Xinjiang maidens, the estranged wife of a great master swordsman (along with her young, not-so-secret lover), and a bumbling quintet of hapless soldiers. The final master vs. swordsman showdown is refined to a pure philosophy of swordplay, where age faces youth and non-action vies with action. Paying tribute to King Hu’s aesthetic of ultra-fast, barely glimpsed action, Xu succeeds in injecting a fresh combination of both idealism and realism into the classic wuxia visual language. With brilliant sound design and strong inventive cinematography, this is an utterly up-to-date classic, a comic-epic swordplay film for a postmodern age.

We Need to Talk About Kevin (Lynne Ramsay, UK)—Special Presentations

By Andrew Tracy

By Andrew Tracy

On the slim basis of three features (plus the tellingly titled short Small Deaths), inexplicable death seems to be Lynne Ramsay’s chief subject, whether via accident (Ratcatcher), suicide (Morvern Callar), or murder in The Lovely Bones (a film she was attached to for a considerable amount of time) and her new film We Need to Talk About Kevin. While Ramsay dodged the bullet on Bones by ceding that no-win prospect to Peter Jackson, she walks right into another one (or rather an arrow) with Kevin, which will surely rank as one of the more embarrassing films by a talented director to screen this year. As many a wag has already noted, this adaptation of a bestseller of dubious literary value is essentially Elephant crossed with The Omen, as demon child Kevin (Jasper Newell as the scowling moppet version, Ezra Miller as the lean-hipped teen dreamboat) torments his bewildered mama (Tilda Swinton) from infancy and finally caps it off with a Columbine-style school massacre just prior to his 16th birthday.

The opening shots are already enough to make the spirits droop: a softly/ominously blowing curtain cuts suddenly to an overhead shot of hundreds of writhing merrymakers bathed in tomato-juiced crimson at Spain’s La Tomatina festival, a thuddingly obvious prelude to rampages to come. If one can thus already tell that Ramsay has foregone the virtues of subtlety, the first ten minutes at least holds out the hope that she might direct this ridiculous material with her usual deftness, as she shifts back and forth between time frames with a series of adroitly executed visual and aural rhymes. Alas, when we cut from Swinton screaming in childbirth (her face monstrously distorted through the glass of a medical apparatus) to baby Damien (whoops) squalling to high hell, it’s clear that these patterns will lead precisely nowhere, certainly not into the marvellous, eerily implicative textures of Ratcatcher or Morvern. As Tilda and tot (with clueless pa John C. Reilly occasionally floating into view like a Brillo-haired blimp) face off over the years, Ramsay deploys a hodgepodged barrage of art-film devices—her own familiar woozy immersion, Antonioni-Jarmuschian decentred framings, Hanekian sterility, etc.—that only accentuates the worthlessness of her irredeemable material. If Kevin is nothing more than an empty shell of motiveless malice from the get-go, there is nothing of any dramatic substance to be gained from the lugubrious exposition of his evil, which makes Ramsay’s po-faced playing-straight all the more risible. A Polanski might have seen the innate silliness of all this and served up a devilishly clever spoof, but the fact that all this horror-show mummery connects itself to—and pretends to tell us something about—the wellsprings of real-life horror is so tasteless that any humour, whether intentional or inadvertent, withers right away.

cscope2