TIFF 2020: The Inheritance (Ephraim Asili, US)

By James Lattimer

Published in Cinema Scope #84 (Fall 2020)

The role of past insights in (still) present-day struggles is at the heart of The Inheritance, a playful, erudite, and boundary-blurring examination of what performing Black theory, literature, music, and testimony in a contemporary Philadelphia commune might set in motion. Given even greater topicality by the current moment, Ephraim Asili’s first feature has no problems transcending it, not least in its insistence on continuity and process. Too smart to trade in conventional activism and too wry and funky to feel overly academic, Asili’s unique project is ultimately about intertwining theory and practice and making sure both are passed on to the next generation, an idea that reverberates far beyond the walls of the house.

The founding of the commune that forms the film’s central setting hinges on a literal inheritance, in the form of the West Philadelphia home that Julian (Eric Lockley) has been left by his grandmother. After he asks his on-off girlfriend Gwen (Nozipho Mclean) to move in, a chain reaction ensues, and soon they are sharing the house with an entire collective: Patricia (Nyabel Lual), Stephanie (Aniya Picou), Mike (Michael A. Lake), and Janet (Aurielle Akerele), musicians Old Head (Julian Rozzell Jr.) and Jamel (Timothy Trumpet Jr.), and, lastly, Julian’s old friend Rich (Chris Jarell). It’s Old Head who first articulates the commune’s goals together with its name: the House of Ubutu, a place focused on and geared towards the preservation and self-care of Black people.

Little information is provided on the collective’s respective backgrounds and interests, which emerge instead by way of their interactions and involvement in house activities. These are frequently informed by what was also left behind by Julian’s grandmother: an almost bottomless collection of books, records, magazines, newspapers, photographs, posters, and other materials so casually far-reaching and eclectic that they just so happen to make for a perfect syllabus for learning about the wider Black experience, taking in key works of African-American literature, politics, and theory while also finding space for other authors and academics examining the African experience as well as other political struggles or post-colonial settings.

Gwen and Julian thus pace through the house delivering sections from Julius K. Nyerere’s Essays on Socialism, Patricia gives the group a workshop on the Nuer language of South Sudan after dancing to Old Head and Jamel’s jazz-inflected jam session, while Janet leafs through volumes of Sonia Sanchez’s poetry. While these activities take their bearings from myriad different sources, they share a similar goal at a superordinate level: embodying past texts in the present to keep them alive while tapping into the fresh meanings and sensations they can still trigger.

The grandmother’s collection doesn’t just serve as a jumping-off point for the house’s activities, though, but also comes to adorn its walls, as if to imply that keeping such references visible in everyday life is a fundamental component of the educational and political processes being explored by the commune, if not more generally. When these visual materials are shot front on in close-up against the strongly saturated hues in which the walls are painted, the resultant flattening effect makes them appear more like a theatre set or even part of an art exhibition than some actual lived-in abode. A similar effect is created when the residents themselves are shot front on before the same walls, adding an extra layer of artifice to their actions, which are often already performative in the first place.

Taken together with the grandmother’s immaculately curated collection, this all gives the impression that The Inheritance is more about crafting an overtly constructed space for political exploration than creating a portrait of a real-life commune. The fact that a poster of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) has been placed in prominent position in the kitchen is thus no accident. Furthermore, both films make the walls of their respective settings home to pertinent quotes, written in this case in chalk on a black background between the striking colours and the other wall decorations.

For all this artifice, however, this apparently fictional set-up is actually a “speculative re-enactment” based on Asili’s own experiences in a Black Marxist collective in West Philadelphia. But this is by no means that only way in which life outside the commune’s colourful walls enters The Inheritance. From the outset, Asili intersperses the collective’s exploits with images of the West Philadelphia cityscape and sporadic interviews with the actors playing its members shot in monochrome, both of which interact with these exploits despite being formally distinct from them. The various murals in the city behave much like the house’s walls in terms of keeping the political in plain sight, while the content of the actors’ interviews barely differs from the content they explore in their roles, with the same focus on explicating theories, ideas, and the thought processes they provoke. Old Head may introduce the House of Ubutu in character and in colour, but it’s easy to imagine him saying much the same thing as Julian Rozzell Jr., particularly as the form of address is identical.

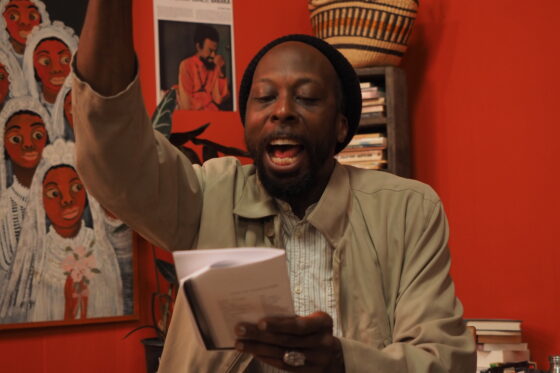

These insertions already establish the boundaries between inside and out and actor and role as porous; other elements from beyond the four walls of the house also enter them to up the ante further. Archive footage also appears from time to time, such as when a pan down onto Gwen’s “Chisholm for President” sweatshirt segues into a video of the 1972 presidential candidate giving a rousing speech, or when a commemorative plaque about the 1985 MOVE bombing ushers in a montage of historical TV reports and written documents on the West Philadelphia action group; over the next scenes, three of their surviving members even come to the House of Ubutu themselves to recall their astounding, harrowing experiences. Two other local figures also make an appearance: Sonya Sanchez recites one of her poems, while celebrated spoken-word artist Ursula Rucker gives a performance at the house that more or less rounds off the film. Aside from injecting the urgency of action actually experienced into the fictionalized setting, incorporating these various real-life figures into the film also infuses all the theory on display with a necessary portion of practice, both past and present. As the Kwame Nkrumah quote that appears on the wall at one point states, “Practice without thought is blind; thought without practice is empty.”

The fact that Sanchez delivers her poem at her own home is due to an (offscreen) incident in which Rich refers to her as a bitch, much to Gwen’s chagrin. The tensions between Rich, who seemingly comes from a less academically minded background and knows Julian from a very different context, and the rest of the commune, form a running gag of sorts, whether through his unwillingness to abide by the house’s no-shoes rule or his cluelessness as to the use of spirulina. Humour also emerges in other conversations too, such as when Stefanie tells Gwen about her experience of being picked up at a café by a white woman who is dismayed when Stefanie doesn’t like the Black film they watch on their date. In addition to cannily leavening the film’s considerable quantities of politics and theory, these wry quotidian moments ultimately also feed into the same idea of how theory cannot exist in isolation from practice. A political commune can only function if its members are able to navigate living together too; any revolution is rooted in the everyday.

Once the film’s closing performance comes to an end, thoughts turn quite literally to the future generation in the form of an unplanned pregnancy, which also neatly serves to extend the line connecting the different temporalities that flow through The Inheritance. Starting from the generation of the grandmother, whose thoughts were already informed by texts stemming from further back, passing through the endeavours of the MOVE group and their contemporaries to reach the efforts of the commune, themselves a recreation of a time now already in the past: what are political ideas, theories, images, articulations, and slogans there for if not to be passed on and thus progressively transformed, also into cinema? The next generation’s inheritance is already here.

James Lattimer