TIFF 2015 | It All Started at the End (Luis Ospina, Colombia)—TIFF Docs

By Steve Macfarlane

Long before “poverty porn” was popular parlance, a tight-knit network of filmmakers and artists in Colombia made Agarrando Pueblo (The Vampires of Poverty), a satiric mockumentary about Latin American documentarians “selling images of poverty to Europe” to boost their own careers. The 28-minute short gets a few minutes’ special attention in Luis Ospina’s wild and woolly memoir-documentary It All Started at the End, but it’s just a drop in the bucket of works made by Ospina, his late colleague Carlos Mayolo, and their Grupo de Cali (named for the town in Colombia where they all first met). The “end” in the title refers to Ospina’s own diagnosis with a metastatic GIST, prompting a long-in-hindsight evaluation of an obsessive’s life spent making movies and finagling collectivist activism. That said: as the first 45 minutes of the film follow Ospina into the hospital for treatment, the filmmaker turning the camera on himself, his nurses, his meals, his girlfriend, and even his own innards, one couldn’t be blamed for wondering whether one has walked into the wrong movie.

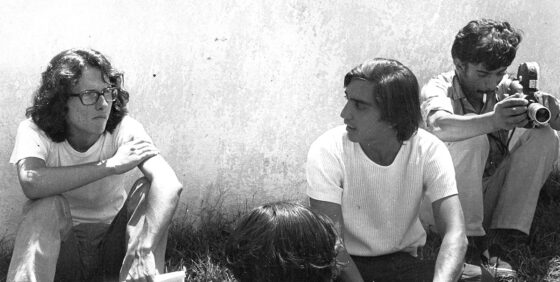

It’s only when Ospina convenes a dinner party with remaining Grupo members that the recollections start flowing like wine, and their memories begin to stitch into the narrative, alongside home movies from decades prior, cameos in Cali Group works, and an overabundance of candid stills. The Group began with the Ciudad Solar, a communitarian movie theatre/bookstore/production office/art gallery founded in mid-’70s Cali by Ospina, Mayolo, and the author/poet/critic Andrés Caicedo. The question of Caicedo—who committed suicide in 1977, at the age of 26—is introduced in a clip from an in-memoriam documentary Ospina made in the ’80s, wherein a woman with a microphone asks passersby on the street “Who was Andrés Caicedo?” One young man offers that he was “a nadaista,” to giggling and consternation. (Here’s Caicedo the teenage film critic, on Jerry Lewis: “We believe ourselves to be far less perfect than we are, and this is what drives us to break a vase in the middle of a visit.”)

One of the partygoers, a Cali Group screenwriter who tells the camera he’s just taken his first drink in five years, offers this: “Were we a movement? A generation? I’m not so sure. Generations were invented by books, by cinema, by death…” Over the film’s three and a half hours, Ospina wastes little time contextualizing the Group’s politics for unaware or non-Colombian audiences, preferring instead to keep things rooted in first-person discussion. Colombia’s sordid history of drug trafficking, police crackdowns, and decades-long civil war with the FARC is rendered in a single time-lapse compilation of news footage, scored to a punk song that both explains the hard-living Grupo’s pervasive nihilism and indicts it: everything’s fucked, so we might as well make movies and have a party while it burns. As one of Mayolo’s exes explains, “We celebrated the start of shooting, because we were shooting, or because we’d just finished shooting.”

While a number of Ospina’s filmmaking decisions are kooky as all get out, highbrow formal considerations take a backseat to the urgency, the personality, and the sheer richness of the filmmaker’s excavations. Ospina shows himself not just explaining the project to his interviewees, but arguing about it; he frames them against their younger selves à la the Up series, extending an arm from behind the camera to hold the hand of Mayolo’s partner as she remembers their life together. At the Q&A following the film’s world premiere at Toronto, Ospina advocated a kind of “critical nostalgia”: “I’d like to quote Jean Cocteau,” he said. “Mirrors work to show us death. For me, the camera is the same thing. In my opinion death is the absence of memory, and letting themselves be filmed is one of the most generous things a person can do.”

At one point in the film, Ospina runs a complete list of Grupo productions down the screen; only a fraction of the titles included are even listed on IMDb. For myself, having shuffled into the screening knowing nothing about Colombian cinema—the Cali Group’s greatest claim to fame is probably assisting Werner Herzog in the shooting of Cobra Verde, which allows one of Mayolo’s ADs to call Klaus Kinski “a real sonofabitch with eyes in the back of his head”—I was reminded, not for the first time at Toronto, of a plain but uncomfortable fact: the canon is not a meritocracy.

Steve Macfarlane