TIFF 2013: Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Mohammad Rasoulof, Iran)—Contemporary World Cinema

From Cinema Scope #55, Summer 2013

By Richard Porton

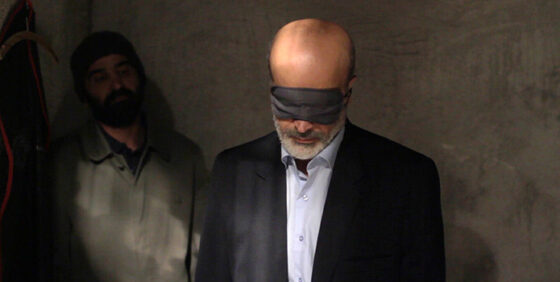

By contrast to The Past, this year’s predominant Iranian Cannes entry, Mohammad Rasoulof’s Manuscripts Don’t Burn (which screened in Un Certain Regard and took home the FIPRESCI prize for that section), is not at all evasive when it comes to politics. Filmed clandestinely in Iran with a cast that must remain anonymous to protect their own safety, Manuscripts bypasses allegory entirely and levels a lightly fictionalized j’accuse against the abuses of Iran’s autocratic state in the age of Ahmadinejad. The film’s title is an allusion to a famous passage in Soviet writer Mikhail Bulgakov’s anti-Stalinist novel The Master and Margarita, and Rasoulof obviously encourages the viewer to draw parallels between the Iranian regime’s repression of dissident writers and Stalin’s disdain for literature that challenged socialist-realist shibboleths.

Whether due to a deliberate strategy or the technical constraints imposed by shooting sub rosa, there are elliptical aspects of Rasoulof’s narrative that make mincemeat of Jonathan Romney’s attempt in Screen Daily to label it a Costa Gavras-style thriller. The contrapuntal structure yields two narrative strands that converge by the film’s conclusion. In the film’s opening sequences, Rasoulof adapts the intriguingly perverse ruse of viewing state terror from the perspective of the victimizers instead of the victims: two government agents drive around town engaged in what would seem like banal domestic banter, until we realize that they are motoring with a man they’ve bound, gagged, and thrown in the trunk. Although this is not as extreme an exercise in getting inside an unsavoury point of view as, say, Jim Thompson’s novel The Killer Inside Me, the skewed narrative vantage point is destabilizing enough to induce queasiness. The other narrative strand involves rather arid bickering between elderly, disillusioned writers on the state of intellectual debate in the age of the internet, which culminates in a shockingly matter-of-fact murder of one of the dissidents. These strands finally coalesce in a colloquy towards the end of the film between the thugs’ elusive quarry Kasra—a writer whose manuscript chronicling the bungled murder of rebellious writers during the so-called Chain Murders of the late 1980s and 1990s—and a journalist and former dissident who now carries out the dictates of the state.

Unlike most thrillers, political or otherwise, there isn’t a satisfyingly cathartic conclusion to Manuscripts Don’t Burn, only a thwarted dialogue in which the representative of the status quo claims that rebellious intellectuals have joined some ill-defined entity known as “the cultural NATO” and is met by Kasra’s defiance. Still, the unresolved nature of their interchange is infinitely more satisfying than The Past’s overheated bag of melodramatic tricks.

Richard Porton