The Reckless Moment: 5 MDFF Shorts at The Royal

By Adam Nayman

The mission statement of the Toronto-based production company Medium Density Fibreboard Films expresses a desire to focus on “projects that display a strong sense of cinematic handwriting.” So if I say that the films of Kazik (Kaz) Radwanski feel as if they’ve been jotted down, I mean it as a compliment. Instead of playing like audition pieces for future features, the micro-budgeted and superbly realized short films he’s developed in collaboration with his producer, fellow Ryerson grad and MDFF co-founder Daniel Montgomery, give the impression of unfolding in the moment: you could say that immediacy is his artistic signature.

Watching Princess Margaret Blvd. back in 2008, where it stuck out in the Short Cuts Canada Programme I was reviewing for what used to be Eye Weekly, I had the feeling I was in the hands of a real filmmaker from the quietly arresting opening sequence, where the camera trails a woman down a residential street in between precisely timed cuts. The simultaneous sensations of focus and disorientation are key to a movie about a person coping with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis—a potentially mawkish subject treated without sentimentality or the urge to universalize the character’s experience. In lieu of any statements about living with disease, Princess Margaret Blvd. resonates as a patient, specific bit of portraiture.

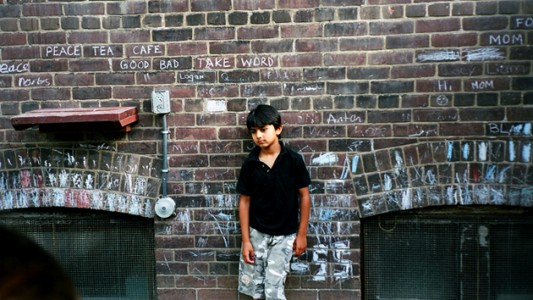

There’s a sense in which all of Radwanski’s films are about individuals set against systems or problems beyond their immediate understanding. Assault (2007) opens with its 19-year-old protagonist cold-calling lawyers to get advice about an impending assault charge: each new conversation reveals more about the incident while keeping the action rooted in the present tense (and the camera rooted on his anxious young face). The surprisingly (and deservedly) Genie-nominated Out in That Deep Blue Sea (2009) follows a middle aged-real estate salesman in the throes of what may be a dry spell or a midlife crisis: his daily exertions on a living-room treadmill do nothing to alleviate his sense of personal and professional paralysis. Once again, the action is shot at close proximity, but the structure is looser and more episodic, allowing for digressions—like a dinner table argument between the main character and his teenage daughter— that have the sullen ring of truth. Green Crayons (2010), an elementary-school parable about pre-emptive loogie-hawking, finds its young characters rightly baffled by adult notions of justice and retribution; if it’s a little more schematic than its predecessors, it’s no less keenly observed.

At times, the confidence of Radwanski’s aesthetic, which obviously owes a little bit to the global influence (if not the actual films) of the Dardennes, bumps up against the amateurishness of his actors—usually in interesting ways. (The lead performance in Out in That Deep Blue Sea has a flustered, flailing quality that suits the role.) His insistence on using non-professionals and developing certain scenes collaboratively ties into MDFF’s industrious, under-the-radar ethos, but it also speaks to a genuine curiosity about filmmaking practice. This sort of open, exploratory mentality is rare in institutionally produced Canadian short films, most of which feel script-consulted to within an inch of their lives.

Radwanski and Montgomery are committed to what they call “reckless” filmmaking, outside the regular production stream and within a close-knit circle of collaborators. They’ve used the same cinematographer (Daniel Voshart), editor (Ajla Odobasic) and art director (Eva Michon) on all of their films, but they’re also interested in bringing other filmmakers into their orbit. The showcase of MDFF’s output playing at Toronto’s Royal Cinema on Wednesday, May 18th also includes the fine Vancouver-produced short Woman Waiting by Antoine Bourges, a measured character study of a woman slowly slipping through an urban social safety net that played in competition in Berlin alongside Greeen Crayons earlier this year. Radwanski and Montgomery were also invited to program a series called “First Generation” at the Lichter Filmage in Frankfurt dedicated to new Toronto filmmakers; their selections included Nicolas Pereda’s excellent Interview With the Earth (2008) and Chris Chong Chan Fui’s Pool (2010).

At a time when Toronto’s filmmaking hierarchy is hopefully undergoing renovations—Exhibit A being the happy and unlikely fact of Daniel Cockburn’s You Are Here showing at TIFF alongside more conventionally Canada First!-type productions—MDFF’s desire to reach out to other young directors is nearly as heartening as their industriousness. This filmmaking collective named for a construction company is building something.

SCOPE: Why is the company called Medium Density Fibreboard Films?

RADWANSKI: The name comes from my family’s business, which is a construction company. My grandfather worked in construction and my uncle as well, and I think the underlying instinct to form a small, close group, as well as the name, comes from that side of the family. The same way that my uncle hates dealing with building permits, I think I would hate working with acting unions, or large crews. The way my uncle works at the site is with four or five people, small crews. When Dan and I were at film school together at Ryerson, we wanted to make Assault, and we were pretty much told by everybody not to do it, that we shouldn’t make it, and that brought us together and made us more determined to do it. And so from there, when we wouldn’t get grants or when the film was finished and we didn’t get into festivals, I think it spurred us on even more.

SCOPE: Can you talk about what you both learned being part of a filmmaking program at a university? Was it as much about learning what not do to?

MONTGOMERY: One thing I noticed is that everyone [there] wants to direct. 90% of the people at Ryerson wanted to direct, because they felt like they had some sort of great vision. I wasn’t interested in producing when I started either, but I came to realize that there was a need for that sort of shaping process, as opposed to some grand delusion about how films are made. That’s how we started working together.

RADWANSKI: Film school was interesting. I don’t know what I expected it to be like, but I’ve never been a good student. When I was there, I never had a mentor, I don’t feel like I was shaped by anyone. It was a great place to meet like-minded people and figure out who I could work with and who I couldn’t. You learn from negative experiences. Dan and I got sick of a lot of the nonsense there, people being really competitive, making power moves trying to be the big production, trying to sneakily align a group of people. What we were more interested in was getting a group of people together to talk about the films we were seeing and the films we wanted to make, and figure out collectively how to go about it.

SCOPE: Were those like-minded people in short supply?

RADWANSKI: It’s not just in short supply at Ryerson, it’s in short supply in general. You can tell when you meet somebody how interested they are in cinema, what kind of a role it plays in their lives, and how they interact with it. One of the reasons we work with Antoine Bourges is that we don’t know too many other Canadian filmmakers like him.

MONTGOMERY: There’s a group of Canadian filmmakers who we do see eye to eye with. I think Nico Pereda is one of them, he’s doing some exciting things. He’s somebody we see ourselves sharing a sensibility with, like we have some of the same ideas about cinema.

SCOPE: Assault is a movie made with a lot of confidence, but I’ve heard you guys say that you sort of found the form as you went along. Can you elaborate?

RADWANSKI: A lot of the aesthetic decisions we made on Assault had to do with just how bad we thought acting was in film school. That seemed like the biggest hurdle. Cinematography, editing, sound, art direction: we could see those things naturally progressing as we went along and thought they would get better with time, but with acting, we were worried about getting performances that weren’t embarrassing. So when we started doing documentaries [in school], it was the first time I wasn’t embarrassed: when something real happened, an actual moment, it allowed me to ground the film and it helped me get over my fear of working with actors. A big turning point for me was the opening scene in Assault, where we got our lead to just open up the phone book and start calling real lawyers. I knew that that was going to be interesting, because he was really going to have go after these people on the phone and try to get something out of talking to them, some sort of offer.

SCOPE: Are you afraid that if you guys move on to bigger productions or feature films that your method of finding and working with actors is going to get altered?

RADWANSKI: I’m afraid of it, yeah. I remember reading something Lisandro Alonso said about how if he couldn’t make the films he wanted, he’d go work on a farm, something like that. I know it sounds like a silly thing to say, but the most depressed I’ve ever been was when I was working for a large production company in an office. I’m afraid of compromising. I feel like if somebody gave me a two-million-dollar budget for a movie, I’d honestly be worried about not fucking it up, about making a movie that people want to see. And if a producer started stressing out about what that movie was, I’d probably end up listening to him. I want to get stronger, so I can head-butt back against that sort of thing.

MONTGOMERY: At first, the way we were going about making these films was purely about practicality. We had no money. That dictated a lot of it. Now we look at it as a conscious choice. We’re not 22 anymore, but we’re still quite young. We don’t have families and mortgages, so we can afford to be a little bit reckless, or even very reckless, even when it comes to making bigger projects. We think that it’s important to be that way if we want to carve out our place in Canadian cinema.

SCOPE: A movie like Out in That Deep Blue Sea, which doesn’t really have a narrative and has a very slow-burn approach to character and exposition, is sort of a reckless film, even if the filmmaking is very controlled.

RADWANSKI: I thought everyone would think that I was crazy. When I was pitching it, it sounded nuts. It was right after Princess Margaret Blvd., which I thought most people had thought was good, and I’d be describing the new one and talking about how it was going to follow this depressed real estate agent, and that was it. I would see it in peoples’ faces, even the actors, like “what’s this about?” Green Crayons was maybe about showing people that I wasn’t insane—it was a little more straightforward. But then even as I was making it, I felt trapped by it at times. And I think I’m pushing against that with the new film, which is just as up in the air as Out in That Deep Blue Sea. I feel like each of my films attacks the one that came before, or constitutes some kind of response.

MONTGOMERY: To me, the most important thing in the relationship between the producer and the director is the right amount of trust. When you work like we do, you know that each film is going to involve a leap at some point. When Kaz talks about feeling like he was sounding crazy when he pitched Out in That Deep Blue Sea, I think it’s true, at a certain level. But it’s also what excited me about it, trying to see past the fear and to figure out what could come out of that kind of recklessness.

SCOPE: Is MDFF actively trying to cultivate relationships with other young filmmakers, like you have with Antoine Bourges? Is the idea to build a sort of filmmaking stable, based in Toronto or dispersed across Canada?

MONTGOMERY: We’re not searching people out, or pursuing them, but we welcome the chance to work with interesting directors. We want to make something larger in the Canadian film landscape. We want to keep our options open, and our eyes open. The nature of the production cycle is that you can work on something for a really long time and still have opportunities to get involved with other projects. We want to constantly be producing. We’ve done four shorts in the last four years, and we want to maintain that pace and that rigour and that intensity.

The MDFF showcase screens at Toronto’s Royal Cinema, 502 College St.West, on Wednesday, May 18th at 7:00pm.

Adam Nayman