Dragonfly Eyes (Xu Bing, China/USA) — Wavelengths

By Robert Koehler

Anticipating the current political moment of a fake US president attacking perceived enemies as fake, much of which is triggered by a culture drowning in simulacra, conceptual artist Xu Bing’s first foray into cinema seems like an ideal Chinese response to the madness. The result of a massive, years-long project to compile, select, and mould thousands of hours of surveillance footage from across mainland China into a deliberately outrageous narrative, Xu’s meta-video work comments continuously on its own fakery—a fact evidently lost on most of the trade critics, who lambasted and seriously misunderstood the movie at its Locarno premiere.

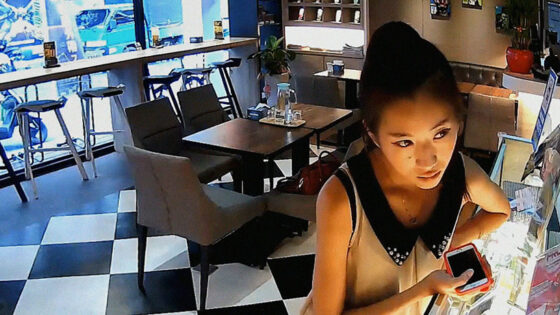

Such misconception might be wiped away at TIFF, where Dragonfly Eyes has aptly been slotted into the Wavelengths program. The screenplay, by poet Zhai Yongming and writer Zhang Hanyi, supplies dialogue and a basic narrative framework for the footage, which largely observes Chinese citizens and workers in a vast range of settings, from dairy-cow factories to cheesy motels to plastic-surgery clinics. The latter is crucial for the central character Qing Ting (or “Dragonfly,” voiced by Liu Yong Fang), who jumps from a respite at a Buddhist temple to work in the dairy factory and a dry cleaner’s, while befriended by a mysterious dude named Ke Fan (voiced by Su Shang Qing). After many disappointments and failures, Qing Ting concludes, “In this society, you either need to change your mind or change your appearance.”

Her physical transformation into online music celebrity Xiao Xiao is obviously absurd, but the point isn’t grounded in dramatic or psychological credibility as much as in a fable’s logic—the fable here revolving around the extremes that people may go to transform their sense of reality and trade it in for something that may itself be fake, and also substitutes for reality. This hall-of-mirrors, internet-era logic carries its own traps that the characters walk right into. But for anyone who’s spent some time in contemporary China, the tale spun by Xu, Zhai, and Zhang is genuine enough, since it is effectively as true as the many cutaway clips of brutally violent footage of building collapses, plane crashes, traffic mayhem, and the daily chaos that’s a regular part of living in the Middle Kingdom.

Robert Koehler