Breathing Chasms: Rita Ferrando’s Ikebana

By Saffron Maeve

“Soil does not come to life of its own accord.” So says Rita Ferrando in Ikebana (2021), a poetic documentary short about ecological temporality and the Japanese art of floral arrangement, which screened at IFFR earlier this year. The sediment is instead churned into existence by decomposing trees and heaps of fallen leaves, a bodily offering from the dead to the living. One might characterize ikebana in similar terms, as an age-old artform beholden to formal precepts—minimalism, asymmetry, graceful shapes and lines, harmony, and so on—emerging by design from centuries of tradition. Interestingly, then, Ikebana is more formally ambitious than the artistry it surveys, compiling distorted narration of texts by artists Ikenobo Sen’ei and Katagiri Atsunobu, film footage, and vivid cut-out animation to both reappraise and commemorate the discipline.

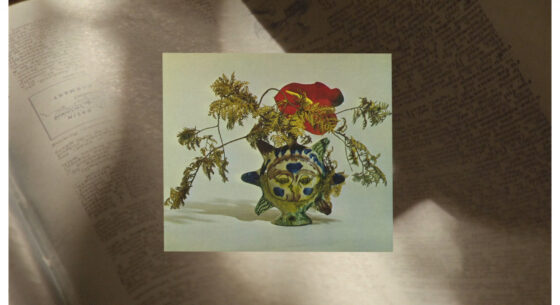

Ikebana reached its first zenith 500 years ago and existed some 500 years before that, beginning as an artistic offering to gods at Buddhist altars, then as a ceremonial practice encouraged by various shogun, and now persisting as an extant pedagogy. Artists use vessels, shears, and kenzans (“sword mountains”)—lead plates with brass bristles to fix the flowers in place—to narrativize their displays, consigning representations of past, present, and future to their beautified florets. As the filmmakers declare in warbled voiceover, ikebana does not strive for the imitation of nature, but its recomposition. The effect captured on film is hypnotic, with gauzy footage, glacial dissolves, and a lulling score by hyperpop musician Casey MQ to seal the sense of nostalgia.

A clear point of reference for Ikebana is Teshigahara Hiroshi’s 1957 short of the same name, which observed the Sogetsu School of Ikebana, of which the director’s father, Teshigahara Sofu, was the grand master. Shots of labouring florists and their careful fingers blur into those of viridescent ponds and abstract arrangements. A certain sentimentality—of ancestral ties, artistry, and the natural world—arises in the process, recaptured fluently in Ferrando’s work, which preserves this historic bent while also modernizing the practice. Where Teshigahara veered more scholastic, Ferrando and her collaborator, animator Lily Jue Sheng, favour a meditative, mystical approach. Their Ikebana is more homage than spiritual sequel, with Sheng’s animation reifying the practice’s idiosyncrasies: brightly hued, amorphous renderings of vases and foliage, folding into themselves like matryoshka.

Ikebana deals in the invisible as much as it does the ornamental, assuaging our unconscious desire for aesthetic rupture. A blunt interruption of the natural process, ikebana conceives a tableau of its decomposing subjects, in which the space in and around them is a meaningful part of their assembly. “A chasm appears,” says the director in voiceover as the camera observes a primped Strelitzia display sheathed in plastic wrap, then a microscopic collage of plant parts overtop forestial footage. The imagery is not simply a reminder of the plant’s displacement, but also of the temporal gulf which such an act compels—rifts in memory glossing a time-honoured practice, materialized as the space between the completed ikebana and the earth from which it emerged. As the filmmakers put forth, we can thus see the invisible and hear the inaudible. The purl of petal and plastic is not unlike soft skin on celluloid, a kind of tenderness translated through cuts. Committing ikebana to film, with all its folds and tidy rhythms, is itself an act of recomposition, compounding the methodologies of filmmaking and plant preening. Both vocations redecorate their subjects by way of constructed ephemera for a discerning audience. Film abides where flora cannot, preserving the art long after the plants wilt and shrivel, although one day it too will come to dust. Ikebana understands its crops and chasms well, and envisions their future amid the present and an ancient, though not outmoded, past—like well-trudged soil turned over again for a new seedbed and a second, tenth, or thousandth life.

Saffron Maeve