The Battle of Waterloo: Matt Johnson and Matt Miller on BlackBerry

By Adam Nayman

A semi-scenic, mostly horizontal non-metropolis located about 100 kilometres west-southwest of Toronto, the city of Waterloo (pop. 121,000) has earned a reputation as the Silicon Valley of the North—a close-knit network of tech companies and think tanks encircled by university campuses and a disproportionate number of insurance firms. The latter pile-up is a peculiarity that has led to the city also being dubbed (a bit less sexily) “The Hartford of Canada,” a reference that might have made Matt Johnson’s mid-’90s civic time capsule/corporate origin myth BlackBerry even funnier than it already is. It’s hard, though, to imagine anybody (including the lyricists of ABBA) improving on the script’s best line, which gets shouted proudly by local antihero Jim Balsillie (Glenn Howerton) at a moment of truth in the NHL head offices: “I’m from Waterloo, where the vampires hang out!”

With his gleaming bald pate and dead-eyed stare, Howerton’s incarnation of the infamous Ontario businessman Balsillie—who became a household name around here through his very public and ultimately failed attempts to shanghai a hockey franchise to the steel town of Hamilton—does indeed look a bit like a boardroom Nosferatu. Elsewhere, this sleek, toothy predator is referred to as a “shark,” which makes him all the better equipped to maul the “pirates” poised to shake down the shallow end of the late-’90s internet start-up pool. Balsillie doesn’t like the geeky non-entities pitching him on a combination cell phone/handheld computer, but he hates the idea that somebody else might get rich off their scheme.

Howerton’s 40-proof, rageaholic performance skirts caricature but comes out the other end as a psychologically deft tour de force. This loosely fictionalized version of Balsillie, whose seething, pent-up contempt for partners and competitors alike emanates from some darker place (maybe even subconscious solidarity with his geeky new underlings) is a memorable and malevolent creation—the closest thing Canadian entertainment has had to a Gordon Gekko since the glory days of Traders. Inevitably, Michael Douglas’ Reaganite bloodsucker gets invoked in BlackBerry by a character played (just as inevitably, and beneath a Karate Kid–ish headband) by co-writer/director Johnson, who slyly exploits the current non-visibility of BlackBerry Limited co-founder Douglas Fregin to insert a barely veiled version of him at the company’s primal scene. Johnson’s Doug is a pop-cultural sponge whose vision for BlackBerry mostly involves eating pizza and watching Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) or They Live (1988) with the boys; suffice it to say that Balsillie, who is, existentially speaking, all out of bubblegum, is not amused.

Rather than presenting a tonal problem, the wild contrast in acting styles between the technically adroit It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia veteran Howerton and Johnson—who’s been riffing on this same hipster-doofus persona for almost 20 years, since his YouTube start-up Nirvanna the Band the Show—is evocative of the deeper, generational tensions of the story being told, as is the fact that Doug’s colleagues are played by various semi-luminaries of the Toronto film scene. In its tale of self-styled keyboard warriors crashing the gates of industry—a narrative freely adapted by Johnson and producer Matt Miller from Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff’s 2015 bestseller Losing the Signal—BlackBerry unavoidably echoes The Social Network (2010), still the gold standard for millennial docudrama, in spite of its ultimately shortsighted Sorkinisms about the Real Meaning of Facebook.

David Fincher has said that his goal in dramatizing the rise of Mark Zuckerberg was to make “the Citizen Kane of John Hughes movies”; a better way to describe the final product might be as a spiritual remake of Revenge of the Nerds (1987), with beta-male shut-ins remaking the global village in their image. BlackBerry takes certain of its cues from Fincher, and amusingly bypasses Sorkin’s misogyny by having no female characters of note whatsoever. But BlackBerry is closer in spirit to something like the Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), a tragicomic picaresque about the guys who ended up being nothing more than the opening act for the iPhone. Much of the film’s two-hour runtime (which will see it divided into three parts after theatrical release for an eventual airing as a CBC miniseries) is taken up by the culture war waged inside the dingy, mall-front offices of Research in Motion, where Doug senses his powers waning as consigliere to his old pal, electronics wiz Mike Lazaridis (Jay Baruchel), in the wake of Balsillie’s one-man hostile takeover. Doug’s desire to keep things “real”—i.e., keep playing in a perpetually cash-strapped Never Never Land with the other lost bros—is, finally, just as solipsistic and selfish a methodology as Balsillie’s bombastic tantrums. Baruchel’s performance is a little too mannered (and his faux-grey hairdo a little too sketch-comedy false) to fully sell his character’s pains at ending up wedged between a rock and a hard place, but Mike’s basic dilemma is still absorbing: what if it’s not failure that he’s really afraid of, but success?

This is a question that resonates in the larger context of Canadian cinema, where success is always relative and the tendency to grade filmmaking on a curve is real. In a glowing Globe and Mail profile published after BlackBerry’s Berlin premiere, producer Niv Fichman—a longtime Canadian film-industry power player who’s worked with every high-end filmmaker in the country, from François Girard to Paul Gross —praised Johnson for being “anti-establishment.” Leaving aside the fact that Johnson has made a congenital habit of publicly mocking Fichman’s friends and peers (to the point of calling for their heads, circa the imbroglio over Johnson’s school-shooter mockumentary The Dirties [2012]), “anti-establishment” is an interesting way to describe a filmmaker whose eyes have been on the brass ring (such as it is) for a while now.

Hitting the big time has been Johnson’s theme ever since he and his onscreen straight man Jay McCarroll schemed about playing the Rivoli on Nirvanna the Band the Show. In Operation Avalanche (2015)—a period thriller famously shot on the sly at NASA’s headquarters—the director filmed himself, in character as an overbearing auteur named “Matt Johnson,” literally shaking hands with Stanley Kubrick (beating Steven Spielberg’s Fordian Fabelmans gag to the punch). Not even Xavier Dolan can match his Anglo-Canadian counterpart when it comes to self-mythologizing—although he does, to this point, have him beaten in terms of box-office receipts. Among other things, BlackBerry represents a literal and figurative investment in the future-present of Canadian cinema by an establishment that’s surely more interested in a definitively figurative return. But now that he’s arrived at the point of commanding an eight-figure budget, Johnson, Miller et al seem interestingly torn between their roots and their ambitions, and more specifically between realizing the latter on their own (Canadian) terms.

The money is very much onscreen in BlackBerry,but mostly in the service of the same scrappy tactility that is Johnson’s stock in trade. One case in point would be the agile, alert cinematography by Jared Rabb, which keeps subtly shifting distance and focal length to probe through strata of analog clutter—the right look for a narrative about the fateful intersection of physical and digital engineering. The cutting, by Curt Lobb, is swift and propulsive while imbuing a modest but real sense of sweep; the soundtrack is loaded with expensive Big Shiny Tunes that pull double duty as period signifiers and subtext generators. There’s plenty of Canadiana, too: the Matthew Good Band’s combustible “Hello, Timebomb,” about the Devil hanging out at Radio Shack, could have been written about Balsillie himself.

In a scene destined for YouTube supercuts, Howerton demolishes a payphone, Barry Egan–style, while howling at his subordinates that the three reasons BlackBerrys get sold is because “they…fucking…work.”Leaving aside the cleverness of the conjoined conceptual-slash-slapstick sight gag—telecom is dead, long live telecom—the larger idea is suggestive of the collateral damage that goes into any act of creation: the proverbial omelette and the proverbial eggs. It’d be a stretch to say that Johnson’s parable about the fragile relationship between risk and innovation works on an emotional level (there’s nothing in the film to rival Jesse Eisenberg’s lonely master-of-the-universe arc in The Social Network clicking unrequitedly into the void), but it’s hardly a glib or cynical movie, nor is it an impersonal one. In showing how hard, fun, and downright unlikely it is to make something capable of penetrating a crowded and indifferent marketplace, Johnson is allegorizing his own semi-popular filmmaking practice at least as smartly as in his more explicitly self-reflexive mock-docs. This is the first of his proudly callow movies to grapple with themes of maturity, nostalgia, and perspective—the logical next step for an enfant terrible hypothetically within spitting distance of a mid-life crisis.

BlackBerry ends with an image that brings these anxieties into focus while still allowing for some ambivalence. It’s a goofy movie that’s smart enough to know that innocence and experience are not pure states, any more than are failure or success; at its core, it’s a film about contingency, and, as such, it’s a clear-eyed piece of work. The irony in BlackBerry is that even after finding a way to literally put the world in the palm of their (and our) hands, the RIM guys lost their grip—the brass ring isn’t just shiny, but slippery. In a country whose filmic output is defined by different shades of self-deprecation, it’s refreshing to see a filmmaker who’s thinking about reach and grasp.

Cinema Scope: My first question is how much deep, rigorous research did Matt (Johnson) do to play Douglas Fregin?

Matt Johnson: We adopted the philosophy of, show up day one, no rehearsal, and play it as it lays.

Scope: The fact that you have a character who was at the centre of BlackBerry but isn’t public-facing in retirement was a big help to the movie, as it lets you stage one sort of film inside of another.

Johnson: It helped a lot. It was a strange conundrum with this picture. We’re making a broad historical comedy in our own style, and trying to make it personal and fit with the canon of our previous work, and it was really only in the margins of the book where the character of Doug was being alluded to. But it was enough that Matt Miller and I were like, well, this guy Fregin was the social connector of Research in Motion; it seems like he had very little to do with the technology side of the product. But he’s a founder, and he stays with the company until 2007. It spoke to the idea of this nostalgic sort of guy who’s there from the beginning—a throwback type that I really understood.

As soon as we saw that as the place for “Matt Johnson” to exist in the film, the rest became clear. I’m sure it’s not lost on you that in some ways, the characters in this movie aren’t really building a smartphone: they’re independent filmmakers who have success when they’re young, and it changes everything. The alienation that ends up affecting the team is very much like what was happening in our own lives.

Matt Miller: I think Matt hit the nail on the head. When we were first brought this project by Niv Fichman, it was just supposed to be a writing job. We read the book, and right as we were breaking it down to adapt it, we realized we also had to make it. So that let us write it a bit differently. We didn’t always know that Johnson was going to be in the movie, but we did start to get excited at the idea of this Trojan Horse thing. That’s also why we cast the engineers in the film the way we did, with all these people from the Toronto film scene—the dynamic felt really resonant, with Doug as this ringleader figure, at the heart of it all. Compared to some of our other films, Matt’s at the margins of this movie, but he’s still there and it felt familiar for us.

Scope: What Johnson said about allegorizing your own experience is interesting, because it’s the same thing David Fincher mentioned about The Social Network:that he saw the start-up elements of Facebook as being really similar to his experiences in the ’80s with Propaganda Films.

Johnson: I think one of the keys to a movie like The Social Network is that it doesn’t feel impersonal or judgmental. Fincher’s treatment of Zuckerberg was one of the main things we took from that movie: not just making an anti-capitalist screed about how stupid and misguided BlackBerry’s founders were, which is the easy thing to do. I think we give the characters their due, including Mike Lazaridis, who gets to return in the end to this innocent childhood tinkering, which is beautiful in a way. I watch the final frames of the film and I feel like he looks happy, just fixing things. What I mean is, we weren’t interested in just making fun of the characters, or having it be a cautionary tale about not ending up like them, because we love them. We love all of those guys.

Scope: The idea of “anti-capitalist screed” is interesting, in the context of this being a relatively big-budget Canadian movie. Beyond the fact that you’re now working closely with the kinds of producers and funding bodies you used to take shots at, there’s a tension between the smash-and-grab filmmaking you guys made your names with and the expectations that come with more resources. What does it mean to be working with what is basically a blank cheque, at least in Canadian dollars?

Johnson: It’s blank-ish. There are maybe three or four decimal places that are blank, and the rest is pretty clearly inked. But yeah, you’re describing the central tension of the production, and to put it in plain language, the more money we get to work with, the fewer tools we have. You wouldn’t assume that, but it’s true. I mean, even just dealing with actors unions—we thought it would be magical to get all these Toronto filmmakers to play the engineers, but it was like pulling teeth. On one of our older movies it would have been a no-brainer, but it was like pulling teeth for Miller.

The transition you’re talking about—about working with Telefilm Canada and the larger system—has pivoted a lot of the frustration and realigned my vision for the future of Canadian cinema. I think that some of the people who’ve come before have been content to (to use a line from the film) do “good-enough” filmmaking, and never really challenge the status quo. So there’s this carcass of dinosaur bones that we’re trying to make movies underneath, and it’s hard to manoeuvre from there.

I’ll say that there were other movies shooting around the same time as ours, with some of the same crew, and I spoke with the filmmakers and they were having hellish experiences—they couldn’t get anything done. I asked if they argued and just said they wouldn’t do it that way, and they said no, their producers told them it’s always been this way and it’s not going to change. I said, that’s your first mistake. The thing I kept saying while making this movie was, “I’m not doing that,” and Miller will tell you there were probably 300 times when we were told, “You can’t do it this way, because it’s never been done this way.” My refusing to agree with that is why the movie kept moving forward, and why it feels as free as it does.

Miller: My job was really to insulate Johnson from as much of that as humanly possible. The less he knew about what was going on, the better, because it would have made him really upset and distracted him from the very big job he had on set. The only reason the movie was successful, though, was that all of the department heads were longtime friends and collaborators. If you had watched us shooting, it would have felt more or less like being on set for Nirvanna the Band the Show or The Dirties: it was the same people doing the same jobs. Maybe Jared Raab had a fancier camera in his hand, or some better tools, but we fought to keep our crew small. Every time you add somebody to production, it complicates things—suddenly you need to feed them, and transport them, and things get out of control. We did a lot of things to stay true to our roots, and so there were times where we’d be a bit more run and gun, or shoot in places where we didn’t really have permission to be there.

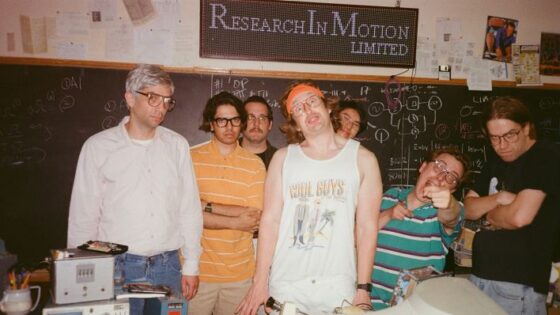

Johnson: It’s no mistake that in the film, as RIM grows, they lose what made the original company magic. That’s why the film ends with that image of the guys in the ’90s. The whole reason the product was what it was is because of the spiritual magic of the original team, and, after that, things were just running on fumes. It was all just the dissipation of that initial energy.

Scope: It’s interesting that that photo is at the end of the movie, because it feels like something has truly been lost at the end. I wonder if that’s about you guys as filmmakers as well?

Johnson: None of us could explain why that photo was so powerful; it was more trite, like, “look how far they’ve come.” It was originally placed right after Michael Ironside’s character shows up and there’s the White Stripes montage, but our editor, Curt Lobb, said it belonged at the end of the movie. I can’t even explain the feeling it gave me the first time I saw it. Like: did they win? Or did they lose? Was this all worth it? Was this for the betterment of society, or for themselves?

Scope: You mentioned the ’90s setting and nostalgia, and it strikes me that, starting with the BlackBerry itself, this is a very analog movie: very tactile, very physical, lots of literal assembly and breaking apart. It was maybe the last moment where a tech pitch had to even have a solid object in order to get over, right? Or when Doug goes to Best Buy and the team is just lashing all these bulbous, handheld gadgets together…

Johnson: We always try to play with the idea that the camera itself is a tool that the audience feels and understands. This is a huge topic and I could talk about it for hours, but it’s like when you watch this movie, the camera is suddenly heavier at the beginning, because it’s an older era. The further back we go in history, the heavier it gets: on Operation Avalanche we were taking everything from Haskell Wexler, from the lenses to the weight of the equipment. Audiences subconsciously feel the weight of the camera and the intelligence of the operator, and whatever era you’re in—VHS, Betacam, DV, mini-DV—each has its own cinematic language. The way the camera moves on the shoulder of the operator is, in a very McLuhanish way, what you’re actually watching. Those are the rules. Our movie begins in the VHS era, and we had to reverse-engineer those sensations. Jared found these rubber-ball tripod heads that you could use to mount the camera, and they’d move like they were from 20 years ago. And then, as we went along, we kept gradually deflating the heads and moving towards a more stable mount.

Scope: The era-switching in BlackBerry is subtler than in, say, Steve Jobs (2015).

Johnson: That movie tries to hold the hand of the audience in a way that is weirdly anti-Jobsian. Jobs was a master of having a technological experience be seamless, so that the user doesn’t realize it. What got the audience here in Berlin was when Mike opens up the BlackBerry Storm case, there’s a CD in there—you need instructions to wield the thing. Whereas you open an iPhone and it’s just the device, and it teaches you how to use it. The product explains itself.

Miller: You brought up Steve Jobs—we watched that, and The Social Network and Moneyball (2011).We always said, “Wouldn’t it have been great to just have Steve Jobs be set inside the garage?” That’s why we spent so much time in BlackBerry at what we called “RIM1,” the office over the Shoppers Drug Mart. That’s the ’90s we grew up in.

Scope: The Shoppers fulfills the Drake-ian prophecy of “started from the bottom now we’re here.” I want to get to more CanCon stuff in a minute, but let’s talk about Glenn Howerton, who’s playing the first adult in any of your movies. I mean, the grown-ups in your movies are like the parents in Peanuts, so this is a very different dynamic. I felt like this version of Jim Balsilie hates the geeky teenagers he’s gotten mixed up with, but that it’s also self-loathing. He recognizes himself in them, and he hates that.

Johnson: There’s a reason he’s bald! He’s very carefully cast. Miller and I talked about it and we thought that what would make the movie really great would be having somebody on set who we were all afraid of. Not the character—somebody who we were really afraid of, who people will respect and defer to in every instance, more than to me. Somebody I’ll have no power over, because he’s had 15 seasons of the most successful comedy series ever.

In truth, Glenn doesn’t find me funny. We’re friends and we get along great, but he wasn’t intimidated by us or the work we’ve done. And he had no interest in the things that the “Research in Motion” side of the movie were about. None.

Miller: I can give you an amazing example. The first time Jim arrives at RIM, we intentionally never introduced Glenn to the engineers. We never showed him the set. So when he comes to the door and sees Matt with the plunger in his hand…he’s a brilliant actor, but it’s real. He’s seeing these things for the first time, and it’s like day four of production and he’s thinking, “What the fuck did I get myself into with these guys?”

Johnson: He said it to me! He said it to me openly! After those first takes he pulled me aside—and, again, this guy doesn’t joke around, ever—and he asked for a private conversation. And he said, “You told me that the tone of this film was grounded.” It was a threat: he was saying it right to me, you know? I had just met this guy. Glenn was very open with me that he wanted to do something where he would be taken seriously. I see the role as funny, and I told him that he was going to be the funniest guy in the movie. He said he wouldn’t play it funny and I said good, because that would be even funnier.

Scope: I saw Jim as thinking he has to scare these guys, or else they’ll just make fun of him. It’s like when a coach loses their team: respect degrades into mockery.

Miller: You can see it in the scene where he goes in and tells the guys, “You need to sell half a million BlackBerries right now,” and in the shots of the sales team, they’re scared and they start laughing as a defense mechanism. That’s very real.

Scope: Balsillie is such an interesting figure: a Canadian master capitalist, or maybe a Harper-era archetype. But to be so pushy, and to throw your weight around like that, isn’t a very Canadian quality.

Johnson: Every piece of behaviour I saw from Balsillie struck me as he was trying to do his best impersonation of an American. There’s a lot of Wall Street (1987) references in the movie, also Glengarry Glen Ross (1992),and we saw it as writing a character who thought this was how Americans actually are, all the time. That helped us to understand him. It’s coming from this Canadian inferiority complex: he’s not exactly poised to inherit the world. He gets fired for wanting too much, in a way—for wanting what he thinks is the right thing. All it does is spur him on to be more American. The self-hatred comes from seeing other people like the guy in his first office, Callahan, and thinking, “I hate that, I’m not going to be that.” He sees Americans and he hates them, so he decides he’s going to beat them. It infects everything.

Scope: It’s crucial that you don’t have any kind of primal scene or origin myth; his hatred is credible and fully inhabited without ever being explained.

Miller: We toyed with those ideas. We had a lot of different possible openings, like him getting kicked off his childhood hockey team, or not getting picked to play at recess, or flashbacks to him getting beaten up. Another thing we had for quite a while was Jim trying to hide his Canadianisms, but we decided the audience was going to get it already and we didn’t need to do that.

Scope: Have you guys heard from Jim Balsillie yet?

Johnson: My secret intuition was that he was going to love the film. He was going to see it as, “Oh, they made me a movie star.” The author of the book we based the script on, Sean Silcoff, speaks to Balsillie regularly on the telephone, so he was kept up to date on everything. We’ve heard he has an enthusiastic curiosity. I don’t have a psychological take on the real guy; I only have what Miller and I wrote based on transcripts of conversations, all secondhand. What the real guy thinks, I have no clue.

Miller: Our plan is to reach out when we get back to Toronto and arrange a screening. In many ways it’s a sympathetic portrait that humanizes him a way our media hasn’t.

Scope: I promise you both that if you had $900 million you would no longer be human to me.

Miller: I’d get us courtside seats for the Raptors.

Scope: I know the film is going to air on CBC and stream on CBC Gem later this year as a miniseries. Was that a consideration for the overall structure?

Johnson: Yes and no. We thought about dividing it into three different eras, but we moved off of that as the film took shape. It’ll be more like the final cut just split into three, but we have a lot of unused stuff that will be in the miniseries.

Scope: You guys cast Canadian-born actors like Michael Ironside and Saul Rubinek in key supporting roles, which again seems tied to the overall project of the movie: this tension between Canada and the US, in this case between Canadian cinema and Hollywood.

Johnson: I think it speaks to an era when there was an excitement about actors coming up in this country—those guys embody that, and they still have it. Now, in English Canada, it’s a bit like there’s no actors. Where is the troupe?

Scope: Well, this is a big talking point: the idea that a lot of the best movies being made in this country—whether you want to call them microbudget, or independent, or hybrid, or whatever—don’t use actors conventionally, and don’t use narrative conventionally either. These are films whose styles are dependent on non-actors or improvised dialogue, or something along those lines. It still feels like a byproduct of certain things in Canadian film history: the documentary tradition and the lack of a clear narrative model beyond Hollywood. So you’re in an interesting position, which is somewhere between an emerging vanguard and a mainstream that’s still a bit ill-defined.

Miller: I think that the criticism of our film will be from people who don’t get it or connect with it and think it’s just another cookie-cutter biopic of a tech start-up. Obviously, we don’t feel that way. We took that model and fused it with our own sensibilities and style and taste. The criticism could be that it’s a sell-out, that it’s an American-style movie made in Canada. But it’s a Canadian story, based on a Canadian book about Canadian subjects, made with an almost entirely Canadian cast and crew and financed almost entirely in Canada. We shouldn’t feel bad about wanting people to see our films, right?

Johnson: Hold on a second, Miller. You said before that a lot of the cinema being made right now is in the necessity-is-the-mother-of-invention mold. I think what we’re seeing now is people making the sorts of movies that can be made right. There aren’t a lot of actors, there aren’t a lot of writing programs…our film schools are stuck in the ’80s. Miller and I are inside these institutions; we’re teaching at York University.

Scope: That thing about being inside of the institutions is pretty ominous.

Johnson: The call is coming from inside the house! But there’s a reason now that we have a search for narrative, actor-driven, beat-to-beat storytelling. There’s no ground for those flowers to grow. We’ve managed to culturally eradicate the fertile ground for this kind of filmmaking.

Scope: I don’t know if you guys can really be a model for anybody else. I do think there’s a history of Canadian filmmakers trying and struggling to level up, for whatever reason. But eventually one of these movies is going to break out, too.

Johnson: Time will bear it out. I mean, again, this film could really, really, really fail, especially with domestic audiences. There’s the chance that our style is way too alienating, and an echoing mass of fiftysomething Canadians will be like, “I can’t believe they let these guys make the movie about BlackBerry.”

Adam Nayman