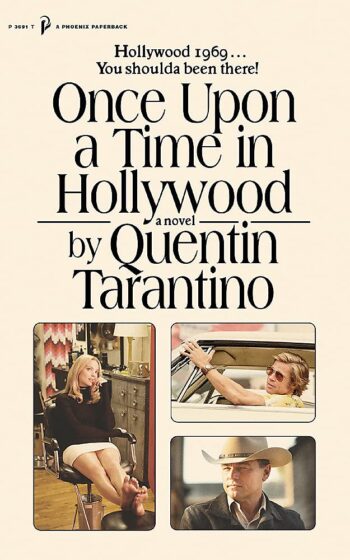

Revising Revisionism—Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: A Novel

By Adam Nayman

“This is the unwieldy version of the movie,” said Quentin Tarantino on the Pure Cinema podcast in June about his new 400-page novelization of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (2019). “Unwieldy” is indeed the right adjective for QT’s new make-work project, and it’s also probably the last word on his creative sensibility. The bantering gangsters so loquaciously comparing tipping etiquette at the outset of Reservoir Dogs (1992) were signal figures, not only in terms of their mutual look, attitude, and affect—all cool, as Jules Winnfield might say, as a bunch of Fonzies—but also in their penchant for an aggro digressiveness that would in turn become the lingua franca of indiedom. The slow rotation of the camera around the gang’s diner-table confab cinches the joke of men talking in circles to avoid getting to the point: “You gonna bark all day, little doggie, or are you gonna bite?” asks Michael Madsen’s Mr. Blonde later on, limning the distance between word and deed, between yapping and action.

Back in 1992, it was still possible to wonder whether Reservoir Dogs’ profane talkiness represented an antidote to the PG-rated, FX-driven cinema of the ’80s or the overindulgence of a tyro willing to kill pretty much anything except his darlings. Thirty years, nine (and a half) features and countless piquant, run-on monologues later—think David Carradine extemporizing about Clark Kent’s wardrobe in Kill Bill: Vol 2. (2004), or Christoph Waltz deconstructing Aryan mythology in Django Unchained (2012), or pretty much all of The Hateful Eight (2015)—Bigmouth has struck again and again. Tarantino straddles the landscape unchallenged as American film’s ruling auteur-emperor, his cinema of dialogical pyrotechnics—of, we might say, bark as bite—having displaced his predecessor Steven Spielberg’s Empire of Light. Meanwhile, his unwieldiness, exacerbated since the death of his marvellous editor Sally Menke, is neither a bug nor a feature, but an operating system unto itself. Bloat is Tarantino’s inherent vice: his primary talent—an entity as massive and multifaceted as (and inseparable from) his grandstanding ego—lies in his ability to eventually steer things toward equilibrium.

Exhibit A: Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, an undeniably distended yet largely beguiling exercise in goldbricking, whose middle hour is mostly devoted to watching characters running unhurried errands around town (including locating parking spaces). “You shoulda been there!” crows the movie’s tagline, and Tarantino’s nostalgia trip is so besotted with its El Lay setting and Summer-of-’69 timeline that it doesn’t want to say farewell (160 minutes makes for a long goodbye). Instead, the movie meanders, sometimes beautifully, sometimes boringly, serene in the knowledge that in the right hands these two qualities can be indivisible. The film’s spaciousness is pressurized not only by our knowledge that beach boy Charles Manson is dangling the Sword of Damocles over his neighbours, but also by the dual tension lurking in all of QT’s work, be it good, bad, and/or ugly: the dialectic between an ex-tape-slinger’s smart-aleck grasp of film history, and an artist’s passionate love for and immersive submission to the medium itself.

A friend of mine liked to say that where the Jean-Luc Godard of À bout a souffle (1959) made viewers into film critics, Tarantino makes film critics into fanboys, instinctually subordinating ideology or interpretation to inventory. “Tarantino does not understand New Wave conviction,” proclaimed Armond White in 2002, although Our Bud at the Movies was, amusingly, grudgingly won over by the shamelessly reactionary sexism and subtext of Tarantino’s latest’s; until Spielberg can be made great again, his inglourious-basterd offspring will have to do. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as outrageously annotated as anything in its maker’s oeuvre, but where it surpasses its predecessors—and locates its most important visual motif—is in images of characters gazing at screens of different sizes. Some are narcissistically hypnotized by their own reflections, as in the much-memed shot of Leonardo DiCaprio’s Rick Dalton animatedly pointing out his own prime-time cameo, or the sequence of Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) taking in a cheap matinee of The Wrecking Crew (1968); others are just indulging in a bit of escapism.

For instance, it’s a pretty good existential joke that Brad Pitt’s battle-hardened, matinee idol-handsome stuntman Cliff Booth lives in a trailer behind a drive-in movie theatre, a set-up that speaks to both his larger-than-life stature and below-the-line status. In the novel, Cliff the charismatic loner is revealed to also be a hardcore cinephile, which is to say a surrogate for his creator—a decision that sacrifices everything that was so wonderfully laconic and suggestive about Pitt’s performance, with its steely yet relaxed physicality and winking, self-deprecating chivalry, on the altar of Tarantino’s jones for expository psychologizing. Onscreen, the shot of Cliff toiling shirtless on a Cielo Drive rooftop, adjusting Rick’s television antenna so that the latter can better watch his guest shot on The F.B.I., expresses something funny, tragic, and attractive about the character’s simultaneously elevated self-perception (he’s another of Tarantino’s reticent, neo-samurai supermen) and the servile fate he’s made for himself. Pitt’s priceless delivery of Cliff’s terse, it-is-what-it-is acknowledgement (“Fair enough”), which caps an extended flashback chronicling his transgressions and their consequences, and uncharacteristically for his screenwriter, evinces something like brevity-as-wit, not to mention soul.

So what is really being added to the equation when Tarantino the literary carpetbagger tells us, at great length and in a grinningly omniscient literary voice that mixes ’60s idioms with contemporary slang (just like the voiceovers in Inglourious Basterds [2009] and The Hateful Eight), about Cliff’s checkered past; or about his bloody war record; or about his acquisition of his beloved pit bull, Brandy; or about his culpability several times over as a civilian killer; or about the fact that, in his amateur critic’s opinion, Kurosawa Akira was the Man and Michelangelo Antonioni is overrated? The answer, for some (myself included), will be “Not much,” while the myriad omissions of entire scenes from the film seem calculated to make the fans of the big-screen version mad. And let’s be honest: who else is likely to make it through this thick, unwieldy book besides said fans? It’s a dangerous game to automatically impute bad faith to an artist, but there are signs of trolling afoot here. Or perhaps, if we are to impute better faith to our author, the novel could be viewed as an act of self-conscious revisionism that shows Tarantino finally, genuinely challenging a fanbase hardwired to forgive his trespasses.

To stick with Pitt’s version of Cliff, the whole point of the character’s coiled, two-fisted virtuosity—flashed most entertainingly in the notorious, discourse-mongering scene where he smacks down a cocky, Green Hornet-era Bruce Lee just for kicks—is that it comes in handy at the movie’s climax, when emissaries of the Manson family knock on Rick’s Hollywood Hills door and get their faces bashed in (and worse) by his muscular gofer. In the book, though, this climax gets reduced to a brief, almost parenthetical flash-forward located about a third of the way into the page count—a throwaway that lands with calculated impact. The relative sidelining of violence in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: A Novel—which relegates its acts of brutality almost entirely to the past, and, with one exception, eschews gory details—could be taken as a rare instance of restraint. The excess lies elsewhere, in the pounding waves of ephemera that submerge the reader at every turn: about Rick’s missed career opportunities; about the dramatis personae and behind-the-scenes politics of his new prime-time Western, Lancer; about the mirror-image hitchhiking-hippie backstories of Sharon Tate and jailbait runaway Pussycat (embodied in the film by the phenomenally elongated Margaret Qualley); about the latter’s initiation into the Manson gang; about the inner workings of the movie business at a time of paradigm shift.

This last theme is definitely central to Tarantino’s film, with B-movie star Rick’s flop-sweat anxiety over his own encroaching status as an industry anachronism generating some of that aforementioned reactionary subtext. The message gets hammered home (literally) by Cliff’s cool, spliff-fuelled obliteration of the Mansonites, youthful ciphers (played in the film by Hollywood scions) whose sociopathy gives their killer ethical carte blanche—on top of which, their deaths spare Sharon Tate (the princess in the title’s fairy-tale equation) and, in domino-like fashion, get Roman Polanski off the hook for crimes not yet (and perhaps now never) committed. Yet by excising the film’s loaded, showstopping moment of catharsis, Tarantino is not only messing with expectations, but also employing his own indelible cinematic staging as a structuring absence while feeling out another, considerably more sentimental angle of approach to the idea of generational conflict and resolution.

With this in mind, the character whose role gets inflated the most in the book is Trudi Frazer, the prepubescent grand dame (played in the movie by the then ten-year-old Julia Butters) who gives her nervous, hungover Lancer co-star Rick a combination pep talk/dressing down before shooting his scene, and then supreme validation in her assessment that his was “The best acting I’ve ever seen” once the cameras stop rolling. (“Great fucking note,” sobs Rick under his breath, in maybe the best line reading of DiCaprio’s career.) Tarantino replicates and expands this dynamic in the book so that Trudi isn’t just a miniature Greek chorus narrating and redeeming Rick’s failures, but a full-fledged, psychologically complex collaborator, and his reasons for doing so are interesting indeed.

In an interview with Marc Maron, Tarantino explained that he wrote large sections of the novel with his infant daughter in the next room. This story not only creates an unfathomable mental image of our FUBU-clad hero as Mr. Mom, but also contextualizes Rick’s affection and investment in the little girl beyond mere comic relief. A late flash-forward reveals that Trudi the burgeoning Method actress will grow into a brilliant, Oscar-nominated star, and that one of her greatest roles will be directed by no less than Tarantino himself (from a script by, if you can believe it, John Sayles). This smiley bit of self-citation intersects with another episode in which Rick, more or less accepting his fate of playing Lancer’s resident heavy, dutifully signs an autograph for a Western-obsessed kid named Quentin—which takes QT’s tendency to literally insert himself into his films and flips it from faux-Hitchcockian preening into a sweetly revealing bit of autofictional gamesmanship, a foray into an imagined yet essentially authentic primal scene.

It’s in the aftermath of signing the autograph and running lines over the phone with Trudi that the cynical, middle-aged Rick hears the call of his inner child, and the epiphany he has as a result—about the good fortune he’s had to make a life and a living out of playing cowboy dress-up—makes for a genuinely disarming bit of summation. Here, Tarantino skirts showbiz cliché without fully succumbing to it, and also accesses something that is otherwise in short supply in his rictus-grinning cinema: genuine joy, tellingly yoked to a respect for professionalism. In the end, the sullen, self-destructive, know-it-all Cliff isn’t Tarantino’s only mirror: Rick’s arc comes to stand in for a different and more endearing form of self-knowledge, one shot through with a current of gratitude. It’s a stretch to call this quality humility, such as it is; we never forget that this is a titan moonlighting. But even if, at its core, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is little more than history written by a winner—a victory lap by a scribe forever turning curlicues on his home turf—at least the author proves gracious and even humane in victory.