Pale Shibboleth: Will Hindle’s “Chinese Firedrill”

By Chuck Stephens

“There is a metaphor recurrent in contemporary discourse on the nature of consciousness: that of cinema. And there are cinematic works which present themselves as analogues of consciousness in its constitutive and reflexive modes, as though inquiry into the nature and processes of experience had found in this century’s art form, a striking, a uniquely direct presentational mode.”

—Annette Michelson, “Toward Snow,” Artforum, 1971

The greatest film ever made that you’ve in all likelihood never seen, Will Hindle’s 1968 short masterwork Chinese Firedrill is a rarely screened, never-digitized chamber piece/psychodrama about memory, consciousness, involution, set design, comic/cosmic performance, and the inscrutable experiments and sublime experiences of photo-chemical cinema as it was just a little over half a century ago. It’s a movie of a very particular sort, granular and expansive, gloriously unknowable, a relic and a revelation…and an altogether fitting place to bring this magazine to a close.

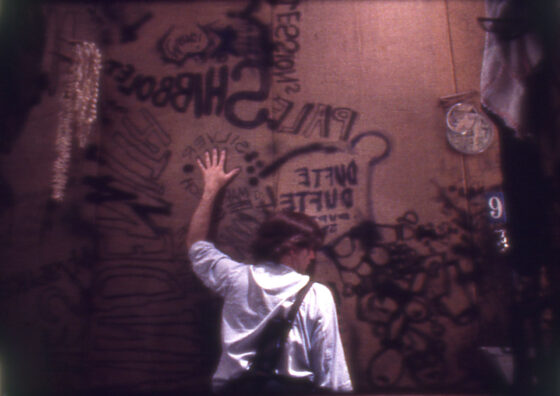

Chinese Firedrill is still what movies used to be, back when Amos Vogel published Film as a Subversive Art: something that you may have to work for years, and end up being in just the right place at the right time, to see projected only once—left afterward with only the luminosity of your memory. (You can’t download it, and you could probably count on one hand the number of times it’s been publicly exhibited in the last decade.) Professor Michelson was speaking of Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) in her protean entry into early ’70s “theory” above, but it strikes me now, 50-some years on, that she might well have been contemplating Chinese Firedrill, in which a shaggy dreamer (Hindle, in a flamboyant wig and occasional bearskin) awakens in a small and mysterious place that is almost certainly the shanty of his own mind. The walls are inexplicably covered in written-backwards graffiti: “New Brunswick,” “Dachau,” “Hairy Place,” “Japan.” Attempting certain strategies for organizing his clutter—sorting IBM cards, spilling them again, shovelling them about the hovel—the shaggy dreamer contemplates what might be his memories. Superimposed flurries of glowing fragments flood in: mother, violence, ceremonial candles, shards of coloured glass. The film is his process of making, beautifully and ever-elusively, his interiority available for all to see.

Shot in San Francisco, Chinese Firedrill is scored with sonar pings, warbly film-score exotica, and a run-on reminiscence in a rambling voiceover that evokes wartime, father, family, ethnicity, and nomadism, all in a sketchy Eastern European accent that might be a comic riff on Jonas Mekas (who’s said to have taken it personally). Figures appear: a boy bathing in a tiny tub, a shaggy doppelganger and a woman Saran-wrapped in glitter, comingling just beyond the space’s sole glowing aperture. Each visual is at once entirely specific, lustrously photographed, and limitlessly unstable. Is that bottle-shaped portal large or small? An escape hatch, a membrane, or a blockage? “Pale Shibboleth,” announces a backwards slogan on the wall; on another, a torn bit of a poster for Masumura’s Manji (1964). Everything is legible, nothing makes sense.

“Chinese Firedrill is a romantic, nostalgic film,” wrote Gene Youngblood, one of Hindle’s greatest contemporaneous champions, in his epochal Expanded Cinema. “Yet its nostalgia is of the unknown, of vague emotions, haunted dreams, unspoken words, silences between sounds. It’s a nostalgia for the oceanic present rather than a remembered past. It is total fantasy; yet like the best fantasies—8 1⁄2, Beauty and the Beast, The Children of Paradise—it seems more real than the coldest documentary.” Alas, documentary takes time, and we have none left here, so please refer to my earlier Cinema Scope columns on St. Flournoy (1970) and Billabong (1969) for more details on William Mayo Hindle (1929–1987) the man, artist, and iconic/ethereal filmmaker. Hindle’s legacy, only 11 some films, each of them rarely, if ever, seen, remains emblematic of just how expansive and exquisite 20th-century cinema truly was, and of just how deeply into that legacy we’re all still eager to go.

Chuck Stephens