Nothing and Everything: Black Zero Begins

By Joshua Minsoo Kim

The three inaugural releases from Black Zero, a new archival label dedicated to Canadian experimental cinema, are unified by their mystique and uncompromising, adventurous spirit. This new enterprise is particularly exciting because it’s supervised by Stephen Broomer, an author, director, film preservationist, and programmer who has spent many years championing the Canadian avant-garde, and he’s evidently approached this project with the utmost seriousness. Restored and presented on Blu-ray, accompanied by essays and commentaries that provide crucial context and insight, these films are here given the treatment they’ve always deserved.

The most immediately exciting work is Palace of Pleasure (1967), a dual-screen film by John Hofsess. Inspired by Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a multimedia performance he helped bring to McMaster University in Ontario, Hofsess recognized the sort of sensorial ecstasies that could be brought to his own practice. In his essay “Towards a New Voluptuary,” which comes packaged with the release, Hofsess makes clear that he values the filmic medium for its potential therapeutic properties. What “cinematherapy” entails is not some sort of ambient reverie a viewer can reside inside, but something more complex and participatory: Hofsess wants his images to “penetrate the censorious mechanisms of the mind and explode,” while the accompanying music provides an avenue to channel our younger selves, a time when we were “freer and more spontaneous.” In short, Hofsess wanted his work to have a profound impact on anyone watching, so much so that it would be impossible to distance oneself from what was onscreen. In his words, audiences would be “rediscovering their freedom.”

Such hyperbolic phrasing, especially when paired with the psychedelic films from this era, can lead to eye rolls: okay, we get it, these colours are transportive. But Palace of Pleasure is an undeniably affecting work, the use of dual screens thoughtfully considered, interacting in ways that are more playful than in, say, Warhol’s Chelsea Girls (1966). Intended as a trilogy, the 38-minute film features two completed parts, titled Redpath 25 and Black Zero (the third was never finished). Redpath 25 begins with irresistible images, enticing not just because they look stunning—a woman (Patricia Murphy) bathed in vermilion light, a metal structure twirls with a golden hue, a sexual encounter arises in the midst of reflective foil—but also because of its effective montage. Hofsess seductively oscillates between different modes, utilizing close-ups of faces, abstract colour figures, and chemical treatments of film to depict sensuality beyond direct representation. It’s not just the palpable sensation of touch that impresses, but the rhythms of every shot and cut.

While all this appears on the left channel, the right screen shows black-and-white footage of the Vietnam War, with a stationary image of a man’s face, coloured jade and looking downward, superimposed on top. If there is an anti-war sentiment here, it’s less instructional than experiential: look at this other set of frenetic images, Hofsess seems to suggest, and see that war doesn’t offer anything but drab misery. The Who’s “My Generation” plays on the soundtrack, though it acts as too neat a symbol for iconoclasm.

Leonard Cohen later arrives to read some of his poetry, his solemn tone transitioning the film from the vibrancy of Redpath 25 to Black Zero’s more serious demeanour. Here, both projections have some semblance of narrative: a woman paints, people slit their wrists in some ritualistic practice, and a couple embrace in bed as another man (a young David Cronenberg) lies on the other side. These scenes play out alongside passages with colourful geometric patterns, which Hofsess created by holding a kaleidoscope in front of the camera as footage was projected on a wall. They’re initially mesmerizing, but when he relies on them for too long, the images devolve into a tepid haze; it feels like little more than a neat party trick. It is tedious to only see these morphing colours and shapes, trusting that they are adequately prismatic. In interspersing them with other images (and with the aid of dual projection), Hofsess reminds us of the constant transformation taking place onscreen, and how everything exists as an interconnected web. The early image of a blazing rose lingers in my mind when seeing people kiss later in the film, bridging the symbolic with the real. And when Hofsess projects colourful splotches over human bodies near the film’s end, abstraction and reality finally become one.

Given how striking and varied the images are across Palace of Pleasure, it’s a shame that they’re occasionally sullied by the soundtrack. The sound of noodling guitar melodies can be hypnotic, but here it registers as unnecessary hand-holding. Still, something like the Velvet Underground’s “European Son” is mostly appropriate, its extended riffs and noisy feedback allowing the images to remain sufficiently abstract, and even helping to link the side-by-side images: the energy of kaleidoscopic colours on the left animates the slowly intertwining bodies on the right. “I’m Waiting for the Man” is an awkward choice, however, mainly because it contains too many sung words, detracting from the visuals. Palace of Pleasure ends on a perplexing note: the song plays out without any images, and we’re left listening to it in a dark room. I would love to say that reducing this multi-sensory experience into one of pure audio is a poignant distillation, but it’s really just anticlimactic.

Those wanting to be further confounded can look to Arthur Lipsett’s Strange Codes (1972), the sole independent work made by the filmmaker after he left the National Film Board of Canada. While his first shorts under the institution were sharply edited collages portraying society in cryptic manners, this 23-minute film, shot in a Toronto home, is hard to pin down. It begins with a grey screen, which turns out to be Lipsett’s own body as he moves out of the frame. Perspectives continue to shift as he reveals boards filled with drawings and notes. There’s an insistence on having the viewer decipher the significance of every clue, an idea made clearer when we see the letters “X” and “W” on different sheets of paper, recalling the evidence marker shown in Lipsett’s 1968 film Fluxes. Has a murder occurred? The film cuts to a shot of Lipsett’s body on the ground, implying as much; but then he appears in a subsequent shot, sitting up and assembling a Trojan Horse.

Strange Codes is a thrilling experience because it is maddeningly impenetrable. The title is first seen on a small note card, and then appears in larger text on a piece of paper, which is casually thrown in front of the camera. It’s not that Lipsett is being cavalier so much as setting the scene, priming the viewer for an experience that’s looser than his prior works. Given the constant sense-making of his montages, it is natural to approach Strange Codes with a similarly inquisitive mindset. We see a Tower of Hanoi puzzle with three rods, then three unmarked boxes, then a strip of paper with three words: “UMERUS,” “SATOR,” and “PARTIO.” Are all these connected? It’s never explicitly clear.

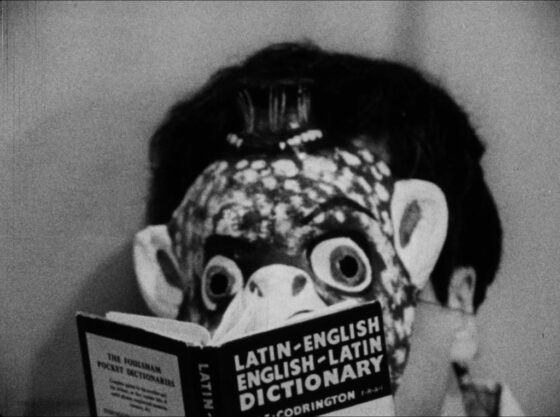

Other elements are easier to connect. A performance of The Monkey King is the film’s primary soundtrack, and its distinct fiddles, clapper drums, and small gongs suffuse each scene with a ceremonial energy. Lipsett dons a mask to become the mythical figure, and as he reads a translation dictionary, there’s a sense that he finds the creature’s powers—he can make copies of himself, transform into other animals, and travel at ridiculous speeds—as analogous to the power of both film and performance. Just as his previous films drew links between its found footage, so here does Lipsett create an expanding network with every symbol, object, and gesture.

Interspersed with the Beijing opera performance is an interview with cybernetics pioneer Warren Sturgis McCulloch, whose musings Lipsett had incorporated into previous films of his (all of them excerpted from a two-part 1962 NFB program called The Living Machine). This constant return to the material is emblematic of the inquiry at the heart of our participation in this work: we must continually probe, accepting that an infinite number of things can be gleaned from a single source. “What we lack is a logic of relations,” McCulloch explains, as if reprimanding us. “It practically does not exist.” That Lipsett puts on different costumes throughout the film, and is seen looking through binoculars and magnifying glasses, acts as a mirror: he’s engaging in the same sort of puzzling.

Strange Codes was made when Lipsett’s mental health was in decline, and responses to the film—both at the time and today—have included derisive complaints about its inscrutable nature. Perhaps in response to such incuriosity, Broomer includes an 84-minute shot-by-shot breakdown of the film on this release. It’s commendable, but feels like overkill, as if he is stripping the work of its intrigue. I prefer to approach the film somewhere between these two poles, knowing that each rewatch will reward further insight without caring for full comprehension. More than anything, Strange Codes demands your attention, asking you to understand the capacity for meaning that images can hold.

This high regard for the image is crystal clear across Keith Lock’s 1972 feature Everything Everywhere Again Alive. The work documents a year or so at Buck Lake, a locale where Lock and other artists had removed themselves from the larger world and where they lived without electricity, plumbing, or running water. We see them construct a barn, cut each other’s hair, ride on snowmobiles—at face value, this is a diaristic document of their everyday life.

In 1975, Lock explained that this work is “about human construction, human nourishment and natural processes…It requires common sense and mysterious uncommon sense at the same time.” These two sentences reveal how the film’s form and content are interwoven. One of the most effective strategies that Lock considers is sound: he forgoes any of it for a lot of his shots, allowing each image to feel even more intimate, like we’re an outsider peering into something sacred. That’s true in some sense—the freedom to live in a DIY community of this sort is increasingly difficult today, and there may be nothing more holy than the bonds that unite friends—but the images often glow with an unmatched purity. There is an astounding shot of a kitchen, where a kettle boils and eggs are cooked, that is reminiscent of Larry Gottheim’s simple, beautiful Corn (1970). I was in awe at its resplendence.

At various moments throughout the film we hear minimal, humming synth tones, which were added because Lock felt he heard such sounds coming from the images themselves. The noises somehow reduce and expand the footage at the same time, distilling them into specific moods while revealing how much more is contained therein. It’s an elegant manoeuvre that is matched by another interesting strategy: graphics (shapes, numbers, a circuit diagram) are overlaid atop images. Formally, these feel in line with works by other Canadian filmmakers like Joyce Wieland and R. Bruce Elder, and they call attention to the surface of the film plane, as if inviting us to view everything as a spectacle behind glass.

On a basic level, these drawings add another layer of intrigue to the film’s straightforward images. They also hold deeper meanings, as when a tiny circle is placed in the middle of the screen. In an interview with Lock that comes with the release, he explains that circles can represent nothing (as in the number zero) and everything (since it has no beginning or end). He also says that being outside feels a lot like this shape: open. Through its formal experiments and homey depictions of life outside, Everything Everywhere Again Alive channels freedom—it gives you a taste of it through its gentle, alluring images, and leaves you wanting more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim