Deaths of Cinema | Cork Soaker: William Friedkin, 1935–2023

By Chuck Stephens

“The path was silver, grained with streaks of rose-gray, and the walls of the canyon were turquoise, mauve, chocolate and lavender. The air itself was vibrant pink.”

Those might be production notes in the script margins of William Friedkin’s To Live in Die in L.A. (1985), one of the most garishly exhaust-plume-orange and postmodern-hot-pink cop films ever made, if they weren’t the topographical filigree of Nathanael West: a snippet from a beautiful passage in his otherwise coruscating fresco of Hollywood, The Day of the Locust. The proto–West Hollywood patina of West’s momentarily gay wilderness notwithstanding, the reality is that nothing bleeds brighter or smells sweeter under the Southern California sun than fresh bullshit wafting down through the Hollywood Hills. The stuff flourishes in the desert heat, and connoisseurs simply pluck it from the smog whenever the urge needs indulging. Friedkin—the late, great regent of serious-minded Hollywood horseshit…I mean, the director of some of the greatest commercial American cinema ever made—positively adored the stuff, and loved to let it waft around.

His finest films—Cruising (1980), The French Connection (1971), The Exorcist (1973), To Live and Die in L.A.—are lotuses in the mung, gloriously efflorescent spores on the fertilizer of innumerable Z-grade genre formulas: the good bad cop, the haunted teenager, the thin line between law and fate. There are, too, the many fecal farragoes and other misbegotten misfires he essayed: Jade (1995), The Guardian (1990), Rampage (1987)—films as maudit as they are, by a few, perversely admired. (Only the loneliest auteurist would consider rescuing the C.A.T. Squad films.) And then there was Friedkin’s love of saying, or exaggerating, practically anything, half-remembered nonsense or wholesale wishful thinking, to entertain his interlocutors. When I interviewed him in 1994 during the making of Jade, I toted along my copy of the Cruising soundtrack, which Friedkin gleefully autographed (after Mink DeVille), “It’s so easy!” Upon mentioning my love of Joe Spinell, in general and in Cruising, “Hurricane Billy” took the bait. “We shot a scene where Joe Spinell was getting sodomized with his nightstick up against his patrol car, and he’s singing ‘I’m going to Kansas City, Kansas City, here I come!’” he told me, breaking into a grin. “But we couldn’t use it.”

Of course you did, Billy. Because who cares whether that’s true or not? Whatever it is, it’s beautiful, and beautiful precisely because it’s both impossible to believe and exactly what you want to hear. Ditto stories about (and other desecrations based upon) the legendary “lost” half hour of leather-bar footage from Cruising. Legends, like loose shoes, are luxurious things. But look, I only met the man once, heard him speak live once (on stage at the DGA in conversation with Fukasaku Kinji, after a screening of Battles Without Honor and Humanity [1973]), and have listened endlessly to his raconteur-style (that’s French for “bullshit artist”) commentary tracks and interviews (many of them reified in Friedkin’s highly entertaining memoir, The Friedkin Connection), so don’t take my word for it. Here’s legendary French Connection sound recordist and mixer Chris Newman, who won an Oscar for The Exorcist, on Friedkin: “He’s honest. He’s dishonest. He tells you what you want to hear. He’s very clever psychologically; very instinctive about who you are, and who he might be at that moment.” That Friedkin told critic Mark Kermode a slightly cleaner version of that story about Joe Spinell a few years later (as he doubtless had to others on numerous occasions) only presses the point.

Indeed, it is the point—when the doubt gets so ripe you can smell it, and the ambiguity so delicious that you can’t help but dig in, that’s the very essence of Friedkin’s cinema. The French Connection’s whimpering-bang, enter-the-void ending; the ever-multiplying murderous midnight ramblers of Cruising; that classic gender-rending cheat-cut at the heart of To Live and Die in L.A.—this is the stuff that makes his movies sing. Those moments where the horseshit meets the unheimlich: a bare-chested cop fellating his partner’s nightstick, Gina Gershon fellating a fried chicken leg, your mother sucking cocks in Hell. Though a confirmed admirer of Surrealism (even Buñuel favourite Fernando Rey ended up as “Frog One” in The French Connection, only through a kind of chance encounter), Friedkin, the documentarian at heart, ruefully (and too modestly) admits in Friedkin Uncut that, “I have not been able, on many occasions, to transcend reality.” His admirers would disagree: Friedkin at his apogee can confound reality with every cut he makes. And even the casual filmgoers who’ve collectively made some of his films the most successful of all time would have to admit that when he does make the leap, watch out. (Cue high-velocity gurgitation of green pea soup.)

Friedkin always clung to his roots in describing many of his best fiction films as “induced documentary”—“stolen” shots, “natural” lighting, jockeying for camera angles like an old-school newsreel ace—and none benefited more from this rubric of a New(-fangled) Hollywood verismo than The French Connection. But that marketing angle disingenuously downplays the film’s extremely elegant and entirely classical narrative construction. Hitchcock and Welles—Friedkin never shook the precision or elegance of either. The movie proceeds on impulse and energy, street portraiture and class ressentiment, even as the dope seized at the real-life climax of Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso’s investigation is both the film’s MacGuffin and its Rosebud, the seizure itself relegated to a perfunctory title card while the film’s actual climax is as steeped in annihilation and uncertainty as the end of The Lady from Shanghai (1947) or Citizen Whatisname. The “French connection” the film makes is that Gene Hackman’s delightfully irredeemable, racist-fuck supercop “Popeye” Doyle never makes the connection: “Frog One” keeps on hopping (into the smack-addled obsessiveness of John Frankenheimer’s excellent French Connection II [1975].) In Friedkin’s Langian vision, fate itself is the only hero. A cop kills a cop, never catches the criminal, and finally darts off into a black hole of his own making—handcuffed to his bed, picking his feet in Poughkeepsie, nobody winning, a shot in the dark.

“It’s a movie about a garbage truck at dawn,” always eloquent French Connection sound designer Chris Newman recalled. “It’s a movie about seagulls in the distance. It’s about endless squealing tires, and people yelling, ‘Get out of the way!’ and banging on their cars.” Such realism-in-the-margins abounds throughout the film, with Friedkin, DP Owen Roizman, and camera operator Enrique “Ricky” Bravo (who had followed Fidel Castro through the revolution with his Bolex) “inducing” their low-budget/Big Studio “documentary” simply by pointing their equipment at the fin de ’60s city and letting the cameras roll. But the sculpted drama in The French Connection is always as tight as the drums that start pounding the instant the movie begins. Friedkin relied on Costa-Gavras’ gritty, “documentary-like” political thriller Z (1969) for the film’s pulse, and even hired that film’s secret star, Marcel Bozzuffi, to take one in the back from Doyle as punctuation to the film’s bar-setting car chase. The moment proved iconic, and everybody started going to the moon (Hello, Jimmy Webb! Hi, Three Degrees!), Friedkin and Hackman especially, who both attained escape velocity into super-celebrity status with their performances, camera fore and aft, and were duly Oscar-awarded by the Academy. Pause now to reflect on the folly of Friedkin’s early, to-the-moon choice of Jackie Gleason for “Popeye” Doyle. (Gleason eventually turned up in The Exorcist.) Billy liked to invoke the whimsy and providence of “the movie gods” when remembering his good fortunes in filmmaking, but he knew damn well that it’s often the Devil that seals the deal.

Edited at 666 5th Avenue in Manhattan, The Exorcist opened the day after Christmas in 1973 and pissed directly onto the carpet of American cinema. “Mommy, what’s wrong with me?” asks adorable little Linda Blair, who will mature before our eyes into a head-twisting, gob-hocking, priest-defiling, murderous masturbator from Hell. It’s a good question though: is The Exorcist a film about particularly traumatic female puberty in the proto-feminist early ’70s? Or is it about the free-floating ancient evil still lurking in dig sites and subways and major motion pictures? Is it a film about God and his minions fighting to redeem Catholicism in a fallen, post-French Connection world while Satan whips his tail around the culture and paints Regan’s Lolita toenails red? (Black Sabbath’s Sabbath Bloody Sabbath was released the same month.) Is it all really about purging the nightmares of Nixon and Vietnam and the ’60s and blahblahblah? Does Regan portend Reagan? You can write virtually anything you like on the inside of that pubescent belly skin and it’ll swell up and glow in the dark.

Tits and a devil dong on the Virgin Mary: the surrealist-loving Friedkin cropped the blue-sky-above portion of Magritte’s Empire of Light out of his frame to come up with the iconic streetlamp-in-the-Georgetown-night portal-to-the-pit at which Max von Sydow’s ancient Father Merrin arrives to cast out Regan’s adolescent indwellings. Friedkin remembered the raspy-throated Mercedes McCambridge from George Stevens’ Giant (1956) and Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) and brought her out of semi-retirement for a chance to chain-smoke and gargle eggs all day in order to vomit up the possessed Regan’s Pazuzu voice. (Friedkin maintained McCambridge contractually insisted on having two Catholic priests on set to offer her succour and solace between takes.) Psycho (1960) too asked the question, “Mommy, what’s wrong with me?” and Friedkin didn’t just hire Lee J. Cobb as his film’s Martin Balsam, he aped the classic Balsam-falling-down-the-stairs-while-attached-to-the-camera gag during one of Regan’s early, crushing-the-balls-of-patriarchy episodes. (Is this the moment to mention that Friedkin directed the final installment of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour? Or that Sam Raimi had stolen that same sort of sight gag from Hitchcock before Friedkin stole it back again for the parboiled Raimi–se en scène of The Guardian?)

Mark Kermode’s densely detailed BFI book on The Exorcist analyzes the medical mortification of the film’s notorious arteriogram episode in terms of a pornographic deflowering, though surely one can extend the metaphor across the entire film: “Is there someone inside you?” (That the onscreen medical attendant in that scene is played by eventual real-life serial killer and leather-bar denizen Paul Bateson would later open Friedkin up in other ways.) The power of cash compelled them: while cinema’s most famous effulgences of vomitus were barfing and blasting onscreen, Friedkin was blowing bullshit at the press, pimping the box office with patently untrue claims about the film’s production, and intimating that Evil itself had visited the set. Kermode managed to dig up an old issue of Castle of Frankenstein where the director absurdly claims that the movie’s levitation effects were achieved with a “magnetic field.” Both McCambridge and stunt woman Eileen Dietz sued the studio over Friedkin’s carnival hucksterism and his implications that it was actually all Blair, or the Devil himself, who’d been the source of their accomplishments in the film. Was the demon cast out? The Exorcist made so much money that 21st-century clowns are still cashing in. But Friedkin would never take complete possession of the box office again.

A bright kid drawn to movies as an alternate form of higher education (he never went to college), Friedkin long held that his main cultural touchstones—after Citizen Kane and Psycho—were European: Antonioni, Costa-Gavras, Lang (with whom he filmed a feature-length interview in 1974). That he might remake Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953) seemed entirely natural: an action-drenched art film about dispossessed criminals in battered and battling vehicles on a last-chance power drive. Sorcerer (1977) begins four times, in four locales, deftly sketching out four “men with no redeeming characteristics”: in Vera Cruz (a nod to French Connection’s opening assassination), Jerusalem (a terrorist bombing, shades of Battle of Algiers [1966]), Paris (gentile embezzlement served with escargot), and Elizabeth, New Jersey (Irish Mid-fellas botch a Bingo-proceeds heist due to Roy Scheider’s inattention to the road). Never mind the visage of a quasi-Pazuzu beneath the film’s title card, the devil is in the prologues’ details: a sporty hitman’s white shoes, a scruffy bomber’s white sneakers, the conscience of a poet-soldier, a bride with a black eye. Sorcerer was Scripted by Walon (The Wild Bunch, 1969) Green, a Friedkin friend since the days when they both worked on docs for producer David Wolper. The film’s silent vibe-source was Gabriel García Márquez’s magical-realist milestone One Hundred Years of Solitude, and one of the film’s climaxes evokes the marine-fossil bottom-of-the-seascapes of Surrealist Yves Tanguy.

A film about insurmountable odds and end-of-an-era large-scale practical effects, Sorcerer (named for the Miles Davis album; its original title was, or so Friedkin hilariously claimed, Ballbreaker) became the director’s magnum opus and Moby Dick. The Herzogian ambition and hubris of the production ballooned the budget and broke the production down altogether on several occasions. Nitro-loaded, jerry-rigged truck crossing a comically dilapidated bridge—the whole thing was a slapstick metaphor, held together with spit and Tangerine Dream, long before it became a throwaway gag with a snowplow on The Simpsons. But the film that resulted is dazzling ’70s cinema, a world’s-end road movie that wears its madness on its sleeve: Mad Max (1979) meets Aguirre, Wrath of God. On release in 1977, it was swamped by Star Wars and scorned by critics. Friedkin was fucked. It was the very fate Sorcerer described: recklessness and blind ambition leading directly to exile, desperation, madness. Friedkin followed with a film about the folly of sudden fortune (The Brink’s Job, 1978) and began to gird his loins for what lay ahead.

At once Friedkin’s sequel to Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963) and his prequel to Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle (1982), Cruising is not the answer to its own question: “Who is that guy?!” That quote, of course, comes from the film’s inextinguishable high point, when a very large Black man, shot from a very low angle, wearing only boots, a jockstrap, and a too-small black cowboy hat, slowly strides into a police interrogation room, and smacks Al Pacino right the fuck out of his chair. Then slowly strides back out. “Who was that fucking guy??!” An ostensibly hyper-realistic cop film/murder mystery set in the amyl nitrite–blitzed world of gay S&M leather bars, where killers kill killers, all of them dressed alike, their voices literally interchangeable (“Who’s here? We’re here”), clones of clones, a leather legion. “It’s dangerous out here tonight,” croons John Hiatt on the film’s visionary ur-punk soundtrack, “I see those vampires sucking blood.” (“I didn’t want disco filthy-ing up my picture!” Friedkin insisted.) Body parts are bobbing in the Hudson, and fresh meat Al Pacino—his character based on cop/actor/legend Randy Jurgensen’s undercover work in the leather-bar scene—is primed to go as deep as he needs to to get what he wants. “Hips or lips?” one possible Mörder unter uns (to ape the original title of Lang’s M [1931]) played by Richard Cox (that’s right, “Dick Cocks”—the film just dares you to go there) asks Pacino during their climactic assignation in Central Park’s Ramble. “I go everywhere,” Pacino replies, neatly folding his leather trousers, ready to see the world.

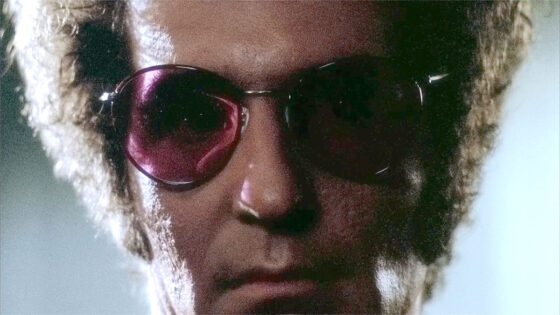

Boy meets boy, boy loses boy, boy ends up with analyst: Cruising is as a much an Oedipally-inverted Psycho (“Father, I need to talk to you”) as a Langian broodings-roman on meatpacking (or “skirt steaks,” as one of the film’s locations promises) and steak knives (a fetish resumed in The Hunted [2003]), hankie codes and subliminal insertions, Narcissus and anonym. Nightworld Manhattan seems primed to explode (it had been tick-tick-ticking since Taxi Driver [1976]), and everything on the streets is double-edged. “We’re up to our ass in this,” a wounded and prematurely aged Paul Sorvino confesses, only he’s not a member of Fist Fuckers of America—he’s in charge of the undercover squad. For him, the scales of justice hang low: “There’s more guys out there impersonating cops than there are actual cops.” Despite his beaten-dog demeanor, there’s something paternal about Sorvino and his tender endeavour to introduce Pacino’s Steve Burns/“John Forbes” to the lifestyle he needs him to penetrate, even as he asks the rookie if he’s ever been porked, or had a man smoke his pole. Pacino laughs nervously at the possibilities while we laugh nervously at his perm. Is Pacino meant to impersonate a victim? Or a killer? Does he even get the killer at the end? Is he the killer? And doesn’t Karen Allen, Pacino’s placid-surfaced girlfriend, look fetching in mirrored aviators, studded leather jacket, and peaked Muir cap?

The delightful The Boys in the Band (1970) was a deeply sour and sucked-inside-out musical about bitching and mincing and self-loathing the night away, with Leonard Frey’s “pock-marked Jew fairy,” Harold, one of the screen’s greatest creations. It only managed to offend about half of its target audience. Cruising was hated by almost everyone: “the gay community,” mainstream movie critics, Al Pacino. Endlessly quotable, endlessly interpretable, the movie is a masterpiece, far more subversive and self-assured than any Hollywood film of its decade. (Trending at the time of Friedkin’s death: a video clip of the director announcing, “I do not give a flying fuck into a rolling doughnut about what Al Pacino thinks.”)

Never mind Golden Hour, that favourite of cinematographers and their aficionados, the fleeting, radiant passage from afternoon into evening when the world exudes its quintessential glow: To Live and Die in L.A. is shot (by Robby Müller) mostly in the hours well before the green ray’s glimmer, while the sun’s still hot enough to melt that gold and reveal the city’s shrieking, soot-smeared skull beneath. The film is a bullet directly between the eyes of 1985, when Hollywood studio films were only venturing as close to the edge as Back to the Future and The Breakfast Club. Designed to dazzle though its heart is as cold as the desert at night, To Live and Die in L.A. kicks the post-punk, postmodern, putrid-fuchsia of mid-decade Los Angeles hard in the balls. A pigeon-toed, psycho Secret Service bro named Chance (William Petersen) is determined to bring down a Melrose Avenue–attired counterfeiter and anal-psychotic artist named Masters (Willem Dafoe.) Everyone gets fucked and fucked over. A young and bristling John Turturro (Friedkin liked his “Peter Lorre quality”) swills Pepto-Bismol, Aladdin Sane refugees from Liquid Sky (1982) dance and get naked, and Dafoe wears fire like greasepaint on a face that’s already a Kabuki mask. Friedkin tossed in some Matisse, a cameo for Touch of Evil’s Valentin de Vargas, and slathered the whole thing in Wang Chung—California fusion with a side of freeway mayhem and a shotgun blast to the face—none of that ambiguous French Connection existentialism. Here, the mysteries are Cruising-tested and designed to confront. “Is this my package?” one nutcase asks another as he gropes him in tight close-up. And has there ever been a cheat-cut as intentionally obvious, as audacious or insouciant as the one that Friedkin—who claimed to have made the film in “the unisex style of Los Angeles in the 1980s”—tosses in our laps when he swaps the gender of Dafoe’s performance-artist partner mid-kiss?

Beyond good or bad taste, Friedkin’s city symphony adores everything about its environs, and isn’t afraid to get off the freeway between downtown and LAX to explore surface streets. An anthem to infernal sprawl, To Live and Die in L.A. is a goldmine for admirers of vanished Los Angeles (and Long Beach) locales, offering tantalizing glimpses of the old hillsides around the Tony Scott Memorial Bridge (still officially known as the Vincent Thomas), the wooden Cornfield Yard Footbridge (memorably in This Gun for Hire [1942]), and down beneath the old Sixth Street Bridge by the train tracks, just above the L.A. River bed where Lee Marvin had a similarly frustrating encounter with a briefcase that wasn’t full of money in Point Blank (1967). There’s no escaping the movies here, so in Friedkin’s counterfeiter’s Los Angeles everyone stays true to themselves by being someone else, and every artist’s dream is to immolate their own work, just to see how hot they look in the glow. Central to the film’s margins, John Pankow plays secondario John Vukovich, as blank a cop slate as anyone could imagine: a John is a John is a John. He emblematizes the film, a genre cipher who slips on Friedkin’s own trademark aviator shades—as so many in his films have done—and becomes another perfect black hole at the centre of the filmmaker’s universe. Friedkin claimed he slipped a few of the film’s phony twenties into his wallet before they wrapped the shoot, and later successfully spent them in restaurants around Bel Air.

Has there ever been an example of “late style” as finger-lickin’ good as Friedkin’s Killer Joe (2011)? Along with the tweaker kammerspiel Bug (2006), Killer Joe is one of a pair of compellingly lurid interpretations of Tracy Letts’ plays that Friedkin filmed this century. Expertly shot and edited, it opens with a barking hellhound in the rain, a face full of Gina Gershon’s beaver, and an intimation of Elia Kazan’s Baby Doll (1956). Set amidst some of the grottiest-imaginable trailer trash, the film’s a kind of post–erotic thriller, flying on the twin engines of Juno Temple’s “sleep-talking,” over-ripe nubile Dottie (who is), and Matthew McConaughey’s eponymous death-sorcerer, who’s part true detective, part Terence Stamp in Teorema (1968). A specialist in all-purpose fuckings-over, Joe takes Dottie as a “retainer” for executing his role in her brother’s plan to kill their mother. Lean and leathered-up, Joe could give the killers in Cruising a bruising, and it’s entirely possible to envision the cowboy hat that Pacino threw out the window in the earlier film landing directly on McConaughey’s head: a big naked policeman in a black Stetson, popping in to slap the shit out of everyone. “Whose dick is it?” Joe wants to know. Light meat or dark?

Friedkin takes the stage origins of the material at face value, and revels in it—among many other qualities, Killer Joe reaffirms the director’s skill at photographing hot boxes (The Birthday Party, 1968; The Boys in the Band) and brilliantly opening them out. Set in Dallas but shot outside New Orleans, Killer Joe has a plot, something about an insurance policy and a contract killing and some serious mother issues, but who cares? The whole thing is a pretext for Temple’s awkwardly post-pubescent slinking, McConaughey’s big-dick menace, and one very special family dinner that might have been written by Tennessee Williams…if he’d been bitten by whatever it is that’s bugging Michael Shannon in Bug. Cinema has had its share of chicken-fuckers (think Crackers in Pink Flamingos [1972]), but the screen could scarcely prepare itself for a mascara-and-blood-smeared Gina Gershon, down on her knees, her lips wrapped around a leg of “K-Fry-C,” slowly sucking it while McConaughey keeps her in the rhythm: Kansas City, here I come! As ero-guro as one of Yoshitoshi’s ukiyo-e scenes of sexualized savagery, Killer Joe is dread-and-ambiguity Friedkin at his best. Ultra-vivid though the film is, it ends without ending, still climaxing, and two characters central to the movie’s plot (a guy named Rex and the murdered mom) are barely glimpsed onscreen at all, even though one of them is the two-timer who sets the whole shebang in motion. Never mind the centre: no one colours in the margins like Hurricane Billy. All those casual cutaways to monster trucks on peripheral televisions in Killer Joe? The sorcery never ended.

Friedkin’s passion for “refining” his bullshit continued through the later years and right up to the end. His love for tinkering and tampering with his films in their various digital releases seemed perverse at best: tweaking colour values in The French Connection and others, uselessly obviating minor bits of Cruising, wholly restructuring aspects of The Exorcist with restored footage he’d previously deemed unnecessary and over-the-top. He possibly even okayed a language edit in one streaming edition of The French Connection which moronically seeks to “soften” the rabid racist verisimilitude of Hackman’s “Popeye” Doyle, the specific attribute that the director had once fought so hard (against Hackman’s protestations) to keep in the film. All that beautiful bullshit was bound to draw flies in the end. Finally, age addles us all, and only these glorious fucking movies remain.

Chuck Stephens