Canadiana | A Cinema of Care: The Films of Janis Cole and Holly Dale

By Cayley James

When people discuss the documentary work of Janis Cole and Holly Dale, a number of adjectives will inevitably appear: “caring,” “generous,” and “empathetic,” among them. The filmmakers’ commitment and intention of sharing space with their subjects resulted in what the critic Jon Davies once described as “profoundly ethical and anti-moralistic” filmmaking. This approach is clearly evident in P4W: Prison for Women (1981), Hookers on Davie (1984),and Calling the Shots (1988), three essential films from the duo that received retrospective screenings at this year’s Hot Docs as part of the festival’s REDUX program, which aims to spotlight Canadian documentary filmmakers whose work has been relegated to the outskirts of the accepted national canon.

The festival’s tribute to Cole and Dale was all the more welcome given that their work has at times been left out of discussions of the Toronto New Wave of the ’1980s, even as that decade saw them achieve significant success: they were nominated three times for Best Theatrical Documentary at the Genie Awards (now the Canadian Screen Awards) and took home the trophy for P4W: Prison for Women P4W at the 1982 ceremony. The digital restorations that were shown at Hot Docs are part of a wider project, funded by Telefilm Canada and working in collaboration with Canadian film festivals,, to bring seminal works of Canadian cinema up to current industry standards to. aAllowwing for a new run of theatrical screenings and streaming opportunities.

Cole and Dale met as self-described “street kids,” and by the mid-’70s they were studying filmmaking at Sheridan College, in the Toronto suburb of Oakville. It was here they made their first collaborations—Cream Soda (1975), a study of sex workers at a body-rub parlour on Yonge Street and Minimum Cover No Charge (1976), a profile of their community in Toronto’s Gay Village.Their third film, Thin Line (1977), focused on the inmates of what was then known as the Penetanguishene maximum security hospital for the criminally insane. Cole and Dale have frequently cited their Sheridan instructor, Rick Hancox—now a professor at Concordia University and a seminal figure in Canadian experimental documentary—as a key influence in the development of their filmmaking practice. Encouraging his students to shoot what they knew, he helped open the door for the two to see their own friends and acquaintances as main characters of stories worth sharing.

The visual language of their early 16mm work is athletic and rhythmic, often leading their films to be labelled as cinéema véerité. The duo have bristled at that classification, however, preferring instead to position their films within the lineage of direct cinema, as pioneered in Canada by Michel Brault and Gilles Groulx: “Iit is mixing the approach of cinéma vérité cinema verité and interview so that we can go further than just observing,” as they explained it. This is achieved by exhaustive research, lengthy preparation, and extensive relationship-building, all leading to interviews with a select group of subjects. The editing process reveals a narrative which ebbs and flows from broad scene-setting to narrower—and darker and thornier—issues that subvert audience expectations. There is little contextualizing, no narration, and very little input from so-called “experts” on the subjects being explored. Their approach has become, not quite commonplace, but definitely embraced by non-fiction storytellers from across the documentary spectrum. You can see similarities in films by filmmakersmakers of their own generation including Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning ([1990)] or Kim Longinotto’s incisive character studies (Sisters in Law, [2005]), .a As well as in newer more fluid non-fiction forms like the cultural anthropology of Brett Story (The Hottest August, [2019])or the impressionistic work of RaMell Ross (Hale County This Morning This Evening,[2018]).

Cole and Dale’s first feature, P4W: Prison for Women (1981), was made for just $32,000 and filmed in 18 days, with a skeleton crew consisting only of the directors, their sound recordist, and a cinematographer. Upon its release it became one of the most successful documentaries ever made in Canada, grossing a quarter-million dollars in domestic sales. At the time, the Prison for Women in Kingston held a population of approximately 100 prisoners and was the only federal prison in the country for female convicts. It took five years for the filmmakers to be granted access to film inside the prison, and they were forced to abandon their original intention to stay in the prisonovernight during the shoot when the warden limited their access to between 7am and 9pm. According to Dale, “There were about 60 women who wanted to be in the film, and we narrowed the list to half a dozen people that we really wanted to focus on. The women [Bev, Janise, Debbie, Maggie, Susie, June] made the nucleus of the film, representing the prison, prison society, and the inmates.” The camera zips around the prison, intercutting between talking-head interviews woven in with fly-on-the-wall footage of everyday life in the prison. The interviews are intimate, marked by humour and honesty. Onscreen, the women exhibit a palpable respect and attentiveness at not only having a chance to speak but to be listened to as well. The camera is trained on their faces, usually in tight close-ups or medium shots, and quite often they look straight into the lens rather than in the direction of the interviewer, pulling the audience into their world.

Although fluid, the film’s structure ultimately leads toward a damning conclusion that calls into question the integrity of the Canadian criminal justice system and hones in on the ever-present spectre of violence and neglect. Multiple subjects testify to the negligence that had lead to deaths in the prison. In one incredible exchange, an older inmate trying to advocate for the rights of the population is dealing with “Claire,” an administrator who looks all of 20 years old: “Why do I have to have three slashings and a stabbing in one day before someone sits up and say, ‘Hey, something is happening here! That’s not right…When a person is doin’ that, they’re just asking for help!”

Cole and Dale’s experience on P4W continued to inform both their politics—Holly joined a group called “J‘Justice for Janise”’ to lobby for one of their subjects to receive a clemency trial after the film was released—and their filmmaking,. gGoing on to make a Heritage Minute about the 1920s Prison reformer Agnes McPhail in 1992. While Oon a more personal note, during the making of P4W, the directors had forged a friendship with one of the inmates, Marlene Moore a.k.a. Shaggie, who subsequently committed suicide while still incarcerated. In the aftermath of Shaggie’s death, they paid tribute to her in two projects: first in the Cole solo-project Shaggie: Letters from Prison (1990), a short memorial that weaves together voiceover readings of letters with re-recorded footage from P4W and stylized sequences; and the docudrama Dangerous Offender: The Marlene Moore Story (1996), which dramatized Shaggie’s life for a national television audience which Cole penned and Dale directed for CBC.

Their handling of sensitive issues was, for the time, novel, and the films’ broader cultural critiques were perhaps too easy to miss or to dismiss. In an essay in Cinema Canada from 1978, critic George Csaba Koller noted: “The films of Holly Dale and Janis Cole so far all deal with some form of social deviance, either every queen, dyke and hooker on the corner, and some psychopathic killer thrown in as icing on the cinematic cake.” But as Dale explained, in conversation with critic Matthew Hays in his book The View From Here: “We were unconsciously making films that were trying to remove labels from people, which later became a very conscious thing for us when we starteding doing P4W and Hookers on Davie.” The latter is notable for standing in stark contrast to the anti-porn/anti-sex-work position that dominated the discourse of many Western feminists at the time. The film had initially taken shape thanks to funds from Studio D, the groundbreaking feminist film unit within the NFB, butthe relationship broke down. Studio D requested final cut, wanting something simpler than an honest portrayal of sex work, populated by people who find acceptance and a community on the street. The NFB had made a splash in 1981 with the second-wave feminist documentary, Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography, which featured interviews with leading feminists of the day including Margaret Atwood and Kate Millet and explored the abuses of the adult entertainment world. Having made this film—timely and important in its own right— with a moralizing lens, perhaps the institution did not want to wade into the Cole and Dale’s complicated reality. As Dale differentiated in 1984, “The Board’s [NFB] style is to believe that people want you to make up their minds for them— – and maybe some people do—but we like to think our audience is more intelligent than that.”

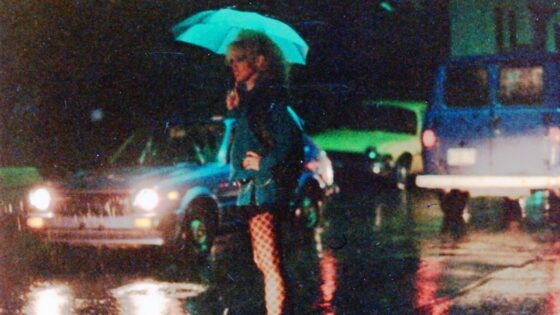

Just as P4W exposes the intolerant, apathetic heart of a bureaucratic system, Hookers on Davie explores how society both misunderstands prostitution and shames prostitutes. The opening minutes of the filmimmediately immerses the audience in the world of Vancouver sex workers with a montage of the Davie neighbourhood set to The Crusaders’ 1979 disco classic “Street Life.” The rapid cuts between the working girls on the corner and the neighbourhood’s older residents emphasize the discordance of a densely populated residential area and bustling commercial corridor with the hustling activities of the prostitutes. The film follows a core cast of characters, varying in age from 19 to 41 and who work the streets without pimps, including Tiggy, Rickie, Joey, Tiffany, Bev, Michelle, and a small group of unnamed others. Much of the footage of the girls working their corners was shot with the aid of hidden remote mics, with the camera crew set up in a van across the street. Cole and Dale don’t shy away from the violence and risk that comes with this line of work, but they nevertheless are able—with banality and humour— to effectively communicate the intimate moments of their subject’s lives. Viewers are privy to the girls’ exasperation with tricks, the inside baseball of negotiation, their jokes, and the intimate moments of their friendship (both good and bad). Stripping prostitution of its salacious allure, and providing essential perspective, they frame it in terms that have now become a common refrain by advocates in the sector: “Ssex work is work.”

It is this compassion and curiosity that anchors their films. In conversation with Matthew Hays, Janis Cole explained; “We didn’t lead our subjects to believe that we were being friendly with them; we actually were friendly with them.” They have spoken openly about maintaining friendships during and after the films wrapped and these relationships allowed them to dig deeper into the lived realities of their subjects. In the case of Hookers on Davie, even something as simple as interviewing the subjects at home or observing their post-work drinks lends them the literal space to not define their subjects exclusively by their work.

There is an interview, about halfway through Hookers on Davie, that exemplifies this care. We move off the street and see one of the film’s main subjects, transgendered Michelle, collecting her mom at the airport. The image of a put-together, middle-aged women with set hair and a smart day dress and trench coast stands in stark contrast to the big hair and glamour of the working girls. But she has her own world weariness, distinct from the one felt by the girls who pepper their serious truths with sarcasm and joking asides. Cole and Dale capture her sorting through her feelings in real time in Michelle’s cozy apartment, surrounded by houseplants. “So where do they go? What do they do? No one has been able to answer me.” She pauses, sighs, and explains that people will say that she’ll “probably just find them dead in a gutter one day,” referring to Michelle. The camera holds on her face, one tired from worry but seemingly resigned to a society where the humanity of her child isn’t worth valuing.

Survival in the face of great odds is the through line that connects all of Cole and Dale’s work. Their third feature, Calling the Shots (1988)—a wide-ranging survey of women filmmakers in the ’1980s—seems at first glance like a significant departure for the duo, but although their environs have changed from prisons and street corners to film sets and production meetings, the Sisyphean struggle remains. Featuring richly detailed and emotional interviews with the likes of Joan Tewkesbury, Joan Micklin Silver, Penelope Spheeris, Jeanne Moreau, Agnèes Varda, Susan Seidlelman, Lizzie Borden, and many, many more, the film covers a wide array of topics, including the misogyny of the film industry, the difficulties of raising money, and the realities of sustaining a career. Despite its breadth, it still burrows deep.

What Cole and Dale sacrifice with Calling the Shots’ wider scope and larger group of subjects is the visual energy of their previous films, its roaming camera immersing itself into situations. The only times the film breaks from the talking heads are for photos, brief montages of Los L.Angeles., film clips, and two very welcome sojourns to film sets being overseen by Sandy Wilson and Martha Coolidge. Calling the Shots’ individual interviews are a telling visual representation for what it is like to be a woman filmmaker working in mainstream cinema— there are few women seen working or interviewed together. Rather, when people are brought up, or stories involve multiple interview subjects, there is a pinball effect, bouncing from one account to another, teasing out the situation fragment by fragment. This approach is not radically different from how Cole and Dale have composed their previous projects, but without the immersion in a physical community, its isolation is more pronounced.

Calling the Shots is a poignant touchstone, marking the end of the second era in the creative partnership of Janis Cole and Holly Dale. In the ’‘90s their creative interests drew them in different directions: Janis towards writing, teaching and experimental film, while Holly began working steadily directing television. The restoration of their films will bring new—and renewed—attention to a 20twenty-year collaboration that was typified by nuance, by a refusal to cater to convention, and by an insistence on providing a platform for people to speak their truth.

P4W, Hookers on Davie and Calling the Shots are available through Films We Like.

Cayley James