Home Sweet Homeless: The Harmonious Dissonance of Otar Iosseliani

By Celluloid Liberation Front

“Censorship in the west is like everywhere else, it forces my colleagues to follow certain rules—the first rule being the box office.”—Otar Iosseliani

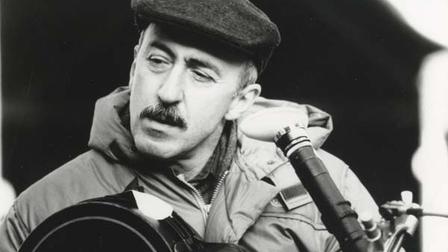

Almost unnoticed, bucolically roaming the canting bustle that is the film industry, where smiles range from vile to servile and vainglory is king, the cinema of Otar Iosseliani has stared amusedly at this pathetic travesty for over fifty years. Within this pitiful scenario, where imagination is degraded and arrogance ennobled, Iosseliani has cultivated an indolent and melancholic cinema that lingers on small details to reveal the wonder and absurdity of life. Storylines are evanescent pretexts, narrative excuses to explore the ethical and aesthetic implications of paradoxes. Whether it is a young musician in Soviet Georgia repeatedly not turning up at orchestra rehearsal or a politician in Paris rediscovering the humble joys of daily life after years locked away in the cage of democracy, Iosseliani’s films favour diversions. His oeuvre may not always be easily likable but it is hypnotic and absorbing, contemplatively pausing in front of the modest and seemingly irrelevant aspects of human life (often measured against the astonished indifference of animal life). Iosseliani’s enlightened detachment avoids declamations to pursue the instincts of a vision, without ever trying to impress a vain authorial signature upon his films. Iosseliani, if anything, is a sab-auteur, undermining the presumptions of art cinema to reaffirm the vanishing wisdom of craftsmanship.

The rootless cultural matrix of Iosseliani’s cinema, where a glass of wine is as noble as a painting, is simultaneously palpable and unfathomable, neither Georgian nor French, epic like an aimless dalliance. A transitory feeling traverses all his films, as if nothing could ever happen for the first or last time. The protagonists of Iosseliani’s films, caught in an ironic dream state of cinematic indeterminacy, mind their own business and ignore the audience’s anxious expectations. Instead of offering an interpretation, a guide or an (ideo)logical key, the director return his actors’ gaze, staring back at them with penetrating indolence. Iosseliani discloses the submerged essence of expression within the frame, which so much cinema often blacks out in its frantic effort to give meaning to that which is meaningless. His films gather coincidences rather than orchestrating consequential narratives; different stories pass through the frame, leaving the impression of a ceaseless continuing elsewhere. As in life, nothing is fully accomplished; everything is impeccably imperfect. An unfashionable kind of elegance characterizes all of his films, a sort of aristocratic formalism: the aristocracy of the dispossessed.

Born in Tblisi, Georgia in 1934, Otar Iosseliani studied music at the Tblisi conservatory from 1944 to 1953, graduating in piano, composition and orchestra lead. From 1953 to 1955, he studied math at the University of Moscow before studying directing at the pan-Soviet film school VGIK at a time when the early masters of Soviet cinema were sent there to teach, as their work did not fit the mould of Stalinist socialist realism and was therefore unsuitable for propaganda. Among Iosseliani’s teachers were Alexander Dovzhenko, Mikheil Chiaureli, Lev Kuleshov, Mikhail Romm, and Grigori Kozintsev. After having diligently and enthusiastically served the revolutionary cause, all of these artists had started to become aware of the unimaginative nightmare the Soviet Union had turned into; and so, according to Iosseliani, the state film school ironically began to form future dissidents, as these ex-revolutionaries began to pass their disillusionment on to the next generation.

After completing two student shorts—Akvarel (1958), an irreverent exercise in socialist surrealism, and Song About a Flower (1959), a vernacular symphony of floral dynamism and stubborn resolve—Iosseliani graduated in 1961. His first professional short, April (1962), a tale of denied intimacy, was immediately censored—according to Iosseliani, because “it’s a fairy tale, and fairy tales are extremely dangerous for totalitarian systems […] it’s the eternal struggle between artists and the powers that be, it didn’t only happen under Hitler or Stalin.” Iosseliani temporarily abandoned cinema, working first on a fishing boat first and then a metallurgical factory; the latter experience would be captured in Tudzhi (1964), a short documentary that marked Iosseliani’s return behind the camera. His first feature, Falling Leaves, was presented at the Cannes Critics Week in 1967, where it won the FIPRESCI prize. The story of two young friends working in a wine cooperative—the one honest and idealistic, the other petty and self-serving—the film is less an allegorical parable than a look at the petty miseries and artless delights of communal life and work. Similarly, while the film world was busy fighting against “le cinéma de papa,” with Georgian Ancient Songs (1968), Iosseliani composed a tiny, melodious short which is also a plea for the preservation of an ancient tradition then threatened by an overbearing Soviet presence.

In 1971 Iossliani made his international breakthrough with There Once Was a Singing Blackbird. Ghia, a young timpanist at the Tblisi opera theatre, seems preoccupied with everything else except his place in the orchestra, which he nonetheless honours with (im)perfect timing, always turning up at the last minute. Constantly reprimanded, Ghia keeps missing appointments while drifting with eager abandonment across the city, forever lured by sparks but oblivious to the fires they might start. He starts to court a girl but fails to turn up for their date; after a series of liberating if inadvertent derelictions, he gets run over by a truck, so that the universal clock can keep tick-tocking without further disruption.

To this day Iosseliani’s career is characterized by generous intervals, as if life and inactivity were as important to tend to as work. Five years passed after his critical success with Blackbird before his follow-up Pastorale (1976), an ode to the fruitful dissonance of urban life meeting the rhythms of rural life. A group of musicians moves to the countryside from the city looking for a quiet place to rehearse. There they encounter, are seduced by and eventually depart from a different universe, leaving behind but a faint trace of their passage. In 1979, Iosseliani moved to France, where he made two shorts. Sept piéces pour cinéma noir et blanc (1982) is an audio-visual counterpoint that orchestrates glimpses of Parisian life into a joyful cacophony. Removed from its inherent political dimension, Euzkadi eté 1982 (1983) documents the festive mood of the eponymous Basque country town, its interpretation of life and art conveying a profound sense of cultural autonomy. In 1984, Les favoris de la lune (its title referring to Shakespeare’s definition of thieves, “moon’s favourites”), Iosseliani’s first feature-length film since moving to France, won the jury prize at the Venice Film Festival. The Parisian anthill teems with ordinary extravagance, with characters bumping into each other in the frantic construction and destruction that is urban life. It’s a chorus of unpredictable actions whose mutual incompatibility somehow constitutes the very (dis)harmony of city-dwelling that Iosseliani observes amusedly, noticing what usually goes unnoticed. Multiple characters chase after a fleeting happiness, which keeps eluding them, sentencing them to a perpetual sate of aimless search. The film posits itself at the centre of this spinning madness while simultaneously framing it from the outside, both participating and detached, anxious and amused.

Four years of silence and life were followed by Un petit monastére en Toscane (1988), where Iosseliani hooks up with a cheerful bunch of monks in Tuscany and shares with them the pleasures of wine and good cuisine. Hunting, singing and the rituals of monastic life open themselves to the camera and to mutual contamination. His next film, Et la lumiére fut (1989), probably counts as the sole instance of a white filmmaker filming Africa and its inhabitants with neither liberal-progressive guilt, anthropologic pretension, or emancipatory aspirations. A beautiful woman getting tired of her lazy husband, a group of idiotic defoliators coming to the village, empty wells that get magically filled with water, and the arcane rites “civilization” can do without are the tangential protagonists of this unassuming story. It’s Africa, but Iosseliani films it as if it were a Parisian neighbourhood, a picturesque spot of the Georgian capital or a monastery: a place inhabited by people busy dealing with the convoluted simplicities of life.

After La chasse aux papillons (1992) and Seule, Géorgie (1994), a documentary about the history and culture of his native land, Iosseliani returned to Georgia to make Brigands Chapitre VII (1996). Back in France, in Farewell, Home Sweet Home (1999) Iosseliani serves up extravagant sketches of Parisian life, capturing the anonymous and discreet beauty of a city that countless directors have crudely worshipped but never observed. The son of an aristocratic family works as a dishwasher while his mother performs with herons in front of distinguished guests and conducts business from a helicopter. The father spends his merry days drinking alone in his room, until one day his son brings home a cheerful bunch of drunken drifters with whom he will immediately strike up a heartfelt friendship. The ostensible serenity conceals a calm neurosis; with elegant aplomb, the unresolved vexations of daily urban life are brought to the surface, not to resolve them but to look at them for what they are, escapable contingencies.

While most of Iosseliani’s cinema has been concerned with the static nature of ordinary movements and routines, Monday Morning (2002) is a pleasant detour that follows a middle-aged family man who, in order to be closer to his family, leaves it behind. Iosseliani’s films his protagonist’s trip to Venice as if through the character’s own eyes, sharing with him his longing for a different landscape. Once again Iosseliani manages to film a city vulgarized by too many postcards from a magical, nameless perspective where every occurrence exudes wonder and every encounter is revelatory. Regenerated by his journey, the father will return to his home and family: his son spots him while hand-gliding over their family turf, a Rhône valley inhabited by crocodiles. From the French countryside back to Paris in Jardins en automne (2006), the government’s Minister of Agriculture loses his job and has to go back to a terrestrial reality, one he initially struggles with but eventually finds far more fulfilling than his previous career; now in his fifties, he is finally free to hang out with friends and old lovers, and start a new life far from the regal constraints of institutional politics. Like a garden blossoming in autumn, the protagonist finds a new reason to live late in his life, enjoys once again the company of his old mother (a great performance from Michel Piccoli), and dedicate his time to flowers, wine and friends.

Iosseliani’s latest film, Chantrapa (2010), is a parodic, autobiographical take on the hardships of making films under censorial restraints, in Soviet Georgia as well as in democratic France. A young filmmaker struggles to have his film made, first in his native Georgia and then in France, where he migrates in the hopes of greater artistic freedom. After many hilarious vicissitudes, where censorship appears as both comical and obtuse, the young filmmaker will finally have his film premiered; only one elderly spectator (played by Iosseliani himself) and his beautiful wife will stay to the end.

“When a film is successful, I think, it’s always a bad sign,” Iosseliani ponders. “As far as I’m concerned to make ‘great cinema’ is absolutely impossible, the very idea repels me. These are my criteria, there is nothing I can do about it.” For perhaps nothing can be done about many things except comprehending the charming insanity of human life on earth in all its meaningless beauty. The meditative irony of Iosseliani’s cinema stands out for its unexpected angle that somehow manages to show a familiar thing in a completely different light. The surreal animal presences that populate many of his movies seem to suggest the awe and shock with which animals must look at us, a perspective that Iosseliani’s look whimsically conveys. As modern life accelerates beyond any limit, depriving life of the time it requires, Iosseliani’s cinema is a timely reminder of how vital idleness is. He is, after all, a director who films the ineluctable fate of objects and wo/men in all its absurd, painful and ridiculous magnificence while trying to salvage the time we don’t seem to have, let alone master. An inconspicuous, charming anti-conformist whose simple and profound cinema feels more like friendships than films, evoking the fading art and pleasure of conviviality.

Celluloid Liberation Front