Agrarian Dystopia: David Wain’s Wanderlust

By Adam Nayman

One of the great joys of David Wain’s Role Models (2008) was the way that it satirized live-action-role-playing culture while also conceding the appeal—and even exhilaration—of attaining one’s second-life goals. When Augie Farcques (Christopher Mintz-Plasse) finally topples the arrogant weekend-warrior monarch of L.A.I.R.E. (which stands for “Live-Action Interactive Role-Playing Explorers”) it’s not just the payoff to a jokey subplot about nerds with Nerf swords. It’s the culmination of a quietly audacious narrative strategy whereby a collection of fuck-ups redeem their real-world failures by pledging allegiance to an ersatz medieval realm. Role Models ends almost immediately after the conclusion of the L.A.I.R.E. battle royale because its principals have finally found the continuity of community. There’s no need to show them settled back in their “real” lives, because the characters and audience alike are wholly committed to this shabby simulacrum of serfdom.

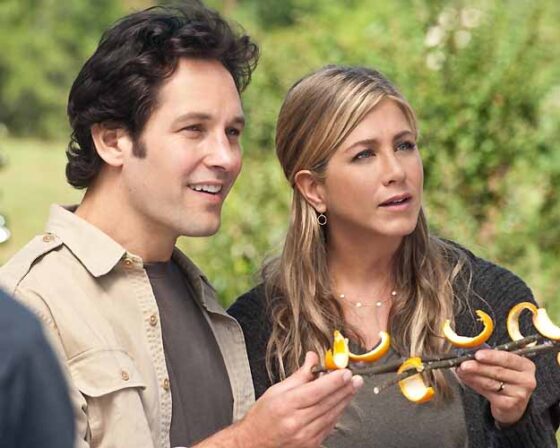

George (Paul Rudd) and Linda (Jennifer Aniston), the married protagonists of Wain’s new Wanderlust, are in a sense role-playing explorers themselves. No less than David Twohy’s A Perfect Getaway (2008), Wanderlust is a comedy of identity-(s)hopping, centred on a couple so perpetually uncomfortable in their own skins as to make shedding them a habit. They’re not sociopaths like A Perfect Getaway’s thrill-killing ciphers, and Wanderlust doesn’t go nearly as far as Twohy’s masterpiece in considering and critiquing the pathology behind trying on new lifestyle options like they were choices from a high-end clothing catalogue. But Wain and his eternal co-writer Ken Marino still do more with their yuppies-go-off-the-grid scenario than any filmmaker since Albert Brooks. Chased out of New York by professional setbacks and a collapsing housing market that renders their “micro-loft” instantaneously worthless, George and Linda become initiates at Elysium, a rural Georgian commune governed by the tenets of free love and shared possessions; if the place has a motto, it’s founder Carvin’s (Alan Alda) mantra that “money buys nothing.”

“Actually, money buys most things,” stammers George in retort—the perfect Ruddian response. Since being reborn as a charter member of the Apatow brand (which has put its imprimatur on Wanderlust), Rudd has made a comic specialty out of being the smarmy literalist who can’t quite go with the flow, his aggrieved rant to a coffee-house barista about the true meaning of the word “venti” in Role Models being a kind of signature scene. (The exception: Jesse Peretz’s amiable but middling Our Idiot Brother [2011], where Rudd’s Lebowski-lite character seemed to be auditioning to be a background player at Elysium.) Rudd’s skill at playing clenched characters belies his generosity as an actor, and he seems to energize Aniston, who is more comically liberated here than in the horrible Horrible Bosses (2011), even if one can’t help but imagine a real dynamo like Elizabeth Banks in the part.

There is, surely, a mechanical aspect to the way that George, initially so receptive to his new surroundings, becomes skeptical at precisely the moment that Linda throws herself body and soul into the flower-child shtick. But there’s also something wise in how Rudd and Wain locate and kid the precise nature of his disappointment. George’s sojourn in Elysium has less to do with reclaimed counterculture ideals than the convenient illusion of distance from a material world he hasn’t given up on. Persuaded by in-house guru Seth (Justin Theroux) to purge his rage at the world through loose-limbed modern dance moves, George swings his arms mightily but the first grievance he can muster is against nothing more malevolent than mushrooms: “I don’t like their texture.”

Rudd’s greatest scene—the one that has already been cited by other critics and seems destined to be a YouTube favourite—finds George the hypothetical hippie trying to persuade himself towards praxis. Given the green light to hook up with blonde goddess Eva (a fetchingly feline Malin Akerman), he gets in front of a bathroom mirror for a self-motivational monologue that descends into demented hillbilly accents and tortured facial contortions worthy of Peter Sellers. Shades, perhaps, of Owen Wilson’s reticence in Hall Pass (2011), and George’s inability to ultimately do the deed with Eva could be read as evidence of an underlying conservative streak. Ditto for the way that Linda’s own, consummated act of indiscretion occurs offscreen in a film with plenty of lasciviously rendered sexual situations. Maybe it’s more fair to say that this hangdog restraint is indicative of a conflicted moment in American movie comedy.

In nearly every other important way, Wanderlust distances itself from the pack, its privileging of ensemble dynamics place it closer to Wain’s sketch-comedy roots than the above-the-title mugging of most Apatow joints (and there is a welcome, Stella-esque bit with Wain, Michael Showalter and Michael Ian Black as cable-affiliate newscasters bullying their long-suffering female colleague). Elysium’s sprawling country-house-without-doors is not only a metaphor for George’s assaulted sense of privacy but a fertile space for a troupe of performers whose verbal and physical interactions are so tight as to give the impression of a single, pachouli-scented organism. Theroux’s maniacal swami is a superb comic creation (he makes the pronunciation of “Miami” an event), but he’s made even better by the way that Michaela Watkins and Kathryn Hahn, playing longtime acolytes, hang bedroom-eyed on his every word (they’d be great in a full-dress parody of Martha Marcy May Marlene [2011]).

Wain has inevitably improved as a technical filmmaker since his cult flop Wet Hot American Summer (2001), the sloppiest yet most crystalline feature-length expression of his half-benign, half-contemptuous comic sensibility. He’s now confident enough to stage surreal visual gags (like a symbolically loaded dream sequence involving a talking fly) and uses editing for effects rather than just a way in and out of scenes. A stop-start montage of George and Linda bickering during their cross-country odyssey is perfectly rhythmed between the actors and the music on the radio and also serves as a sweet shorthand depiction of the tetchy combat tactics of loving long-term relationships. The interludes at the Atlanta McMansion of George’s abusive brother Rick (a priceless Marino) are far more ambivalent about suburban luxe than the comparable sequences in Apatow’s Funny People (2009). Even the transitional soundtrack music is thoughtful: the use of R.E.M.’s “Driver 8” from back in their “subculture-galvanizing days” (as per Gina Arnold) is both regionally appropriate and, tied to George and Linda’s journey from Elysium to Atlanta, slyly suggestive of the band’s journey from the margins to the mainstream.

Wain’s own crossover move, meanwhile, is complete, and while there will probably be longtime fans who resent seeing such an outside-the-box comedian migrate to the multiplex, they can take solace in the fact that it’s less a case of a filmmaker selling out than the industry playing catch-up. Reviewing Wet Hot American Summer back in 2001, Michael Atkinson aptly observed that [“the film] will be loathed, but it might be ahead of its time,” and it’s not hard to perceive the trickle-down effects of its thrillingly loose, purposefully unpolished style on a lot of the key American comedy that followed, from the pop-inflected non-sequiturs of Adult Swim programming to the dead-air ethos of every other premium-cable sitcom (especially Party Down) to the thriving alt-podcast community (in which Wain’s own Wainy Days YouTube series is a sort of satellite phenomenon).

There’s too much studio money behind Wanderlust for it to commit fully to an anarchic mode, and the ending, which suggests the discovery of a happy medium between bourgeois and bohemian modes (as subsidized by an unexpected literary windfall), is predictable and compromised. But, like the film’s previous depictions of capitalist entrapment and agrarian dystopia, the loose-end tying is so jovially exaggerated as to short-circuit any sort of serious reckoning with the film’s “message.” All Wain is arguing, in the end, is that sometimes it’s nice to have doors around. If that’s a more closed-off attitude than the fantasy/reality slippage at the end of Role Models, it’s also still squarely within the comedy-of-remarriage tradition that acts as a road map for a director still gamely chasing his whims.

Adam Nayman