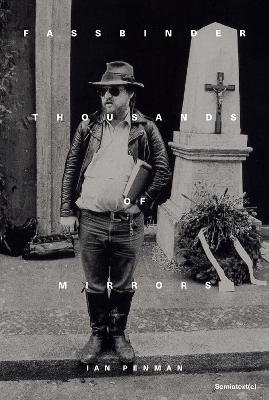

The Self in Shards: Ian Penman’s Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors

By Erika Balsom

“The night he died I was in a north London nightclub, where I took heroin for the first time. I returned to my south London flat the next morning, threw up, and went straight in to work, where someone immediately told me about his death.” This fragment, the 421st of the 450 that comprise Ian Penman’s engaging new book Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors, strikes me as something much more than a “where were you when…” sort of anecdote. It cuts to the core. Arriving late in the game with a stinging force, it sutures together two unrelated events in 1982: an opioid turn in the writer’s early twenties, and the drugged-out expiration of his subject at age 37. Across the book, Penman leans hard on Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s last days, as if the director’s death and the way of life that led to it exerted an abyssal pull on him. Penman seems driven by a biographical fascination with the decadent intensity of the enfant terrible from Bad Wörishofen—or is it an autobiographical fascination? As Fassbinder winds down, the parallel tracks established from the start—the life of the writer, the life of the filmmaker—collide in an intoxicated night during which one era gives way to another. For the young Penman, Fassbinder was a role model, a “post-punk ideal,” “wildly glamorous and deeply scuzzy”; retrospectively, he appears as a bridge between the revolutionary ’60s and the sick ’80s.

Calling the book Fassbinder makes it sound like a monographic study, when in fact the true nature of the undertaking is better discerned from its subtitle and opening epigraph. Like Fassbinder before him, Penman borrows from Vladimir Nabokov: “For I do not exist: there exist but thousands of mirrors that reflect me. With every acquaintance I make, the population of phantoms reflecting me increases.” In the proliferating mirrors of this compendium of numbered fragments, we surely get glimpses of Fassbinder and his cinema, a cinema in which, to borrow Thomas Elsaesser’s memorable formulation, “to be is to be perceived.” But above all, what comes into view is a portrait of the English author as refracted through the life and death of the German director, and many other continental spectres besides. Janet Malcolm suggests that, “If an autobiography is to be even minimally readable, the autobiographer must step in and subdue memory’s autism, its passion for the tedious.” Penman most definitely steps in, supported by a chorus of phantoms.

Criticism is a parasitical practice—it must feed off a host to come into being. This does not mean it is an impersonal affair. Some leave no trace, but the best critics are always indelibly there, even when they make no mention of their own lives. Penman tips this balance to the far side, taking criticism to the threshold of memoir, drawing in what he needs to go where he wants to go. Rather than working through Fassbinder’s filmography in detail, the book draws on an immense range of cultural references across disciplines to piece together an account of one person’s experience of “back then.” It vibrates with the excitement and seduction of youthful subcultural discovery; it trembles with the queasy sense that a new and different darkness was on the verge of setting in. Penman says that Fassbinder might be his “own equivalent of what Baudelaire was for Walter Benjamin”—an artistic figure from the past, positioned on the cusp of a major epochal shift. What he does not mention is something equally important: as with Benjamin’s Baudelaire, here the artist becomes a medium. Fassbinder is a substance passed through to get somewhere else. He is also a way of summoning ghosts.

Penman is best known as a music critic who began sprinkling references to French theory into NME in 1977. When his first collection, Vital Signs: Music, Movies, and Other Manias, came out in 1998, Iain Sinclair called him “non-eminent (but legendary),” underlining the writer’s antipathy to journalistic convention and sketching his drift away from the establishment, into his “wilderness years.” These days, this anti-hack contributes essays to the London Reviews of Books on figures like Prince and Elvis, and is “the most drug-free [he has] been since the late 1970s,” without even a cigarette in nine months. Illicit substances are not the only things to have a decreased presence in Penman’s life today: the cinema, too, is a relic. If movies ever were his beat, they aren’t anymore. Rather than seeing Veronika Voss (one of his favourites, and mine too) four times in its opening week as he did in 1982, he now binges crime series on Netflix instead, shifting not only exhibition context but preferred content as well.

This is all to say that Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors is in multiple respects written from the other side of a divide, as the author looks back at his own life, at all that he has left behind and is no longer. To recall and revise a notion of Jean-Louis Schefer’s, at issue here are the films that watched over Penman’s young adulthood. Serge Daney unfolds Schefer’s idea with typical brilliance: “It is one thing to learn to watch movies as a ‘professional’—only to verify that movies concern us less and less—but it is another to live with those movies that watched us grow and that have seen us, early hostages of our future biographies, already entangled in the snare of our history.” Penman is a celebrated writer who has sometimes been paid to write about cinema, but he is no professional, has never wanted to be one. He is an autodidact who holds that kind of training in disdain, as something that blunts sensibility. He does not hide his contempt for academics, even as he cites Derrida’s Glas; he remains caught in the idiosyncratic trap of passion, in the snare of his own history.

As a result, a time-capsule feeling takes hold. One casualty of this is that cinema appears as a mummified entity: there is no engagement here with filmmaking as a living tradition, or with any of the directors who might claim to carry forth something of the Fassbinder approach today, whether consciously or not. (To name only a few: Albert Serra, with his chosen family of performers, returning again and again in changing configurations to realize the master’s vision; François Ozon and Todd Haynes, with their queering of melodrama; or even Hong Sangsoo, with his tireless production of “minor” works.) Penman goes so far as to suggest that Fassbinder himself has been somewhat forgotten in our time of streaming content, asking, “Why hasn’t he been curated and archived and appropriated and name-dropped to death?” (My immediate thought: hasn’t he? I suppose it all depends on where one stands.)

But to complain about the lack of a more cine-centric approach here is to miss the point. There are plenty of other writers who immerse themselves in contemporary filmmaking, and plenty of places to go for more conventional accounts of Fassbinder. Gossipy exposé, rigorous historicization, close reading, an account of his legacy and influence—take your pick, they all exist. Penman walks a different path, one that only he could.

To complete Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors, his first original book, Penman mimicked the industriousness of his ostensible subject, writing quickly enough to finish in just over three months. He breaks up his text into numbered entries that are sometimes barely a sentence long, and rarely more than a page. This bricolage includes quotations presented without commentary (from figures such as Jean Genet and Klaus Theweleit, as well as critics on Fassbinder and the director himself); recollections of the author’s life, from childhood on; some rehearsal of RWF lore; zoomed-out commentary on selected films; and various excurses on related issues. Penman prefers to name and cite rather than explain, evincing a special predilection for staccato lists and rapid-fire declarations. The following is not anomalous: “Mood: hard drugs, terror tactics, need-to-know secrecy, the ever-present threat of horrific violence, surveillance tapes, VHS porno, Maoist play acting, and ‘radical’ as a self-righteous identifier of choice.” One entry reads simply, “Gerhard Richter’s 48 Portraits (1971/72).” Interrogative statements pile up. Penman’s telegraphic style is poised somewhere between casual brainstorming and chiselled exactitude, provisional speculation and world-weary assuredness.

The author’s working method might be part of what generated this form, and perhaps also goes somewhat toward explaining the primacy the book accords to atmosphere, its tendency to digress and to traffic in associations, and the absence of in-depth sequence analysis. But this could also just be Penman’s M.O. more generally, indicative of aptitudes honed through his short-form pieces about pop stars and pop music. He has a formidable skill for getting the contours of a larger-than-life persona and the feeling of a zeitgeist down on the page, both of which are more closely associated with music writing than with the textual dissection that grounds most film criticism. If I have made scarce comment thus far on what Penman actually says about Fassbinder or his films, it is because what is most compelling about this book (and it is indeed compelling) are not its precise insights into the director’s oeuvre or persona, many of which are familiar enough—it is the author’s positioning of these within a much wider, unflaggingly personal constellation of obsessions and experiences, all delivered in distinctively styled prose.

If one wanted to rebut Penman’s claim that Fassbinder has both “thank Christ…escaped being turned into a monument” and “been so dishonoured by not being turned into a monument,” one would have to look no further than the immense dossier on the director published in the May 2017 issue of Sight & Sound. RWF is there on the cover, leather-clad, cigarette in hand, on the occasion of a two-month retrospective at the British Film Institute. Funnily enough, the article inside most germane to Penman’s Fassbinder is not any of the many concerning the director of The Third Generation (1979, another one of Penman’s favourites, a poster of which hangs in my office)—rather, it is Adrian Martin’s “What is Literary Cinephilia?” a text charting a wide category characterized by “an equal exchange between literature and cinema,” one vein of which includes titles such as Nathalie Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden and Geoff Dyer’s Zona: A Book about a Film about a Journey to a Room. Here, we move beyond the confines of conventional film criticism into a cluster of genre-bending books written by individuals not primarily associated with cinema, and often with a strong stake in memoir—a bibliography that Fassbinder now joins.

“Literary cinephilia.” Is there another art form for which a comparable critical phenomenon exists? Where so many celebrated tomes, so much of the best writing, comes from people whose real intellectual home (if such a thing can be said to exist) lies elsewhere? Maybe photography. But what does this tell us about film? Perhaps something inspiring. Cinema speaks to us about our lives and our existence; it overflows the silos of expertise to produce sophisticated and compelling responses from non-specialists who unravel its connections to lived experience, politics, culture. It shapes even those who do not organize their lives around it in ways that demand an account; it is, as Daney said, a relation to the world.

But what might the phenomenon tell us about film criticism? Perhaps something not so nice. What gets happily left behind in these books is not only all that “professional” movie-watching—the pedantry and obfuscation of some academic writing, the superficial, PR-beholden banality of much new-release reviewing and festival reporting. They also dispense with the hermetic enclosures that pervade film criticism, even (or especially) in its more serious guises. They break with the pervasive tendency to discuss movies principally in relation to other movies. There are many writers who are incapable of mentally exiting the cinema, even when the air gets impossibly stuffy. That hall of mirrors is one Penman never enters.

Erika Balsom