DVD | Reclaiming the Dream: Joyce Chopra’s Smooth Talk

By Beatrice Loayza

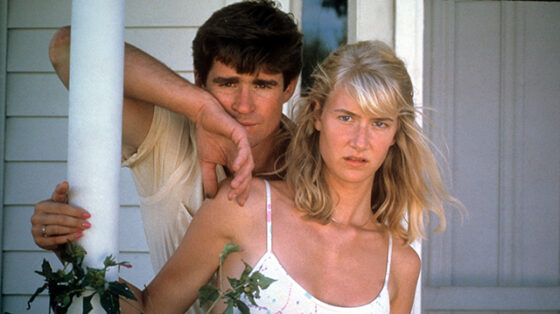

Her reflection comes as a revelation. In the safety of her bedroom, Connie (Laura Dern), the 15-year-old protagonist of Joyce Chopra’s 1985 feature debut Smooth Talk (recently released on a Criterion Blu-ray), adjusts her new halter top in the mirror, its strings crisscrossed down the middle of her chest to hang limp over her exposed midriff. The camera observes her in profile as she spins and arches her back, her gaze glued to the supple body in the reflection, luxuriating in her new possession. This scene rhymes with another that Chopra filmed about 15 years prior to the film’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, at a time when the possibility of her directing a feature must have seemed nearly impossible: in the opening shot of Joyce at 34 (1972), Chopra’s trailblazing autobiographical documentary, the filmmaker herself stands frozen before the looking glass, her hands clasped behind her as the camera homes in on the mirror and, within it, her round, pregnant belly, like an eclipse dwarfing her petite frame. “I’m really angry at being biologically this way,” she confesses in voiceover. “I want it to stop now. I’m also a filmmaker. I want to get back to work.”

The act of looking in the mirror is a slippery one for women: it reveals the boundless possibilities of womanhood and their tragic curtailment; the shallow satisfactions of vanity as well as humbling disappointment. When Connie looks at her reflection, she sees the promise of adventure in her unearthed sensuality; Joyce, on the other hand, feels the limitations of her pregnant body. Yet both women confront these defining experiences of womanhood with a searching spark in their eyes, containing a desire that surpasses reality. “[Connie’s story is about] a girl who is unformed and looking for something to happen in her life—something wonderful,” said Chopra in a 1986 interview with the Chicago Tribune. “I understand it very much…[that] deep longing.”

In Joyce at 34, Chopra recalls how, as a teenager growing up in the ’40s and ’50s, she repudiated the dream of domesticity that claimed her high-school girlfriends, who were all swiftly married off after graduation, saddled with babies, and proceeded to fade from memory. She studied comparative literature at Brandeis University and then ran off to do a year abroad in Paris, where her pals—an older crew of Swedish painters—taught her about the joys of booze and cinema. Following a stab at acting in New York City she headed to Cambridge and co-founded Club 47, a counterculture haven that played a role in the folk-music revival of the ’60s and gave a pre-fame Joan Baez and Bob Dylan early shots at the stage. (Famously, Dylan never received billing: such was the club’s allure that he played for free between sets.) Eventually, Chopra began making films under the tutelage of cinéma vérité pioneers D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock. With the latter, she co-directed the 1963 short Happy Mother’s Day, an ABC special about the birth of quintuplets in South Dakota. Then, in 1971, she had a child herself, and her struggle to reconcile family obligations and career aspirations led to her breakthrough work.

Co-directed by Claudia Weill and distributed by New Day Films—the recently founded filmmaker-run co-op that had produced such seminal works of feminist nonfiction as Julia Reichert and Jim Klein’s Growing Up Female (1971) and Liane Brandon’s Betty Tells Her Story (1972)—Joyce at 34 set the template for the documentaries that Chopra would make through the rest of the decade. Galvanized by second-wave feminism, Chopra and other New Day filmmakers set out to capture the textures and contradictions of being a woman, the ways in which women can simultaneously struggle for autonomy yet internalize their own peripherality, warping their relationships with others and with their own selves. “You aren’t really liberated if you walk around with feelings of guilt,” Chopra says in Joyce at 34, referring to the outsized remorse she feels about going to work and leaving her daughter at home, an unexpected reaction that serves to reorient her formerly critical attitude toward her mother’s homemaking. The progressive ideals of modern womanhood, empowered by the sexual revolution and the emergence (or rather, the cultural recognition) of the working woman, remained dauntingly narrow-minded, their dismissal of the “cult of domesticity” denying the potentially gratifying work of raising children and maintaining a home. Moreover, even as the women (most often comfortably middle-class women) who espoused these ideals might indeed have freed themselves somewhat from prudish traditions, this subversion also proved conducive to being absorbed and neutralized by a commercial culture that, whether crudely or cannily, continued to advance the gender-essentialist notions of patriarchal hegemony. As Chopra’s work attests, women’s liberation might only be truly achieved by disrupting and reorienting the libidinal economy of womanhood itself.

As did Reichert and Klein in Growing Up Female, Chopra sought to investigate the roots of women’s marginalization in childhood. In Girls at 12 (1975), she shows how young girls abandon their talk of becoming doctors and astronauts as they transition into adolescence, their disarming confidence crumbling into neurosis with the growing allure of boys, fashion, and makeup. Chopra’s interest in this (de)formative period of womanhood is surely what drew her to what would become the basis of Smooth Talk: Joyce Carol Oates’ 1966 short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” which the author based on a Life magazine article called “The Pied Piper of Tucson” about Charles Schmid, a grown man who cartoonishly masqueraded as a slick teenager in order to seduce, and occasionally murder, young girls. Like Oates, who was less interested in Schmid than in what he represented to the kids who fell under his spell, Chopra—who held on to the idea of adapting Oates’ story for over a decade before opportunity finally struck—frames Smooth Talk as the story of the young woman who emerges in spite of the Schmid figure’s victimization of her, rather than because of it.

The world of Smooth Talk, a sprawling suburbia of endless highway flecked with shopping centres and movie theatres, exemplifies the bleak commerciality of modern culture that, in the absence of anything else, has become the stuff of young desire itself: the chrome and neon signage beckoning lusty teens into parking lots, the mall a fluorescent playground where girls track boys with “buns.” Yet, as captured by cinematographer James Glennon, these soulless spaces seem vast and luminous, achieving a sort of aching ethereality that externalizes the restless daydreaming of Dern’s Connie, who is simultaneously the trapped princess, her gait wobbly and lethargic, her hips skipping against the wall as she walks the long, shadowy halls of her oppressive home like a disgruntled cat; the cruel brat, desperate to free herself from the humiliating role of being her mother’s daughter (that is, not belonging entirely to herself); and the burgeoning sex kitten, the grinning smooth talker and fearless thrill chaser itching to come out.

In this latter guise, Connie’s very way of moving through the world is different, as we see when she swivels her hips and shimmies her way across Frank’s, the hangout where jittery boys lean against their cars, smoking cigarettes and scoping out new ladies to take for a drive. Crucially, it’s not any particular boy that entices Connie, but rather the feelings of being desired and desiring; the thrumming music and the sticky summer air on her bare skin, the electrifying freedom of it all. “I look at you…and all I see are a bunch of trashy daydreams,” seethes her mother, Katherine (Mary Kay Place), and indeed there’s a somewhat banal quality to Connie’s aspirations, steeped as they are in a distinctly pre-Manson Family fantasy of jukeboxes, hitchhiking, and make-out points. Yet Chopra never belittles Connie’s desires, in part because her protagonist refuses simplification—not least because of the revelatory performance by Dern, who imbues the fundamentally vain and shallow Connie with an intuitive intelligence and bounding passion that dignifies even her wildest follies. Dern’s tall, lithe figure embodies Connie’s straddling of the line between childhood and adulthood, which is central to the dilemma of her sexuality: you can see it in the way she grins and bites her lip when in conversation with her suitors, communicating both nervous, girlish delight and coquettish aplomb. Meanwhile, Chopra further legitimizes Connie’s gestures of independence by emphasizing their rousing qualities: her elation in listening to loud music feels true and joyous, and her hyperfeminine beauty rituals are less forced commitments to patriarchal expectation than pleasurably soothing forms of self-care.

Even as Connie wields her fledgling sexuality like a jolly misfit (“You’re a disgrace,” Connie’s friend says to her in feigned disapproval when she lunges her body across an escalator to tease a pack of boys; “But a lot of laughs!” Connie giggles), her persisting innocence prevents her from recognizing the dangers that lurk at the edge of each of these encounters. When she plays the sexy hitchhiker to get her and her girlfriends a lift, the pickup-driving creep who immediately pulls over continually shifts his eyes to Connie in the truck’s cargo bed, howling with glee as the wind whips her body, while her sullen mates ride up front (“What’d he do, try to get you to feel his bone?” she cackles when her friend admits her unease after the trip). “You’re gonna get a fat lip if you keep this up,” says an older boy at Frank’s, in a teasing tone that nonetheless betrays his visible annoyance at Connie’s playing hard to get. Later, a steamy parking-lot tryst ends prematurely and sends Connie fleeing into the night, forced to brave what so many women can identify as a familiar horror and rite of passage: the long walk home alone at night, here along a pitch-dark country road spottily punctuated by streetlights.

One of Oates’ working titles for “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”—“Death and the Maiden”—neatly puts Smooth Talk’s Schmid figure, Arnold Friend (Treat Williams), in perspective. A man in his 30s who dresses like a teen idol, he is a manifestation of Connie’s “trashy dreams,” one of the many James Dean posters in her bedroom come to life. When he spots Connie at Frank’s, the camera pulls back to take his point of view, transforming the joyous self-expression of her dancing into his private show. He points a finger at his target and, later, arrives at Connie’s house when her parents are away, a prince in a gold Pontiac summoned to fulfill her dreams. Connie refuses his invitation to go out for a drive, but her manoeuvring is impotent: “Don’t you wanna see everything?” asks Friend, knowing her hunger for experience, her dreams of travel. In the end, he takes what’s his through the kind of grotesque persuasion that underlies the most banal, and most common, forms of assault—the kind that manages to convince the victim of her own complicity. Chilling is Connie’s equanimity when she enters Friend’s vehicle, resigned to her fate.

Who does Connie become when she willingly opens her screen door—a door that Friend would have kicked down anyway? Manipulated into submission, she slides into a fetal position as she considers her fate in the holding cell of her own home, and, with Dern’s signature wail—her eyes turned upwards, her mouth a gaping, toothless chasm—she cries out for her mother. Throughout the film, Connie had refused to share intimate moments with Katherine, keeping the details of her social life tightly guarded, and in one scene rejecting her mother’s hug with the claim that she doesn’t like to be touched (“I guess it depends on who, doesn’t it?”). For Connie, welcoming her mother’s touch would suggest that she finds comfort in maternal affection, whereas a boy’s touch swells with the excitement of the illicitly erotic, and is therefore essential to the construction of her “liberated” identity. When Connie cries out for Katherine, she effectively casts off her pretenses of maturity and nullifies her tireless efforts to be her own person; it’s a devastating capitulation, a harsh reminder that she was never above needing the security of her mother’s embrace after all.

“To me, the main thread of the movie [is] the mother-daughter relationship,” says Chopra in one of the interviews included on the Criterion disc, and it’s in Connie’s moment of tragic recognition, I think, that Chopra truly expands on her source. Friend’s uncanny menace, Connie’s “trashy daydreams,” and the idea of coming-of-age as a kind of macabre seduction are all present in Oates’ story, but Chopra and her screenwriter (and husband) Tom Cole liberate Connie’s ruinous quest for independence from utter bleakness and render it a more expansive tale about the negotiation of feminist values across generations. Chopra understands that teenagers are not merely brainless by-products of the cultural influences that inundate them, the signifiers that a predator like Friend can manipulate for his own ends. Rather, they first observe the adults in their lives, and draw their own conclusions about the world around them—which, in Connie’s case, means looking at her mother, seeing stifling domesticity, miserable, home-bound agitation, and wanting nothing to do with it. In a telling scene, Connie, making excuses for not helping with the dishes, suggests that Katherine’s irritation with the demands of keeping house is as much her own fault as any externally imposed obligation to serve her family. “Maybe you shouldn’t give them bacon every day,” she quips, naively expressing her true meaning: You don’t have to serve them. But Katherine, hyper-conscious of her own fading looks, only sees Connie’s backtalk as another cruel comment on her appearance from a slim, beautiful young woman. “Are you gonna lecture me on nutrition?” she roars.

This tension between mother and daughter pervades Smooth Talk, framing Connie’s actions as not merely forms of aimless pleasure-seeking but as ballsy, if misguided, refusals of the unhappiness she sees in her mother. Yet in struggling to wrest control of her life from a woman so seemingly out of touch with her own sad condition, Connie never looks beyond her own reflection in order to see their mutual disaffection, the ways that men only perceive them through their gendered roles (housewife or sex object) and their discomfort with demonstrating weakness. These qualities show that, despite their differences, both Connie and Katherine define their lives by a striving for something more, however inchoately or ineffectively that endeavoring is expressed. Midway through the film, Connie plays James Taylor’s “Handy Man” on the record player, a song filled with such plangent yearning that her body can’t help but move, her hips and shoulders activated into a swinging trance. Chopra then cuts to Katherine in the next room, who, hearing the music, begins swaying and singing along herself, squinting her eyes in pleasure as she strains to hit the high notes. Perhaps, Chopra suggests, there’s some hope for reconciliation between these two women in the recognition of longing as fundamental to the experience of being a woman. Without knowing it, Connie and Katherine sing as one.

Beatrice Loayza