Inbetweeners: The 2018 Images Festival

By Michael Sicinski

If you happen to frequent experimental film festivals (and, if you’re reading this, there’s a better-than-average chance that you do), you know that each of them has its own unique ambiance. Part of it, of course, has to do with the types of films shown, which in turn affects the community of filmmakers that gravitates to the event each year. But it also has to do with environmental factors, like the relative “institutional” feel of the screening venues, the presence or absence of a sense of levity, and whether the festival seems insular (not always a bad thing) or expansive.

There has always been something scrappy about the Images Festival. It could be the comparison with other, more corporate behemoths that tend to dominate the Toronto cinematic calendar. (The first year I attended, several screenings were held at CAMH, a drug rehab centre, which made for some lively Q&As.) But it’s more than that. An event aggressively dedicated to film and video’s intersection with the studio arts — the program is always divided into “Onscreen” and “Offscreen” selections — Images tends to feel less like a film festival and more like an assemblage of structured, film-like happenings, a citywide open space to wander through, occasionally sitting down but not for too long.

This is the first edition of Images helmed by new Head of Programming Aily Nash. Nash, a veteran programmer whose most recent high-profile gigs have been with the New York Film Festival and the Whitney Biennial, has a penchant for highlighting films that don’t fit comfortably into one or another identifiable category. Several of the most significant films in Images this year reflect this hybrid sensibility.

The preceding may sound like boilerplate. (What doesn’t exhibit a “hybrid sensibility” these days?) But honestly, how else to account for Nash’s exquisite taste? Because of its unclassifiable character, a film like Leilah Weinraub’s Shakedown is precisely the sort of film that falls through the cracks of most film festivals. A document in the truest sense of the word, Shakedown chronicles LA’s black lesbian underground strip-club scene of the early-aughts. Weinraub’s often rough footage is the work of someone deep inside, charting a largely unknown phenomenon from its inception to its dissolution at the hands of the LAPD. Rich with personalities, politically astute, and as nasty as it wants to be, Shakedown is a queer cultural intervention on par with Paris is Burning (1990), without the touristic undertones.

One could make similar claims — What is it? Where does it belong? — for Spell Reel, a “collaborative film” assembled by Portuguese artist Filipa César (which Jesse Cumming wrote on for Cinema Scope 71). The film is a reclamation project, comprised of decaying footage discovered from the revolutionary period in Guinea-Bissau. At that time, rebel leader Amilcar Cabral insisted that education was the true vanguard to the party, and so the post-revolutionary government saw four filmmakers sent to Cuba to be trained as socialist film workers. (Eventually their competence was “certified” by none other than Chris Marker.) Two of the original four, Flora Gomes and Sana Na N’hada, worked with César on Spell Reel, which both re-presents the recovered footage and documents the group’s various screenings of this vital historical material through Guinea-Bissau. The result is a dialectical montage reminiscent of both Harun Farocki and Travis Wilkerson. Too experimental for most documentary showcases, but too expository for many avant-garde venues, Spell Reel finds its berth at Images among the other cinematic platypi.

Much has already been written in the pages of Cinema Scope about Heinz Emigholz’s Streetscapes [Dialogue], one of the best films of 2017. The fact that it is receiving its Toronto premiere at Images speaks highly of the festival, of course, but Emigholz’s film also falls in line, in its own odd way, with Nash’s aesthetic of in-betweenism. Whereas other Emigholz films, particularly the “Photography and Beyond” works, fit reasonably well within a certain avant-garde vernacular, [Dialogue] is a bizarre departure: it’s a pseudo-narrative, a crypto-autobiography, and an old-style 1980s “talkie” in the manner of Yvonne Rainer and Mulvey/Wollen. Taking his architectural studies to a kind of reductio ad absurdum, Emigholz has both entered the picture (in the form of an actor, it should be noted) and allowed all those spaces to penetrate his own mind. Documentary and narrative intermingle, in part because [Dialogue] reflects the collapse of interior and exterior divisions.

Stark divisions are precisely what director Aminatou Echard would very much like to see break down in Kyrgyzstan, although based on the evidence in her film Djamilia, that Central Asian nation still has a way to go. Echard speaks to various Kyrgyz women about their lives, initially using the framing device of asking their opinion of Jamilia, the brash title character of Chinghiz Aitmatov’s popular 1958 novel. Jamilia, a Kyrgyz Madame Bovary, leaves her old life behind to follow her passions, something unthinkable in this deeply patriarchal culture. Echard shoots in gorgeous, grainy Super 8, and the film’s purpose becomes more explicit at the end. But there is an overall lack of cohesion that makes Djamilia far less potent than it could have been.

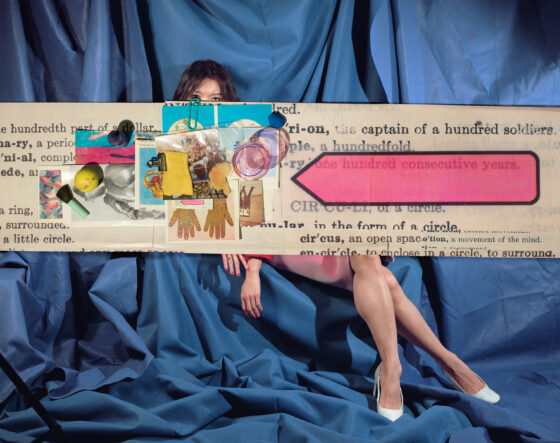

Other artists, however, are right on target — and one, in fact, strongly resembles a bizarro-world version of Target. Presenting her work in a museum context for the first time in Canada, experimental filmmaker Sara Cwynar — best known for her 2017 film Rose Gold — is a photographer as well as a filmmaker, and her work centres on design and display, in particular the visual vernacular of late capitalism. Using both the internalized language of corporate publicity and the hoarder’s logic of consumerist agglomeration, Cwynar’s images treat colour and texture as though the muted, manicured gestures of graphic design suddenly exceeded themselves, producing annual-report photos from a parallel world of nightmares. While her photos evoke the disastrousness of “plenty,” a film like Rose Gold is methodical, meting out its cult objects in time. In Cwynar, Images has found an artist working in multiple directions, but achieving similar conceptual ends.

Finally, each year the Images Festival spotlights a Canadian media artist. At long last, they have selected one of the very best: Chicago-based video essayist Steve Reinke. Although Reinke has indeed made longer works — and this year’s festival features a new one, 2017’s What Weakens the Flesh is the Flesh Itself — it is a fundamental characteristic of his work that it is interlocking and modular, the individual identity of his pieces always deepened and expanded by being seen in series. Images obliged, presenting a program of seven of Reinke’s finest, from 1991’s Joke through 2015’s A Boy Needs a Friend.

Reinke’s style is bizarre and inimitable, combining high theory, deadpan comedy, and gay content so explicit it would have made Jack Smith blush. (Ever seen an ouroboros tattooed around a guy’s asshole? Trust me, it makes sense in context.) A cultural and critical magpie, Reinke will go from making a point about resurrection myths using clips from an old Casper the Friendly Ghost cartoon to offhandedly remarking “Heidegger was the best Nazi. Not that I’m making a list or anything…” In one piece, Reinke flashes a text that reads “Marshall McLuhan is my Lenny Bruce,” and that just may explain everything. A festival like Images, committed to showcasing the work that doesn’t fit easily into the usual categories or spaces, could hardly have chosen a better Man of the Hour.

Michael Sicinski