TIFF Countdown -2: Martha Marcy May Marlene / Afghan Luke / ALPS / The Artist / Beauty / Fable of the Fish / First Position / The Ides of March / Kill List / Le Havre / The Loneliest Planet / Page Eight / Pina / Play / A Separation / Sons of Norway / The Student / Tyrannosaur

Cinema Scope 48 Preview: Martha Marcy May Marlene (Sean Durkin, US)—Special Presentations

By Andrew Tracy

By Andrew Tracy

If “indie-ness” conveys a certain generic intimation unto itself, some of the most celebrated recent independent films have also strategically adopted broader generic tactics, usually related to violence. As sensation, whether shockingly enacted or tautly withheld, has started to become an ever more important element for independents to attract the necessary attention, this has naturally led to a focus on ever more extreme situations to supply those jolts, from the feudin’ and fightin’ Southern revenge ballad of Jeff Nichols’ Shotgun Stories (2007) to the less estimable Winter’s Bone (2010), where its backwoods Nancy Drew encounters threats of rape, murder, and mutilation. Of course, unfamiliar worlds and familiar worlds made strange—an intense specificity of region, character, tone—have traditionally been independent cinema’s raison d’être; but even with the worthy films in this vein, one begins to suspect that the setting is more pretext than source, less lived reality than ready-made scenario.

The opening minutes of Sean Durkin’s Martha Marcy May Marlene nicely encapsulate this bleeding between modes. A series of neutral, uninflected shots take in a vaguely rundown farm, with about a dozen men and women working at various tasks. Apart from the passingly curious fact that all the people are rather young and have no obvious family connection, nothing seems amiss—until the camera moves inside the farmhouse to the evening meal, where the men sit at table while the women wait outside for their turn. At dawn the next morning, one of the young women quietly dresses in the sleeping quarters she evidently shares with all the others and leaves the house, the camera following her outside and then stopping to watch her swiftly cross the road and run into the woods on the other side, as a man’s offscreen voice shouts “Marcy May?” Evading her dimly glimpsed pursuers, the woman reaches a town and hurriedly eats breakfast in a local diner, where she is “caught” by the man (Brady Corbet) who had yelled for her. Sitting down in her booth (and eating her discarded breakfast), he mildly/menacingly asks why she decided to come into town by herself. When she declares that she’ll return by herself later, he unconcernedly consents, leans in to kiss her on the forehead (she shies away), and leaves.

Nicely building in both mystery and anxiety, this first sequence neatly throws the viewer off balance a few times over and stakes out the film’s formalist ground: an alternation between distanced observation and intense subjectivity, milking the disorientation and perceptual shifts of the latter to cast a pall of nameless but omnipresent dread over the former. After making a call from a payphone to a woman who recognizes her as “Martha,” our multi-monikered heroine (Elizabeth Olsen) is picked up by same, who turns out to be her sister Lisa (Sarah Paulson). As the two arrive at a palatial lakeside home that Lisa shares with her architect husband Ted (Hugh Dancy), the backstory comes thin but fast: Martha has been out of contact with Lisa for almost two years, fleeing from a guardian aunt (the sisters’ parents evidently dead) and apparently running off with a boyfriend to the Catskills. As this awkwardly reunited demi-family starts trying to share the same space, however, Martha’s behaviour—an unwillingness to eat while Ted is at the table, a lack of that social grace that precludes talking about money in the vicinity of people who have it, an unhesitant stripping down to the buff for an afternoon dip in the lake—bespeaks something a tad more amiss than teenage willfulness.

As most reading this will know long before this exegesis in extensis, the farm that Martha fled is the compound of a cult where she has resided for those missing years, ruled over by the laconically charismatic Patrick (John Hawkes), whose paradoxical rhetoric meshes appeals to communality, self-reliance, self-help, and anti-materialism with male supremacy, sexual exploitation, and incitement to violence (apropos intermittent home invasions on the abodes of the well-to-do). Durkin employs matching sound and/or image cues to seamlessly slip from Martha’s present-tense re-acclimatization to the “normal” world back into those lost times, as we see her recruited into the group, casually rechristened “Marcy May” by Patrick, drugged and sodomized as part of her rite of passage, and accepting her role as a “teacher and a leader” by taking another young female recruit in hand.

It’s one of Durkin’s real achievements in these passages that he convincingly conveys the seductiveness of this lifestyle as well as its repulsiveness. Omitting any (organized) religious element to Patrick’s bastardized pseudo-philosophy—an immediate red flag for the Blue State audiences that will largely be the ones seeing this film—Durkin allows the horror to emerge gradually, both dramaturgically and formally. In particular, one expertly measured lateral tracking shot across the farm’s foreyard successively weaves together Patrick’s velvet-gloved but iron-handed dominance, the willingly subordinated but still lively camaraderie of the group’s women, and the introduction of a new blonde-haired sheep to the flock. (The film’s cinematographer Jody Lee Lipes, who pulls off some admirable effects with darkness and desaturation throughout, warrants a large measure of praise.)

As many a magazine feature will soon remind us, however, the real story here is not the filmmaker but his lead, and the untwinned Olsen is indeed a magnetic presence. Opaque, alert, and intelligent—which renders her regurgitation of the cult’s buzz-worded, circular-reasoned maxims all the more chilling—she makes Martha’s uncontrollable, slow-burn shifts from dour/charming teenageness to verbal and physical violence in the company of the uncomprehending Lisa and Ted unerringly, viscerally effective. And indeed, it’s as a visceral object that Olsen is treated here. The Variety review’s swooning ode to Olsen’s “Maggie Gyllenhaal[-like] soulful ease and saucer eyes” on top of “Angelina Jolie’s husky voice and bee-stung lips” is not purely a matter of a single writer’s proclivities. At first glance far more reg’lar folks than the Maxim-readiness of Winter’s Bone’s Jennifer Lawrence, Olsen becomes as much a phenomenological as a psychological curiosity for Durkin’s probing camera. Distinct from the dispassionately treated sexual shenanigans at the compound, the film covertly sexualizes Olsen throughout: putting her in bikinis and clinging dresses, offering a slow-motion focus on her ass (sorry, a glass of water in her hand) as she walks through a doorway, even including a makeover scene that, naturally, leads to her most violent outburst.

There’s a retrospectively distasteful “thingness” to the use of Olsen in Martha Marcy that testifies to the cannily pitched externality of the film itself. It’s telling that Durkin forms part of the triadic directing/producing firm Borderline Films with Martha Marcy producer Antonio Campos, whose slick but shallow 2008 Haneke-aper Afterschool (produced by Durkin, and shot by Lipes) became something of a critical hot point a couple of years back. Though Martha Marcy is less overt in its Hanekeanisms than the voyeurism/technology/mass media mash-up of Afterschool—and Durkin also exhibits a far more fluid camera style than Campos’ ostentatiously static, cropped compositions—a crucial aspect of the Austrian’s modernist modus operandi is still operative: a materialistic appraisal of psychological states that eschews explanation for demonstration. What Haneke’s American acolytes miss, however, is that this technique is embedded within a thoroughgoing, Frankfurt Schooled societal critique that (despite His Eminence’s stodgily didactic public pronouncements) retains subtlety and nuance as it moves outwards to implicate a whole web of social habits and relations. Despite Paulson’s sensitive performance, the frisson between the communally indoctrinated Martha and the yuppified Lisa rarely ascends beyond the level of easy caricature—at their first breakfast together Lisa insists on showing Martha photos of their new condo space, and later brings her a kale and ginseng smoothie—while Martha’s anti-materialist outbursts are safely contained within her damaged psychosis.

It’s thus that, despite its well-learned manoeuvres, Martha Marcy May Marlene remains solidly within the genre territory that Haneke takes as a departure point in Le temps de loup or Caché (2005), ultimately having little to say about its charged subjects beyond the sum of its largely well-turned effects. Where the pointedly ambiguous conclusions of the Haneke pair frighteningly open up into the world, the defiant, Dardenne-like hard cut that ends Durkin’s film (which has elicited equal amounts celebration and consternation) simply shuts down the film’s mechanism, suturing us off from real-life horrors for the comforts of a horror flick.

Afghan Luke (Mike Clattenburg, Canada)—Special Presentations

By John Semley

By John Semley

Though he’ll probably always get a pass for his work writing, directing, and generally stewarding the foul-mouthed and deceptively kind-hearted Canadian cult comedy TV series Trailer Park Boys, Mike Clattenburg has started skirting into Apatovian waters, by all appearances half-embarrassed by his ties to straight comedy. A would-be trenchant “analysis” of the war in Afghanistan coming only about five or ten years too late, Afghan Luke casts Nick Stahl as a “wily” Canadian reporter determined to track down a military sniper who’s collecting Taliban fingers as souvenirs. When his editor nixes the idea (newspapers, as we know, hate sensationalist war reporting), this gumshoe cub reporter finagles money from his stoner buddy (Nicolas Wright), himself eager to get to Afghanistan to shoot a doc about tanks and, of course, try the hash.

Besides being less a movie and more a tired trek through ten years of yellowing headlines, Afghan Luke falls into the same tired caustic war comedy bullshit. Like a follow-the-bouncing-ball presentation, Clattenburg pokes us along as we learn that Afghanistan needs better sanitation, farmers often decamp to join insurgents when Western troops burn their narcotic cash crops, etc. and so on. The sadist-sniper story, which is it itself intriguing precisely because it is so tacky and sensational—that editor character is an idiot—takes a backseat to this tongue-tied soapboxing. Add to this some lazy, lazy characterizations (any Afghani character who hasn’t been completely Westernized is either a nameless farmer fleeing from an IED or a member of the Taliban) and Afghan Luke sputters, despite a servicable performance by Stahl. Also, to paraphrase Ricky Gervais’ character on Extras, balking at an improbable Chris Martin walk-on: “What’s Lewis Black doing at a military base camp in Afghanistan? It’s mental!”

ALPS (Yorgos Lanthimos, Greece/France)—Visions

By Christoph Huber

By Christoph Huber

Yorgos Lanthimos expands on the themes of his previous film, the unlikely Foreign Oscar nominee Dogtooth, with much more unsettling results. Again, life constitutes some form of role-play, and as the rules of the game only become clear in the process even the slightest synopsis is a major spoiler, thanks to an initially opaque construction that then unravels with near-mathematical precision while allowing for the unpredictable interventions of character obstinacy and natural environments. The story (you’ve been warned) concerns a paramedic (Aris Servetalis from Lanthimos’ 2005 breakthrough Kinetta), a nurse (Dogtooth‘s Aggeliki Papoulia), a gymnast (Ariane Labed, star of co-producer Athina Rachel Tsangari’s ATTENBERG) and her trainer (first-timer Johnny Vekris), who have formed a service-for-hire as stand-ins for their clients’ dearly departed. The company is called ALPS—their leader claiming the highest mountain’s name, Mont Blanc—and a strict regime is maintained, leading to disastrous consequences, especially once the nurse oversteps her boundaries by getting involved. The absurdity of the situations and the deadpan line deliveries suggest another dark comedy, but the undercurrents are more scary than hilarious, abetted by fragmented framing and generally outstanding camerawork by veteran Christos Voudouris (in his first feature job since New Greek Cinema legend Alexis Damianos’ 1995 epic maudit The Charioteer): often just the person closest to the camera will remain in focus, with the rest of the image reduced to an enigmatic sea of shapes and colours, the characters adrift in a barely comprehensible environment. A truly original work and a masterpiece of contemporary existentialism, confirming Lanthimos as Europe’s most pertinent hope in an arthouse cinema suffocating in the alienation-boredom of Haneke et al. Or, per the breathtaking bracketing scenes (intensely performed by Labed), life as an absurd, awful, alluring choreography, moving from “O fortuna” to “Popcorn,” devastatingly capped by play-act praise.

The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, France)—Special Presentations

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

Coming a distant second to Malick’s The Tree of Life as the most overrated film in Cannes is this latest Michel Hazanavicius pastiche (he appears uninterested in anything else) starring his regular leading man Jean Dujardin, a pastiche actor to match a pastiche director. Like the two OSS 117 movies (where director and star made their names), the attitude is a wink-wink nod-nod toward the original movie form (James Bond with ultra-nationalist and racist tendencies in OSS, the Hollywood silent film in The Artist), fetishistically making as perfect a re-creation as possible of the original’s look, rhythm and even technical requirements. That means that The Artist is a five-reeler black-and-white silent film with dialogue intertitles shot in Academy aspect ratio, with such added technical subtleties as period-proper reel-change markers and slight tint changes between reels, to say nothing of the production’s uncanny staging of late ’20s and early ’30s Los Angeles indoors and out with locations rigorously chosen for their proper period appearance, down to the look of the sidewalks and streets. (Many of these still exist around town, and Hazanavicius seems to have visited them all.) The director’s mise en scène duplications from Mack Sennett, Josef von Sternberg, Fritz Lang and Fred Niblo beg for affectionate applause, much like the movie’s scene-stealing Jack Russell terrier. The Artist, in the end, is all fetish; its telling of the fall of a Fairbanks-type silent star (Dujardin) and rise of a gal off the streets with a mean tap-dance technique (Hazanavicius’ wife Bérénice Bejo) during the transition to talkies is just a creaky melodrama that sags pronouncedly during a downer midsection.

Beauty (Oliver Hermanus, South Africa/France)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

So, it seems that the Berlin School is having an influence after all. With its single-minded concern for what its central character sees, its precisely distanced camera, its fascination with buried emotions finally exploding to the surface, and its open-ended conclusion, South African director Oliver Hermanus’ badly titled Beauty has clearly picked up on the signals that the Germans have been beaming for more than a decade (and which is vividly on view in TIFF with the brilliant three-part Dreileben, two-thirds of which is made by Berlin School filmmakers). Several steps forward from his 2009 debut Shirley Adams, Hermanus’ drama is framed through the steadily disturbing viewpoint of Afrikaans lumber company owner Francois (Deon Lotz), who, in the first shot, zooms in on the attractive young Christian (Charlie Keegan) as an object of lust. The old South African racism has, in effect, been traded in for the equally twisted psychosis of heavily closeted homosexuality, which Francois practices with silent shame as he maintains a sad, ragged marriage with his wife Elena (Michelle Scott). A work of disciplined gravity, Beauty’s reach extends beyond a man’s self-denial of his true sexuality and toward self-loathing.

Fable of the Fish (Adolfo Borinaga Alix Jr., The Philippines)—Visions

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

There are have been stranger pregnancies in the history of cinema than the one that yields a scaly offspring to a middle-aged couple in Fable of the Fish, and better, more resonant filmic satires of the Virgin Birth than this under-realized Filipino comedy. For the first 15 minutes or so, it seems that veteran director Borinaga Alix Jr. has control of the material: he frames the arrival in Manila of cash-strapped middle-aged couple Lina (Cherry Pie Picache) and Miguel (Bembol Roco) against a clash between slum dwellers and the local police, quickly establishing the idea that the grass may not really be greener in the capital—not that there’s even any grass growing on the slag-heap adjacent to their cramped new residence.

The static, observant camerawork captures documentary details of daily life on the metropolitan margins, and so it’s almost a shame when the plot starts to assert itself. Dialogue exchanges pile up establishing Lina’s loneliness in the absence of any children, and a pointed discussion about a carved statue of the Virgin Mary points towards an impending immaculate conception. Alix is trying to have it both ways here, to sincerely consider the confusion and joy of Lina suddenly giving birth to a live milkfish while also kidding the way this inexplicable event turns her and her husband into local celebrities. The effect isn’t pointedly absurd, just sort of dopey, with Picache reduced to a holy fool and Roco a boring brooder. A late, abrupt turn into tragedy is meant to give the film’s ruminations on faith and devotion (interpersonal and between people and God) some weight, but it actually just puts the flimsiness of the entire enterprise into even sharper relief.

First Position (Bess Kargman, US)—TIFF Kids

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

None of the young dancers in First Position shove symbolic stuffed animals down trash chutes or suffer from hallucinations that they are turning into swans, so this automatically makes Columbia J-school grad Bess Kargman’s documentary a more authentic examination of the prima ballerina experience than Darren Aronofsky’s already forgotten, Oscar-feted piece of crap. Considering the overwhelmingly performative nature of their lives, Kargman’s subjects—including a military brat stranded in Italy, an adopted West African orphan living in Philadelphia and a Colombian teenager whose mother admits that she was hoping for a daughter to push into ballet as he smiles sheepishly beside her—don’t seem excessively stage managed. Their ruminations on their craft are no more or less insightful than you’d expect from a group of teenagers, but they’re charming enough, and the gap between their gawky-off stage personas and the scarily flawless pros they become under the lights is compelling even if it’s familiar from any number of other documentaries about underage prodigies.

The same goes for Kargman’s structure, which of course cuts between each dancer’s training process en route to a big international competition, a prefab arc that any director could have come up with. At the same time, Kargman smartly keeps out of the way of the performances themselves, keeping the editing and crowd reaction shots to a (relative) minimum and preserving the delight of watching bodies move effortlessly through space, a quality more important in this case than originality. So yes, First Position is conventional (it’s easy enough to imagine it being sold as “Spellbound with pirouettes”), but not every documentary has to break new ground. By giving us an intimate purview on people doing interesting, physically impressive things, First Position justifies its glossy, festival-circuit-ready existence.

The Ides of March (George Clooney, US)—Gala

By Christoph Huber

By Christoph Huber

A well-acted, competently directed “So what?,” George Clooney’s fourth feature as director follows an idealistic, ambitious campaign press secretary (Ryan Gosling) during the heated last days of a heavily contested Ohio presidential primary. Clooney himself plays the (liberal) candidate who wholeheartedly takes a stand (not always plausibly, but certainly showily) for progressive positions, a bid for integrity that quickly falters in a convolution of treacherous manipulations, sexual intrigues and pervasive lies. “Politics corrupts” is the bottom line of this glibly cynical two-word-movie, and Gosling makes a good-looking poster boy for the illustration of this banal adage, while other members of an impressive cast do their best to bring their predictably stock characters to life despite their supposedly complex natures never being allowed to transcend the level of simple turncoats. Paul Giamatti and especially Philip Seymour Hoffman as the press secretaries of the opposing camps are particularly good (the latter occasionally evokes an actual human being), while only poor Evan Rachel Wood, through no fault of her own, is saddled with a thankless victim part that exemplifies the worst tendencies of a script (by Clooney, pal Grant Heslov and Beau Willimon, author of the play the film is based on) that indulges in feeble cliches disguised by liberal “ambiguity.” If Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck., with its harking back to ’50s television (and, implicitly, the wave of ’60s political movies often signed by former TV directors) felt like a nostalgic evocation of commitment in media, The Ides of March surrenders wholeheartedly to current corruption, illustrating in the process that the “political” movies from Clooney’s gang since Syriana are not misguided attempts to ressurect the rich objectivity of Otto Preminger, but rather today’s equivalent to the lazy pandering of Stanley Kramer. You go, Brutus!

Kill List (Ben Wheatley, UK)—Midnight Madness

By Mark Peranson

By Mark Peranson

All hail Satan, and, while we’re at it, Ben Wheatley. The future of British cinema has rapidly become the present, as the promise of Wheatley’s wild 2010 debut, Down Terrace (a kind of low-rent Sopranos in Brighton) is fully realized in the insane and terrifying Kill List. Like Down Terrace, Kill List is a genre mash-up, beginning as a darkly comic kitchen-sink affair in the form of verbose improvisatory domestic scenes: two couples have gathered in the suburbs for dinner, and soon the dinner party veers into the territory of emotional violence; it’s clear something’s amiss. The two thickly accented war veterans, Jay and Gal, are grappling with some kind of post-traumatic disorder. (Or so it seems—it’s pretty damned hard to make out most of what they’re saying, and it doesn’t help that Jay’s wife is Swedish.) Hints are dropped of something that’s happened “in Kiev.” A new potential employer has entered the scene, and once Gal gets Jay on board, the real horror (and the real movie) begins as these out-of-work contract killers take on one last job.

And what a job it is. The staccato nightmare that ensues—the “kill list” part—is a compendium of intense, brutal violence the likes of which have not heretofore been seen in the History of Cinema. There’s some extremely screwed-up shit going on here, but it’s not just for the gratuitous Noé-like point of shocking the audience, many of whom will in fact leave the cinema as mentally and physically scarred as Jay. Wheatley has said he’s dealing with the erosion of the whole social contract in England after the Iraq War and the recession, and maybe the recent riots have proven his point (if the point needed to be proved at all). In all seriousness, I can’t remember being this disturbed at the movies, and in this day and age, that’s certainly saying something.

Le Havre (Aki Kaurismäki, Finland)—Masters

By Kong Rithdee

By Kong Rithdee

Wit, warmth and a pineapple: they come through in Le Havre the same way your eccentric uncle, half-drunk on Finnish vodka yet fully in control of his craft, would relate you a modern-day European fairy tale, complete with human smuggling, multiculturalism, and a sympathetic inspector accessorized with the aforementioned tropical fruit. All you’ve come to expect from an Aki Kaurismäki film you’ll get here: the dry humour, working-class camaraderie, retro squalour, poker-faced humanism, Kati Outinen. Moving away from Helsinki blues, Kaurismäki finds his hero in Marcel (the excellent André Wilms), a financially struggling French shoeshine living with his wife (Outinen) in an unglamorous quarter of the titular Normandy port town. Chance brings Idrissa (Blondin Miguel), a black boy washed up on the French shores as part of human cargo, to Marcel’s door, and the Frenchman decides to hide him from a snooping inspector while plotting the boy’s escape. The tale is only less Bressonian because Kaurismäki, surreptitiously, proposes hope and smile even in the direst situation. And if Le Havre ultimately feels a little slight, it’s because of the minimal acid and undercurrent of everyday tragedy that makes his best films memorable. Otherwise, it’ll send you out of the cinema hopeful and happy.

The Loneliest Planet (Julia Loktev, US/Germany)—Visions

By Mark Peranson

By Mark Peranson

Based on Tom Bissell’s short story “Expensive Trips Nowhere,” Julia Loktev’s bracing second feature is a world apart from her debut Day Night Day Night, but retains that film’s tense, female-centric perspective in narrating a single-minded story about the shattering of two psyches. The set-up: a young couple, Nica (Hani Furstenberg, striking) and Alex (Gael Garcia Bernal, never better—as half the film he is silent), recently engaged and possessing a mild, entitled arrogance, backpacking through a foreign country. (Lonely Planet, get it?) After partying their way through some small villages, they hire a shifty local guide (Bidzina Gujabidze) to lead them into the deserted Caucasus mountains and valleys. The film’s tournage must have proven exceedingly challenging, as Loktev often shoots handheld travelling shots through rocky terrain; big kudos to Chilean cinematographer Inti Briones, who worked repeatedly with the late Raul Ruiz.

And then something shocking happens—it’s not fair to say what this game-changing event is, but, then again, Loktev never makes it clear what it signifies, nor is it ever discussed between Nica and Alex. We move to a place beyond language, reminiscent of Antonioni or the Van Sant of Gerry, where the stunning backdrops of the Georgian countryside transform from emblems of freedom to looming clouds of doom, with Richard Skelton’s haunting music providing an appropriate backdrop for hikers being dwarfed by landscape. Keen observers will also notice a slight change in the camerawork, plus the framing, with scenes of all three protagonists together: their couple has become in essence a threesome, with fates intertwined, and support needed more than ever. A film about small gestures, about silence and the need for forgiveness, about being close to someone but being psychologically miles apart, The Loneliest Planet is a memorable evocation of a relationship and a haunted place, intertwined.

Page Eight (David Hare, UK)—Gala

By Michael Sicinski

By Michael Sicinski

Here we have the rare film that manages to evoke tedium through much of its running time, only to evoke genuine interest in the home stretch in direct proportion with an increasing level of ire and disbelief. What putters along as an over-written, tight-assed BBC teleplay about the twilight of Cold War relics serving Her Majesty at MI5 eventually mutates into a crass apologia for the New Geopolitics, wherein any attempt at maintaining ethical consistency, much less a global vision, is hopelessly passé. Bill Nighy, for my pounds sterling one of the most overrated thespians on the contemporary scene, is Johnny Worricker, an old spy so wrongheadedly devoted to The Company that he neglected his wife (Alice Krige), who then married his ostensibly more humane desk-jockey supervisor, Benedict Baron (Michael Gambon). Trouble begins when Baron comes into possession of an intelligence file relating to American “black sites” for extraordinary rendition. According to the titular p. 8, Prime Minister Alec Beasley (Ralph Fiennes, channelling Tony Blair as a Hugo Boss model) knew about it, but kept it from his Home Secretary (Saskia Reeves), MI5, and the entire British intelligence community. At this point, Page Eight is pitched between an unfunny In the Loop and a junior-grade The Ghost Writer. It seems that Blair’s bum-licking of the US is a trauma the UK is still working through, many of its liberal artists apparently every bit as obsessed with sovereignty loss as Nick Griffin. But as various characters, including rival Jill Tankard (Judy Davis), keep informing Worricker, “It’s the 21st century,” and rational-actor flexibility is where it’s at. So by the end, Worricker sacrifices all his grand ideals for a kiss from the young woman across the way (Rachel Weisz). Alas, the end is Nighy.

Pina (Wim Wenders, Germany/France)—Masters

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

Wim Wenders, quite possibly Europe’s worst working filmmaker, only gets worse with this atrocious 3-D “love letter” to the late German choreographer Pina Bausch. No two figures in recent German culture are perhaps less suited for one another: Wenders and his tone-deaf approach to human beings, his thoughtless imposition of movie lore and memories onto every moment, his spineless manner of deferring everything until his films are about nothing; Bausch and her absolute self-conviction, bold physicality, fierce attention to details and moments, total belief in her dancers to execute her seemingly impossible work teeming with ideas. Not surprisingly, with Bausch no longer around to correct him, Wenders screws up everything as he tries to film her Tanztheater Wuppertal company. His camera, for one, intrudes on the dancers’ space, in a crude attempt to bring the viewer closer to the action. (Bausch once demanded that a film crew documenting one of her performances remain off-stage, as close to the audience’s perspective as possible; after all, it’s from this view where she intended her work to be seen.) Worse, the pieces are broken and cut up, most egregiously in the wholesale obliteration of Bausch’s masterpiece “Café Mueller,” which realizes its dramatic and conceptual power only when viewed in its totality and in continuity. Wenders’ slice-and-dice game makes one wish that Bausch would rise from the grave and give him a firm kick where it counts.

Play (Ruben Östlund, Sweden/France/Denmark)—Visions

By Richard Porton

By Richard Porton

While occasionally more plodding than playful, Ruben Östlund’s ingenious foray into conceptual cinema succeeds in both skewering the pretensions of seemingly liberal and tolerant Swedes and challenging the audience’s own preconceptions. Inspired by an actual incident in Gothenburg, Sweden’s second-largest city, Östlund casts a harsh, and frequently funny, light on Scandinavian racial tensions by focusing on the efforts of some clever kids of African origin to swindle younger, wealthier schoolchildren through sheer force of will instead of violence. Even though their victims have ample opportunities to escape or fight back when threatened with the loss of their wallets and cell phones, the African kids hold the upper hand because their well-heeled prey are intimidated by both the race of the scam artists and their own liberal conditioning. Once a few feuding parents arrive on the scene, however, the veneer of Swedish liberalism dissipates and the racism that simmers below the surface of many Scandinavian societies rears its head with bleakly comic results. (A seemingly unrelated running gag about an abandoned child’s cradle blocking the aisle on a passenger train also pokes fun at the way Swedish decorum unravels in stressful situations.) Dominated by a disciplined use of fixed camera positions and an aesthetic that simulates surveillance video, Play often recalls some of Michael Haneke’s early provocations as well as the narrative stance employed by Corneliu Porumboiu in Police, Adjective. Although less rigorous than Porumboiu’s film, Östlund’s wry examination of the indignities of class and race is a welcome riposte to the cliches of the standard social problem film, whether exemplified by Hollywood variants such as The Help or the feebler films of Ken Loach and Michael Winterbottom.

A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, Iran)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Kiva Reardon

By Kiva Reardon

Winner of the Golden Bear at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, A Separation focuses on two families whose lives become well and truly entangled. Initially, the crux of the drama seems to be that Simin (Leila Hatami) and Nader (Peyman Moaadi) are seeking a divorce: she wishes to leave the country, while he refuses to abandon his aging, Alzheimer’s-stricken father. Complicating matters further is the custody of their 12-year-old daughter, Termeh (Sarina Farhadi), who is reluctant to side with either parent. After Simin moves out, a lower-class woman, Razieh (Sareh Bayat), is hired to care for the father, and her lack of qualifications is only the beginning of the problem; her decision to conceal her pregnancy from her new employer sets off a massive snowball effect of complications.

There’s potential for melodrama here, but writer-director-producer Farhadi eschews grandiosity. Through small moments ranging from the mundane (Simin pays movers in her building to clear the stairwell of a dresser they were planning to abandon two floors into their journey) to the pointed (when Nader’s father soils himself, Razieh can’t help him to change his clothes without calling a religious hotline and investigating the consequences of assisting a naked man), we become aware of the stifling effects of bureaucracy, class structure and a rigidly maintained sense of decorum on people trying to follow the dictates of common sense. A Separation paints a picture of a society which is rapidly changing yet fundamentally stagnant; the film is a drama of intractability. This is the unresolved and pertinent question that Farhadi leaves us with at the end, as legally (and visually in the final shot) Nader and Simin are separated—the culmination of a film filled with scenes of characters being shut out of rooms or left waiting behind doors. The representations are complex: Simin represents a modern Iranian woman, with her loose hijab and dyed red hair, but her desire to leave the country feels more impulsive than any sort of statement; Nader, meanwhile, is sympathetic and caring (Simin describes him as a “good decent person” at their divorce hearing), but we can see that he’s desperately holding onto the decaying history and tradition his father represents. Throughout the film, both prove to be less than ideal parents, using Termeh even as they both claim to be doing what’s best. It thus makes sense that of all the hard choices in the film, it is Termeh’s decision that is left offscreen. Hers is the question that many Iranians wait to have answered: what next?

Sons of Norway (Jens Lien, Norway)—Contemporary World Cinema

By Adam Nayman

By Adam Nayman

“It’s hard to be honest if you don’t know what you mean.” That’s good advice for any 14-year old boy—or for anybody, really—and it sounds all the more wise when it’s coming from a nubile, stark-naked young woman. She’s a hippie, and the subject of her observation is a punk, or at least an aspiring one: Nikolaj (Åsmund Høeg), the intelligent but impressionable son of permissive hippie parents who discovers the Sex Pistols around the time that his mother dies in a car crash. This results in a mash-up of adolescent rages that result in him cutting off his hair, sticking a clothespin in his cheek and telling anyone who’ll listen that he’s an anarchist.

He doesn’t know what he means, but in his own mind, he’s being honest, and it’s nice that Sons of Norway permits its young hero such contradictions. The film is open-hearted where Lien’s previous film The Bothersome Man was smugly closed in on itself, a gruelling sojourn in a sterile, art-directed realm that was implied to be Hell and which was probably supposed to be a statement about Norwegian society. Where that film’s abstractions were facile and deadpan style stillborn, Sons of Norway, by contrast, sets itself in a real historical moment (the late 1970s) and examines the impact of the three-chord musical revolution—so familiar from so many American and British movies— on a peaceable, left-liberal culture whose traditions are not exactly crying out for a violent overturning. The insights aren’t brilliant, but Nikolaj’s relationship with his father (Sven Nordin) is affectionately sketched. This bearded, benevolent ’60s refugee eagerly encourages his son’s acts of rebellion (and drags him to a nudist colony, which is where that aforementioned naked sage comes in). Lien is not a subtle filmmaker, and he has a few really bad ideas, like permitting John Lydon (who executive-produced the film) to make a self-flattering, Wayne‘s World-esque cameo. But he’s crafted a watchable film in the dread genre of the coming-of-age tale, and if that’s not an achievement worth truly celebrating, it’s at least duly noted.

The Student (Santiago Mitre, Argentina)—City to City: Buenos Aires

By Robert Koehler

By Robert Koehler

When Santiago Mitre’s film about a Buenos Aires university freshman’s full-bore dive into student politics was first shown at BAFICI, many Argentine colleagues were concerned that a North American audience might not fathom the political reference points. Now, it may help to have some foreknowledge of Argentina’s unique admixture of leftist and rightist ideologies, especially as they’re manifested in Peronism; certainly, some sequences’ full effect stems from ingenious re-creations, and mock imitations, of past pivotal political events. But The Student nonetheless sustains itself beautifully absent any viewer-supplied footnotes. It’s in the classic Bildungsroman tradition, in which the young man (Esteban Lamothe, like a present-day Werther) arrives in the city from the provinces to find himself and his fortune—in this case, his hidden capacity for playing ruthlessly calculated politics on the college level, eventually spilling over into nastier off-campus affairs. The film finally becomes about the mechanics and cost of promises made and betrayals executed, and the ugly spectacle of ideas played out with unintended consequences.

Tyrannosaur (Paddy Considine, UK)—Special Presentations

By Jason Anderson

By Jason Anderson

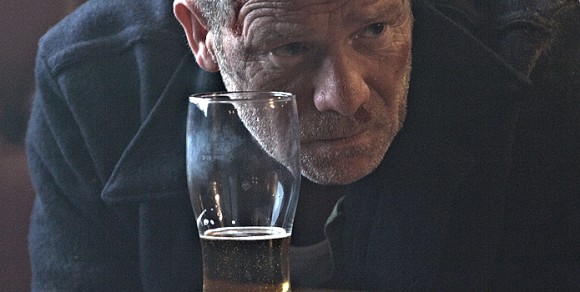

The ferocious feature debut by Paddy Considine, Tyrannosaur is the latest example of a curious subset of British cinema: first-time directorial efforts by much-cherished actors bent on venting their rage at all of God’s creation. Indeed, Tyrannosaur may take several steps beyond Gary Oldman’s Nil by Mouth and Tim Roth’s The War Zone toward a new extreme in Limey nihilism: its closest kin could be Gaspar Noé’s Seul contre tous, a relentlessly vicious study in misanthropy that Tyrannosaur tries to top straight out of the gate by having its protagonist—a hot-tempered, alcoholic widower played with all due fury by Peter Mullan—kick his dog to death. And this before the opening credits.

Light entertainment on the order of Le Donk and Scor-zay-zee—the rock-world mock-doc that marked Considine’s latest collaboration with pal Shane Meadows, for whom he also scripted Dead Man’s Shoes—is most definitely not on offer. Essentially an extended version of Considine’s 2008 short Dog Altogether (which also starred Mullan), Tyrannosaur is a portrait of England at its most vile and violent, a country of small shabby rooms and perpetual pub brawls. Though Mullan’s thuggish Joseph is happy to dish it out, he still has the capacity for regret: for one thing, he misses his dog once he’s through with his tantrum. He may even have something like a tender side, which gradually emerges in his encounters with Hannah (Olivia Colman), a thrift-shop owner who’s trapped in a hell of her own thanks to her abusive husband James (Eddie Marsan).

Clearly, there’s some healing to be done, but Considine’s not terribly interested in providing a respite from his horror show of pain and cruelty. Yet while Tyrannosaur may only have one-and-a-half notes in its emotional register, Considine plays them with an unflagging sense of passion and purpose.

cscope2