From the Other Side: Exiled in Trumpland

By Roberto Minervini

I moved to the United States on October 22, 2000, to work as an IT consultant in New York City just a few days before the infamous presidential election that saw George W. Bush lose the popular vote and ultimately “defeat” Al Gore, after the conservative Supreme Court controversially halted the Florida recounts. Then the harsh winter came, and it made me wonder why the hell I had left Spain, where I had been living happily since 1994. A handful of months later, two planes brought down the World Trade Center. My client, a company called eSpeed, had its office in one of the towers. With my client’s demise, I lost my job shortly thereafter, on September 19, 2001. I became a “victim of 9/11” and got compensated by the state of New York with 18 months of full salary, with which I paid for an MA in Media Studies at the New School. Last but not least, once again the US went to war, this time in Afghanistan. Hence, after one year living in America, I thought I had seen it all. But boy, was I wrong. Fast forward 15 years, and I had to witness the election of a corrupt, sadistic, real-estate mogul/television personality as the next president.

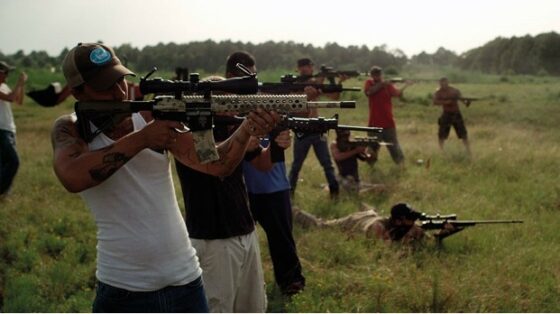

However, unlike Bush’s election, Donald Trump’s victory did not come as a surprise to me. If anything, I expected him to win by a larger margin than he actually did. For the past eight years of the Obama administration, I have been closely observing the germination and proliferation of right-wing grassroots movements in America. As I found myself based in the South—in Houston, Texas, of all places, for reasons beyond my control—I was given the opportunity to come in contact with an entirely different face of America, far from the liberal elite milieu of New York City. Almost anachronistic at times (as seen in the omnipresence of the Confederate flag), their self-reliance through armed association brought back memories of my childhood spent with a babysitter from the Italian armed revolutionary leftist group, the Red Brigade, and I was drawn in by the intensity and conviction with which they held their political beliefs. I made a film with the Southern militia called The Other Side and spent enough time with them to understand a few things that have become deeply relevant at this point. Thus, with some certainty I can say that the surge of these movements is no fluke, nor is it a passing trend. In fact, their key principles—xenophobia, homophobia, misogyny, an undying pride in family values and heroism, and the fear of a strong central government—are deeply engraved in the collective unconscious of conservative America. For the last ten years while living in Texas, what I have come to learn most of all is that people in the Midwest and the American South are ferociously angry.

These are regions where less than a quarter of the population has a college degree, and yet people claim to know their history. During the filming of The Other Side in 2013 and 2014, in East Texas and Northern Louisiana, some members of the anti-government militia I was following explained to me how their distrust of the federal government and their staunch demand for sovereignty over local territory stem directly from the Declaration of Independence. Consciously paraphrasing the founding document of American politics, the militia members told me that “their citizen rights come from God and not from the government,” and that “citizens have a right to self-government” and to “start a revolution, if necessary.” I wasn’t surprised to hear that. After all, the Declaration of Independence is little more than a declaration of war, written by a group of rich friends with a frat-house name (the “Founding Fathers”). However, such an answer revealed the fact that conservative America feels as threatened by the federal government today as Revolutionary America did more than two centuries ago, when the enemy was the United Kingdom.

Instead of a revolution, Southerners want devolution. They think that they would be better off with a more powerful local government than with an allegedly intrusive central one. This false belief is partly due to the chronically low level of political knowledge in the US. (My illiterate grandfather knew more about the Cold War than Reagan did.) In reality, things work in the exact opposite way: historically, whenever and wherever local governments are incapable of effective policy making, people lose trust in the federal government. A clear example is the malfunctioning of Obama’s Affordable Care Act, whose introduction angered more than half of the US population. Those who have seen The Other Side may remember a scene where a woman, wearing an Obama mask, pleasures a man with an explicit “oral Obamacare” act. Despite the bravado-filled mockery displayed in the scene, a more serious statement is being made. These people reject outright federal interventionist policy, regardless of whether it benefits them or not—as a matter of fact, the Affordable Care Act’s removal of pre-existing conditions as a basis for denying coverage is a very desirable feature for every American.

Similarly, local governments in Republican states employed a form of dirty-handed political obstructionism by refusing to finance the new law, and doctors began to opt out of the Obamacare exchange plans in droves, thereby bringing about the Affordable Care Act’s inevitable downfall. (Because I live in Texas, the state that led the crusade against the Affordable Care Act, there are remarkably few doctors willing to accept my insurance plan.) Hence, the failure of the new healthcare law started from the bottom-up, led by local governments and reactionary grassroots movements. Yet, President Obama and the central government took the blame—and with the Republicans controlling Congress since 2014, Obama has been unable to improve the healthcare law.

Nevertheless, the anger of conservative Southern and Midwestern Americans cannot, must not, be dismissed as a mere case of collective political blindness. That is the mistake that the progressive elite has been making over and over, for years, alienating itself from the masses. There are other, more plausible, reasons for conservative America’s dissatisfaction with Washington, and for the rise of right-wing extremisms. One of the main reasons has to do with economics. The US has transitioned from being a manufacturing to a service economy at lighting speed. In just 25 years, industry sectors like healthcare and social assistance—yes, even in Texas the latter is the leading industry—scientific and technical services and retail have grown exponentially, while energy, automotive, and other goods-producing sectors have plummeted. In 2007, profits in the manufacturing industry hit an unprecedented low, and millions of blue-collar workers lost their jobs. Since then, the majority of these workers have had little to no chance to reinvent themselves and be re-integrated into the job marketplace, especially with the current dysfunctional, underfunded US public education and professional training system.

The South and the Midwest are the hotbeds of blue-collar workers. Some of my Texan friends are welders, a noble profession that has become a rare breed in post-industrial America. These days, most of them struggle to stay employed and to make ends meet. “There’s not enough work for all of us,” they all told me, “and we aren’t making much money anymore, and we’ve got to pay for taxes, health insurance, and benefits.” Not to mention having to pay for all the millions of illegal immigrants in the country who are using taxpayer-funded welfare programs.

People are fed up around here. And, historically, when America’s working class is fed up, they vote Republican. This may sound counterintuitive to those unfamiliar with American politics—after all, Republican governments are the ones responsible for drowning the country in the muddy waters of economic liberalism, nonchalantly cutting taxes for the rich, and crippling the welfare system. But in the late ’60s, during wartime, Nixon coined the term “silent majority” in reference to the hard-working citizens who were taken advantage of by the ungrateful federal government, despite the fact that the working class was the “catchment area” for army recruits. So, in one shot, Nixon granted blue-collar America the status of victims and heroes. With two simple words, he won them over. And today’s Republicans, with the Tea Party and Trump leading the way, have widely and effectively adopted Nixon’s rhetoric and added to it a new pledge of economic protectionism, vowing to renegotiate NAFTA to the benefit of American workers, or threatening to withdraw completely. During the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, conservative movements started a crusade against the Obama government, despite being the ones who embraced the free-market orthodoxy that led to the crisis. The crusade was effective, and the Democrats lost the Senate majority in the 2014 elections. And during this past presidential campaign, Trump called for the working class to unite and follow his lead, to revolt against the establishment that has pushed the economy to the verge of collapse. Right-wing demagogy always works when times are hard.

But apart from denouncing the lack of job opportunities, my blue-collar friends said something else to me: “There are too many people willing to work for cheap.” Ah, here comes the other main reason for the tsunami of anger in the South-central red states: Mexicans. “They hang their laundry out the window, they do jobs white people are too cool to do themselves. I don’t care if it starts a race war, I don’t care if it brings every bigot out of the closet and gets every brown skin savage beaten out on the street, in this country you speak English or you get out.” These are the imagined words of California Governor Pete Wilson in 1994, on the occasion of the passing of Proposition 187, as performed by Chicano hardcore band Brujería in one of my favourite songs, “Raza Odiada (Pito Wilson).” (The song starts with the invented assassination of Wilson at the hands of Mexicans during his victory speech.)

Wilson is an abominable subhuman, but he was not completely insane. As California was floundering in a massive recession, he was skilfully voicing the disquiet of the population, and was doing so with the full backing of Republican Party officials. Designed to ban illegal immigrants from using a wide array of public and social services, Proposition 187 passed with a staggering 58% of the vote (luckily, later on, a federal judge issued an injunction against the state of California and blocked it). Interestingly, the standard bearer in favour of the proposition was soon-to-be Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, who is now being considered by Donald Trump for any number of cabinet positions, alongside a number of other deplorables. There is no doubt in my mind that Trump is the second coming of Pete Wilson—this time with a vengeance. The large electoral support he received is a sign that very little has changed in America in the past two decades. It remains a largely economically divided, pathologically anxious, and inherently racist country, brainwashed by fallacious information on crime rates (the perpetual lie that non-whites are more crime-prone than whites), national security threats, and, last but not least, the ever-incumbent fear of the loss of individual freedoms. It is a country where tolerance is interpreted as forbearance, more than justness. Sometimes I still wonder why I left Europe in the first place—even though my native country elected Berlusconi and had to endure 20 years of a right-wing regime, and Spain’s current Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, is the reincarnation of the Caudillo.

But then again, here in the South there are still people who surprise me daily, and whom I love deeply. Like Tim, the patriarch of the Texan goat-farming family featured in my film Stop the Pounding Heart (2013), who said to me that he was going to vote Democrat for the first time in his life, so as not to have a prejudiced, immoral, and unjust president like Trump. Or like Linda, the mother of the young bull rider featured in the same film, who would like to have Willie Nelson as the next president. The South is the real deal. For better or worse, this is my home.

As a filmmaker, I can’t help but consider how cinema has been reacting to this whole political bedlam. The political apathy that permeates the contemporary film world is nothing new, and I am not going to comment on that. But what really worries me is the surge of a new wave of philistine cinema, which is producing covert-yet-not-so-subtle nationalistic, reactionary work, sugar-coated with the recipe of mainstream productions. There are several examples of this filmic trend—even in the arthouse world—but I am an active filmmaker and cannot afford to make too many enemies in this business. Hence, I am only going to mention one exemplifying case: Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario (2015). On the surface, it appears to be just another film about the dirty war on the Mexican narcos led by the US. A war where there are no winners, but there are no clear losers either; where the hero (an American FBI agent, of course) is too morally upright to even have a clue about what’s really going on in Ciudad Juárez; where the antihero is a Colombian phoenix who emerges from the ashes of his own dark past to begin a new life cycle. All in all, it’s the same old futile story, and was successful enough that the sequel, Soldado, directed by Stefano Sollima, an Italian director who built an entire career out of milking the cash cow of organized crime’s stereotypes, is currently in production for a 2017 release.

However, what I found most disconcerting is the image of Mexico that the film delivers. Ciudad Juárez is portrayed as a city in civil war, where bombs explode and gunshots are heard nonstop throughout the day, and where countless decapitated corpses decorate the city streets: a place where even the FBI, the CIA, and the Army are afraid to go. While watching the film, I remember wondering if Denis Villeneuve and his collaborators had mistaken Ciudad Juárez for Fallujah, and Mexico for Iraq (though I must say that many Mexican filmmakers have not been any less beholden to the marketability of the immigration issue and the extreme violence in their own country, which is even more morally reprehensible). Trump employed similar tactics of generalizations and stereotypes when he claimed inner-city crime had reached record levels and compared the violence in Chicago to a war-torn country. (On the contrary, violent crime has been on a steady decline since the ’90s and reached its lowest point in decades in 2014.)

As for the point Sicario was trying to make, some of my crew members live in Ciudad Juárez, which is now safer than many cities in the US, including New Orleans where I am working now, and I can assure you that they enjoy a pretty normal life, not one of constant danger. What is actually dangerous is this boorish anti-Mexico, pro-US propaganda. And given the times in which we live, with such a beastly insurgence of anti-immigration movements in the US, to make a film of such reactionary vigour is to be either a careless entertainer or a ruthless fascist. Granted, I do not know anything about Denis Villeneuve, except that he is Canadian. Hence, he should be tried in his own country and by his own citizens for his moral and political crimes—and the same goes for the unnamed Mexican filmmakers. But to his American screenwriter and producers I say: “Shame on you. You deserve Donald Trump.”

Roberto Minervini