Exploded View | Paul Sharits by Chuck Stephens

“One of his best-known works, N:O:T:H:I:N:G, features a light bulb and a chair.”

Paul Sharits remains the most structurally precise and disturbingly unknowable experimental filmmaker of the late 20th century, much written about and yet still wholly enigmatic, his work spare, blunt, baffling, often enraged, and always overwhelmingly beautiful. P. Adams Sitney long ago claimed Sharits’ N:O:T:H:I:N:G (1968) as one of only three “flicker films” of its era to matter. (Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer [1960] and Tony Conrad’s The Flicker [1965] were the other two.) Indeed, Sharits has always had his explicators and advocates, then and now. There are several in- and out-of-print books and pamphlets devoted to his numerous films, “inert film” paintings, unclassifiable sculptures, tightly graphed squiggles, and infinite-loop “locational installations,” Yann Beauvais’ lushly illustrated Paul Sharits (Les Presses du Reél) chief among them. A huge archive of Sharits material is available at www.mikehoolboom.com, and Re:voir has produced a DVD of three of his quintessential “mandala” films: Piece Mandala/End War (1966), N:O:T:H:I:N:G, and T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968). Yet there always seems to remain something more to be said about Sharits (born in Denver, CO, 1943), and not just when one comes across a howler like the “description” of N:O:T:H:I:N:G quoted above, found in The Buffalo News’ lengthy obit for the filmmaker, who took his own life in 1993, on his 50th birthday.

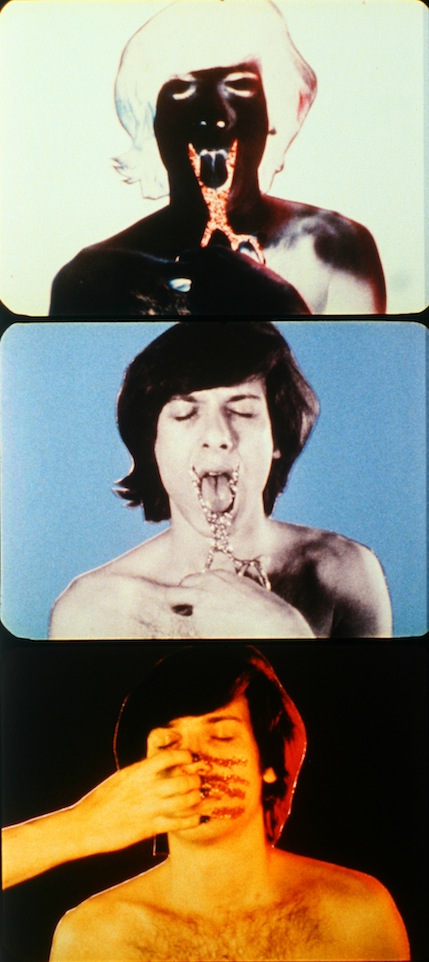

Yes, both a chair (repeated still images of a wooden one, in the process of toppling over) and a light bulb (in a series of cartoon illustrations, emanating little lines of “light” and eventually emptying out its contents) are featured in N:O:T:H:I:N:G. Combined, they comprise less than two of the film’s 36 minutes, the rest of which consists of static frames of solid colours edited in algorithmic patterns to produce sublime cascades and dazzling conniptions of flickering, drifting, flaring, and dimming hues: Rothko ochres and Woodstock grass-stain greens give birth to phantom shapes and shadow motions; the wall dissolves in waves of toy-boat blues and race-riot reds. (“I like the colours,” someone says, admiring a ’60s concert poster in Soderbergh’s The Limey [1999]. Peter Fonda concurs: “We all did.”) In T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G, positive and negative still images of poet David Franks posed against a variety of solid-colour backdrops—sometimes cutting off his own tongue with glitter-covered scissors, sometimes suffering a series of glitter-stained fingernail scratches across the face—attain a fugue state of rapid alternations while the soundtrack loops and stammers the word “destroy” again and again, finally destroying the intelligibility of the word in the process.

There is often violence done to sound and image in Sharits’ cinema (and a strain of largely self-destructive violence that ran through his life), though his professed goal was enlightenment, not annihilation. Still, it may be the most crassly material concerns of Sharits’ cinema that remain the most haunting, and the most difficult to fully engage. Amos Vogel’s Film as a Subversive Art presciently noted that Sharits’ structuralist fields of colour and patterns of meditative pulsation were always balanced by and directly related to the provocations of “neo-Dada and Pop.” Hence the staggering, double-screen meta-project Razor Blades (1965-1968) and its shattered taxonomy of sprinkled stars, stuttering stripes, naked college students, Fluxus instructions on how to wipe your ass, and the preparation of a raw, red steak, cleft by a straight razor and covered with shaving cream. Sharits explained that it was all part of a vision of “the Life Cycle” in which “mundane activity [is] slashed open, revealing the positive-negative dynamics of sexuality, birth, growth, clashes at levels of reality, horror, confusion, absurdity, suicide; then, the ‘other side’ of death-filled visions of life—the razor used to slash a wrist becomes Medicine (the life-giving scalpel)…ends becoming beginnings.”

Destroydestroydestroy. Create.

Chuck Stephens