Fluid Frontiers (Ephraim Asili, USA/Canada) — Wavelengths

By Jesse Cumming

Published in Cinema Scope 72 (Fall 2017)

If it is not here

It must be there

For somewhere and nowhere

Parallels

In versions of each other …. where

Or even before something came to be

—Sun Ra, “Parallels” (1970)

Described as “A Video Film on Space and the Music of the Omniverse,” Ephraim Asili’s Points on a Space Age (2009) is an appropriately free-form documentary about musician and poet Sun Ra and his Arkestra. Deriving its title (as well as the text for its intertitles and chapter headings) from Sun Ra’s poetry and writing collection The Immeasurable Equation, Asili’s film mingles video footage of the contemporary Arkestra (helmed by Marshall Allen since Sun Ra’s death in 1993) with video interviews about Sun Ra, the cosmic potential of jazz and music more generally, and archival sources, most prominently audio of John F. Kennedy detailing the US’ interstellar ambitions.

While much of the video footage is raw, and the use of floating split screens doesn’t always gel, the piece (and its cosmically minded subject, who proclaimed himself to be “an alien from Saturn”) hints at the expansive scope and ambition of Asili’s subsequent work. With this year’s Fluid Frontiers, Asili has concluded a five-part film suite that examines the African diaspora through a series of immeasurable equations: America and abroad (with films shot in Ghana and Ethiopia, as well as Brazil, Jamaica, and Canada); personal and collective history; the past and the present; imaginations and realities; and image and sound. Abandoning digital video for 16mm, Asili has developed his documentary impulse into something more spontaneous and musical, his eye attuned to the unexpected rhythms afforded by montage.

The first film of the series, Forged Ways (2010), collapses Harlem together with Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, and Gondor in Ethiopia. Flora and fauna, as well as clothing and infrastructure, offer some clues as to which setting is which, while other images are ambiguous. Similarly, the editing alternates between the surprising and disjunctive—inviting unexpected comparisons and considerations between images—and the clear and structured, utilizing rhyming shots of boats, pushcarts, and other visual parallels.

Though the footage from all locations tends toward handheld, observational-documentary modes, the New York sequences are loosely structured around a nameless protagonist (played by Julian Rozzell Jr.) and his navigation through the snowy cityscape, as well as wordless sequences in his apartment with a young woman (Kate Wand). Calling to mind La Chinoise (1968) in their colour palette, composition, and choreography, these apartment sequences also evince Asili’s comparably Godardian interest in iconography, in magnitude if not in manner. The filmmaker announces as much early on in the piece when he presents a replica of David Hammons’ African American Flag, which reimagines the Stars and Stripes with the Pan-African red, black, and green, evoking the expansive, imagined collectivity that will become another of the immeasurable equations that run though Asili’s work; later, a decorative assembly of “Hope”-era posters and shirts of Barack Obama in the protagonist’s apartment is cut against murals from across the globe of the former president, pictured alongside Malcolm X and other Black icons.

American Hunger (2013) continues the geography-condensing montage techniques of Forged Ways to conjoin footage shot in Philadelphia and Ocean City, New Jersey (featuring the return of Rozzell from the previous film) with fragments glimpsed in Cape Coast and Accra, Ghana. Extending from its predecessor’s invocation of African American Flag, the film opens with a 1964 quote from Malcolm X urging African Americans to embrace Pan-Africanism and to develop a broader, working unity; it also harks back to the earlier Points on a Space Age in its use of intertitles, one of which hints at both the source of the film’s title by evoking the personal experience (admittedly inaccessible to this writer) of travelling to Africa as an African American: “Since the reasons for travel are often so romantic and incoherent, the traveller often finds himself in a location that only exists in his mind.”

As in Forged Ways and the other works in Asili’s project, in American Hunger the artist captures and cuts across a series of intercontinental street fairs, murals, statues, performances, and portraits, frequently with the subject’s gaze returned directly to the camera; he also introduces some in-camera effects, with sequences of figures walking with slowed, steady footfalls and sped-up footage of dancers in motion. In addition to rich sonic and visual rhythms, American Hunger also introduces moments of quiet contemplation, such as in a sequence shot in the Ghanian holding cells formerly occupied by victims of the transatlantic slave trade.

Borrowing its title from James Baldwin’s essay, Many Thousands Gone (2015) is more contained than any of Asili’s previous films, while still open and deft in its assembly. Shooting in Harlem and Salvador, Brazil—the final city in the Western hemisphere to outlaw slavery—Asili once again presents portraits and performances, while elsewhere incorporating travelling shots from boats and cars and footage of bodies at work, rest, and play. Voiding his film of both voices and narrative elements this time out, Asili also makes use of more traditionally experimental techniques—reel ends and light leaks that occasionally obscure the image, out-of-focus and slow-motion exposures of the Brazilian dancers—as well as a score that was composed live by jazz multi-instrumentalist Joe McPhee, whose spacious, earthy saxophone improvisations both respond to and forge connections within Asili’s footage.

If the first two films in Asili’s project are similar in terms of their hybrid nature, locations, and soundscapes, Kindah (2016) shares the intimate, impressionistic eye of Many Thousands Gone. Again, an experimental score—here a mix drums and wind instruments performed by Asili himself—guides the wordless footage shot in Hudson, New York and Accompong, Jamaica, with accompanying waves and an analogue hum. Footage of rainy streets, a rocky coast, birdcages, and sparse buildings is paired with a sunny parade and celebration that was shot at the base of the ancient, immense Kindah Tree in Accompong, an historic site of Black liberation where former slaves from the Ashanti, Congolese, and Coromante tribes came together in 1739 to fight for, and win, their autonomy from the British governor. While the film is thus grounded in history, the style is observational and impressionistic rather than didactic; it is history as viewed from the present day, whether in the form of celebration or contemplation.

In addition to his work as a filmmaker and a teacher at Bard College, Asili has a sideline in DJing, so it is perhaps unsurprising that music and sound are often as foundational to his works as the images. Largely eschewing sync sound in the series outside the narrative sequences (and even here, not all such sequences include spoken dialogue), Asili more often incorporates and assembles music, spoken-word excerpts, and other ambient recordings, resulting in soundtracks that are frequently disconnected from the image even as they help to bridge the temporal and geographic gaps between the disparate footage.

The predominantly sync-sound readings in Fluid Frontiers thus represent something of a stylistic shift for Asili, and lend the final film in his quintet a new immediacy, a here-and-nowness. Shot in Detroit and Windsor, Ontario, on the Canadian side of the Detroit River, the film features the most geographically proximate of any of the locales in Asili’s films, while inviting the viewer to consider the profound distance that once lay between them—specifically, the distance between slavery and freedom, as the region was a vital terminus for the Underground Railroad in the 19th century. (The title of the film is again borrowed from a scholarly history, a collection of essays about the Railroad, dangerous border crossings, and Black settlements in the Detroit-Windsor region.)

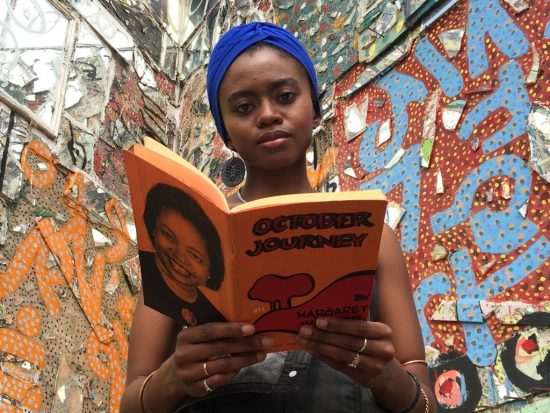

Performance and portraiture are once again present as two of the artist’s ongoing visual concerns, which he here weds via a series of musical performances and spontaneous, unrehearsed readings of poems by Sonia Sanchez, Audre Lorde, Etheridge Knight, Margaret Walker, and others, captured in single, static takes. Recited from original publications produced and printed in the late ’60s and ’70s by Detroit’s Broadside Press (one of several historic independent Black presses that emerged in the Detroit area), many of the chosen texts retain a startling relevance—perhaps none more so than Dudley Randall’s “Ballad of Birmingham,” a pained response to anti-Black domestic terror.) Between readings, Asili incorporates mostly static images of buildings and sculptures, accompanied by a vintage recording of another Margaret Walker poem, “Harriet Tubman,” read by the poet herself in 1975, with Asili’s haunting, sparsely deployed organ carrying and amplifying the words.

More so than any of Asili’s other films, in Fluid Frontiers the demarcation between the American and Canadian footage is frequently indistinguishable, particularly during several of the direct-address readings, which are set against nondescript walls and trees. The device serves to provoke questions of similarity and difference both across time and across borders, inviting us to examine how much has really changed in present-day America, and to what extent Canada is “Keeping the Flame of Freedom Alive,” to borrow the engraving from Windsor’s Tower of Freedom, which looms over one of Asili’s readers. The Tower is one of the readily identifiable buildings and landmarks that do ground the film’s spaces geographically, as does a Windsor-side view of Detroit’s immense Renaissance Center; on the other side of the river, Asili grants us sights of the Dabls African Bead Gallery and Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project, a large-scale outdoor neighbourhood-meets-sculpture garden on Detroit’s east side which has stood for over 30 years, despite recurring threats of destruction.

While not especially dense, the live and recorded readings fill the majority of the film’s soundscape. One notable exception arrives at the film’s midpoint, which cuts to an extended, fixed shot of a crimson setting sun, shot across the Detroit River and framed by the international Ambassador Bridge. The peaceful churn of the water occupies over half of the frame, and the audio track is reduced to ambient sound of wind, waves, and distant offscreen motors, before a cut to a tableau of nondescript tombstones. The sequence offers a moment of purely visual poetry—of “languidity,” to return to Sun Ra—that complements the written and spoken poetry that structures the rest of the film.

This moment of pause also serves as a subtle eulogy to the late Peter Hutton (a former colleague of Asili’s at Bard), the one-time seaman and self-described “Hudson River Filmmaker” who made water a constant theme and subject in his work. Water is a prominent presence is Asili’s cycle as well, though for almost of the series it bound by or seen from a shoreline, whether a coast or the bank of the river. The sole exception is the final shot of Many Thousands Gone, wherein a frothy wake traces the tumultuous impression of a boat’s passing on the water’s surface. Whether a fluid frontier, an immeasurable equation, or an “unresolved unfolding” (to borrow a phrase from theorist Christina Sharpe), this is only one of numerous moments in Asili’s work where an unseen movement between two points marks its landscape, and forces us to read it anew.

Jesse Cumming