Odd Couple: The Future

By Nick Pinkerton

The Future is narrated by a foundling feral cat, visible mostly as an expressive pair of forepaws, one bandaged, waiting impatiently at the animal shelter to be picked up and taken home by the couple who rescued and named it. Paw-Paw’s crinkly voice—provided by writer-director Miranda July—returns throughout like a chorus, suggesting a child waiting to be born in its mounting anticipation. Most of The Future is, however, spent with Paw-Paw’s prospective “parents,” Sophie (July) and Jason (Hamish Linklater). They are thirty-five, childless, living in a shoebox apartment somewhere in Los Angeles. He does over-the-phone tech support, she works at a children’s dance studio in a Creative Movement-type class.

Sophie and Jason are introduced on the sofa together, legs interlocked, on identical Mac laptops, hair in identical brown ringlets. One might almost think July has taken on a double role. In the classic comic duo, a la Mutt and Jeff, the visual impact comes from contrast; the joke here is the uniformity, a microcosmic example of the attraction of like-to-like playing out in their presumable neighborhood (Echo Park? Silver Lake?). And Sophie and Jason are a comic duo, evident immediately from their rapport, a routine in both senses of the word, riffing about their fantasy superpowers in a jokey interplay that’s worn well past laughter.

The month-long wait before they can bring home their sick cat becomes a reprieve, time for a grave self-assessment. Anxious at the impending responsibility and their mutual lack of professional accomplishment, Sophie and Jason decide to treat the days ahead as their “last month ever,” quitting jobs, cutting off the internet. Opening himself up to following the whim of the world’s obscure signs and signals, Jason impulsively winds up going door-to-door on a tree-planting initiative, though when Sophie skeptically questions him about his new environmentalism the best he can offer is “I’m glad the outside’s there.” Sophie institutes a “30 Days, 30 Dances” YouTube project, and immediately spooks herself into creative paralysis. Jason answers an advertisement for a hair dryer in the PennySaver classifieds and becomes friendly with the old man (Joe Putterlik) who placed it, and whose private museum of naughty holiday cards that he’s made his wife since 1948 is a curiously touching monument to fidelity. Sophie is happy to find her own escape from eerie domestic symbiosis in phone conversations with a divorced, middle-aged father, Marshall (David Warshofsky), living in exotic suburban Tarzana. This leads to more than talking—just knowing the outside’s there isn’t enough.

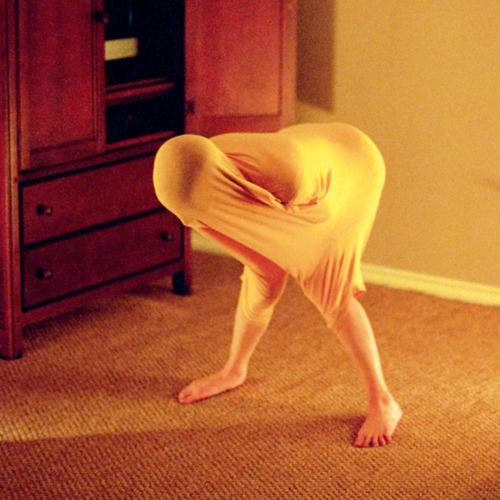

“Intimacy” is allegedly the overarching theme of July’s work. I cannot vouch for this fact, having previously avoided that work under the assumption—incorrect, as it happens—that I would hate it. Be that as it may, there are certainly binary images which recur throughout The Future: indoors and outdoors, day and night, all abstractly referring to the push-pull of homebody comfort and stray adventure. At first these symbols are worked into the dialogue, but then, at a crucial bend in Sophie and Jason’s relationship, a film which has only been touched by wisps of fancy leaves realism behind entirely. Jason turns to the moon for advice; the moon answers with Putternik’s voice; Sophie begins a new (parallel?) life with pleated khakis-type Marshall, but is stalked by a crawling security-blanket shirt bearing the motto “C’est la nuit,” which creeps after her like an unpaid debt. When it finally catches up, Sophie slides her slender legs through the shirt’s armholes, bags her head and torso in the rest, and commences to dance to Beach House’s hypnotic “Master of None,” looking something like a plucked Perdue chicken.

This may be taken as a cop-out at the emotional centre of the movie, July retreating into oddball gallery-art vagaries when faced with emotional depths that her pop-eyed, porcelain, Olive Oyl screen presence might crack under. But the Young Psychodramatists Association of America is by no means lacking for membership: July’s gambit is exhilarating precisely because it passes by the tempting cul-de-sac of whatever currently constitutes dramatic realism, instead seeking out a poetic logic compatible with the emotional logic and history of her characters. Earlier in the film, Jason makes a glancing reference to the stalking garment, nicknamed “Shirtie,” and its reappearance brings a whole slew of associations to mind. Its shapeless, laundry day comfort suggests the slack surrender of home (Sophie’s musings seem to hover around a dream of just not having to try anymore). The dance? It could be an inside joke between live-in lovers together long enough to be weird with one another—or something else entirely.

The material feels homespun, the casting keen and professional. Though July is generally associated with marginal traditions like esoteric performance art and cozy K Records pop, there’s more than a smidge of (good) Neil Simon in her dialogue, which accounts for her crossover appeal. When, under pressure to do last-minute “essential” Googling before the internet goes out, Jason can only come out with “Christmas falls on a Tuesday this year.” Elsewhere, he defines life left after fifty as “loose change”: “Not enough to get what you really want.” Marshall and Sophie have a post-coital exchange, perfectly handled, on how to carry on an affair: “Traditionally, people either tell the truth or they lie.” “Jason and I are very close. I could never do either… of those things.”

How we respond to narratives is, to a point, determined by the degree to which their characters make agreeable or at least compelling company. The Future, then, won’t find favour with viewers for whom adults emotionally daunted by adopting a cat are ridiculous, beyond the pale, not worthy to be dignified by drama. That premise seems to me no more ridiculous than, say, Laurel and Hardy opening an appliance store in Tit for Tat (1935): each concerns slightly absurd but recognizably human figures confounded by everyday responsibilities. Reinforcing the crucial presence of the present, The Future is a bittersweet reprimand for what Sophie and Jason leave undone. It is a measure of its achievement that we leave with a sense of the lack.

Nick Pinkerton