TIFF 2013 Postscript | Wavelengths 2: Now & Then

By Samuel La France

“There is no post-production in my work,” claims Helga Fanderl in an expository video posted on her website. Fanderl’s statement reinforces the spontaneity and immediacy of her shooting methods, the results marked by an explicit sensitivity toward the objects, gestures and spaces that she films. And while it’s true that her films are edited in-camera and are processed with little or no manipulation, Fanderl revealed to the audience at the second shorts programme at Wavelengths 2013 that there is in fact an element of assembly to her practice. For every screening, the artist selects a few of her single-reel films, and “programs” them as a unique piece that she refers to as “composed unities”: in this case, a cinematic septet entitled Konstellationen [Constellations] that included glimpses of a pacing leopard, an autumnal chore, and a Rotterdam river. These collections of images become recollection images, their endless continuities and associations working together to narrow the temporal gaps that separate the “now” of perception from the “then” of memory.

Navigating similarly tricky terrain, Hannus Schüpbach’s Instants begins, appropriately, with two still images: one of foliage in the wooded regions near Séguret and Vaucluse where the film was shot; and another of a young girl, the daughter of archaeologist and poet Joël-Claude Meffre, captured in mid-air at the apex of an impressive leap. The sequence of images of Meffre and the surrounding woods that follows suggests an attempt by the poet (or the filmmaker, or both) to record visual and tactile memories of this environment, and to encode said memories with personal significance. It seems easy enough at first, as Schüpbach presents us with an image of a hand delicately palming a stream’s running water, followed by a shot of the same spring tinted blue that suggests that a mnemonic impression has successfully imbedded itself. The poet’s hand is later shown scribbling neat cursive into a notebook; as the film progresses, the camera’s lens and the poet’s pen both busy themselves with the task of capturing increasingly elaborate instants. It seems that Schüpbach understands very well the preparatory and repetitive cognitive functions that the mind must execute to map out memories; it takes persistence to capture these fleeting moments in that permanent blue stillness, a fact made clear by a succession of moving-image glimpses of Meffre’s daughter suspended in the air. But the hard work pays off, as the concurrence of image, text, mind, and environment reinforces the collaborative nature of these varied acts of making.

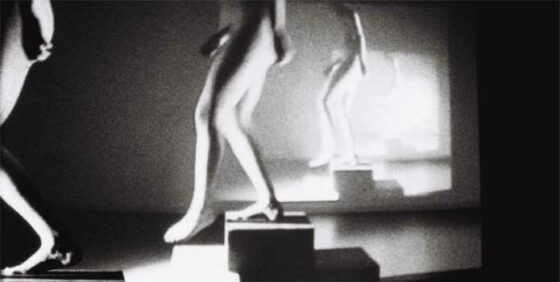

An exercise in collaboration of another kind, Homme en mouvement, 2012 (co-directed by Christophe M. Saver, Ruben Glauser, and Max Idje) is the product of an assignment given to the filmmakers by the aforementioned Mr. Schüpbach. A twenty-first-century update on Muybridge and Marey, this brief study of a man repeatedly walking up and down a two-tiered podium is recorded by a digital camera whose images are simultaneously projected three-fold on the wall behind the subject. The synchronicity of the man’s looped strolling and the video replicas that serve as a backdrop is disrupted by the movement of the 16mm camera that produces the film’s master frame, which tracks left and right and back again. The film is concise, both in terms of runtime and formal execution, but it’s also a delightful reconciliation of two mediums that are too often placed in opposition to one another.

Another proponent of the collaborative potential of celluloid and pixel, Toronto-based filmmaker Stephen Broomer has relied on digital video as an intermediary means to realize a series of beautiful, densely layered 16mm films. Adopting a radical shift in technique, Broomer’s newest video Pepper’s Ghost eschews film altogether in an effort to create equally spectacular superimpositions with as little technical mediation as possible. Using a DSLR to record both sides of a two-way mirror that separates his office into two distinct spaces, Broomer and two collaborators (Eva Kolcze and Cameron Moneo) manipulate our perception of this environment by taping colour gel filters onto the mirror, hanging patterned fabrics, raising and lowering the window shades, and turning each room’s lights up/down/on/off. Broomer makes no effort to mask the simplicity of his methods, nor the three bodies at work, suffusing the piece with a “what you see is what you get” ethos that yields a mesmerizing collaborative self-portrait. This reflexive chamber piece is accompanied by field recordings of Buddhist chants circa 1972, imbuing the work with a meditative tone that Broomer links to a desire to engage with the psychic history of the space, which was previously used as a site for psychological observation (hence the two-way mirror). All the more compelling and no less pleasing to the eye, Broomer’s decision to unravel his images instead of stacking them atop one another reveals the recursive nature behind this deceptively banal space.

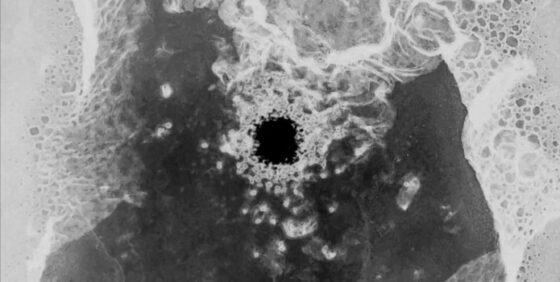

If there is a line to be drawn through these works, the necessary outlier of the programme may be Nakao Tasaka’s Flower, a mind-blowing multi-format piece that plumbs the depths of hunger by tracing it down to a cellular level. A narrator tells us a story of a famished bear that gobbled up members of his family in a desperate but unsuccessful attempt to quell his insatiable appetite. The images that accompany this fable are etched or drawn cellular forms, sliding and splitting across the frame and gradually multiplying into incredibly complex grids; also in the mix are shots of a misty waterfall and, deviating from the film’s predominantly black-and-white palette, an underwater angle of catkins floating and fluttering like prisms at the water’s surface. I’ve read this programme as a meditation on how teamwork of various kinds can be an effective tool in bridging lived experience and recollection; Flower, with its darn-near impenetrable network of grids and textures, might not fit into that rubric so neatly. If Chris Marker once asked “How can one remember thirst?”, Tasaka asks “How can one forget hunger?”

Samuel La France